I am a 40-year-old man who still plays video games. I say that (both parts of that, actually) with a not-insignificant amount of shame. I know I thought, at several points in my adult life, that I should probably give them up, but then I also discovered a level of disposable income, occasional free time when my kids are with their mom, and that I live in Iowa, where nothing more worthwhile ever happens. Of the games I play, Out of the Park Baseball (OK, it’s more of a sim than a video game, but still) has taken up far too much of my time and attention lately in a way that Diamond Mind Baseball used to before I switched to a Mac.

I say these things to you not to engender your sympathy or your scorn, but to bring up an interesting byproduct of current baseball strategy. We have all noticed teams using the “Opener Gambit,” as I’m calling it, because it sounds cooler than “Opener Strategy” or “Using an Opener,” which sound respectively like a way to pick up someone in a bar and how I get the cap off a beer from a brewer who thinks they’re too fancy for a twist off.

You know the particulars: A reliever starts off the game to handle, usually, the first two innings before giving way to a “primary pitcher” or a “long reliever” or a…do we have a cool term for this yet? I haven’t seen one I like… Anyway, the “Opener” gives way to the next guy, who (in theory) faces the opposing lineup two full times, and maybe faces the 7-9 batters a third time if things are going well.

It’s a strategy—sorry, gambit—that’s seen mixed results. Like Gonzo leaping in front of a taxi in The Great Muppet Caper, it’s great when it works. But it’s awful when your Opener isn’t on and Gabriel Moya gives up two runs in the first inning before giving way to an ineffective Zack Littel and suddenly you’ve given up 18 runs and Chris Gimenez is pitching again. Then, it draws attention to itself and you get to hear the curmudgeonly complaints of whatever your local equivalent is of Bert Blyleven until you turn off the real game in frustration and turn your attention back to your now-overheating laptop and the fictional baseball team you’ve built for yourself that’s currently leading the AL Central because you have turned the AI down.

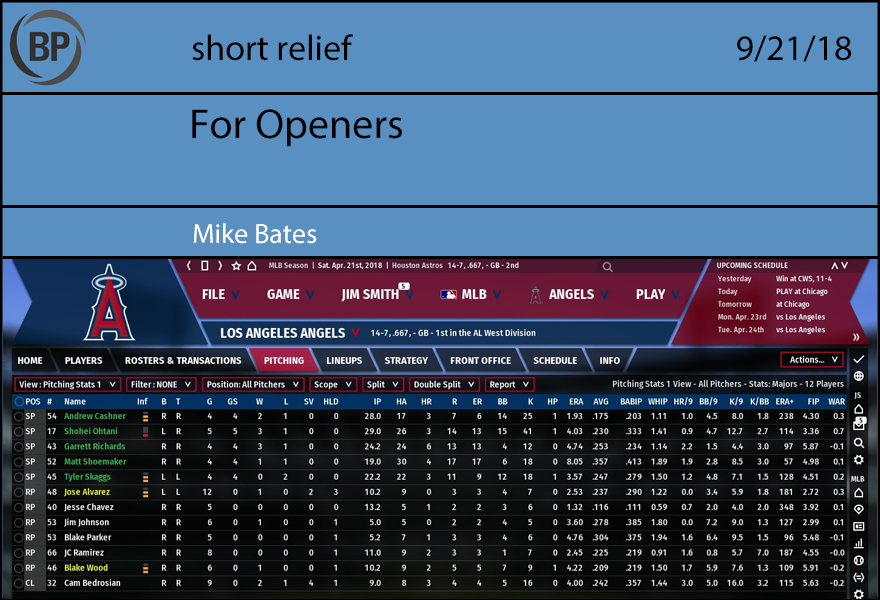

Which brings me to my point, which is: The ratings for starting pitchers and relievers in these games are going to be F’d up the A, you guys.

Christian Yelich became the second person to hit for the cycle this season … last month. Both were against the Reds, and he’s in the history books for getting all four types of base hits against the same baseball squadron in the same calendar month, something all the actuaries missed. He also had six hits in the game, so he was far from shy of the cycle. He was by far proud of the cycle.

Cycle-based emotion always seems to derive from shyness, or so we think. It’s the most common one. Being shy of the cycle, of course, means that you have just three of the requisite hit types, but nobody talks about being:

Aloof of the cycle: You got two different types of hits, but whatever.

Nervous of the cycle: Getting one of the hits needed in the game but not the other three. Also see: “getting a hit in a baseball game.”

Pensive of the cycle: You needed a single for the cycle, and got it, but thought about stretching it into a double, and got thrown out for thinking too long.

Confused of the cycle: Telling your grandchildren that 40 years ago you got a cycle but instead you were thinking of the night that you got a double, a walk, a catcher’s interference and, um, what was that other one.

Self-doubtful of the cycle: Getting a home run and then a triple (the two hardest ones!) then mid-game checking social media to see if people think you will finish it.

Embarassed of the cycle: You recorded a cycle, and the last one you hit was the home run, and during the trot your pants fall down.

Disappointed of the cycle: When your mother asks you to hit for the cycle but you don’t.

Disdainful of the cycle: Either (a) getting four hits that total more bases than what a cycle is worth without actually getting a cycle, or (b) penning a column against the cycle in the New York Times.

Surprised of the cycle: Hitting for the cycle as a member of the Detroit Tigers.

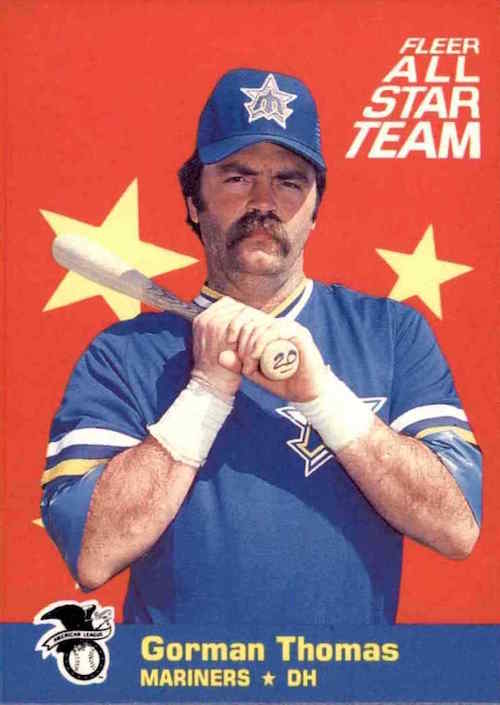

You’ve done something wrong. I don’t care what it was: Maybe you grazed a couple of yogurt pretzels out of the bulk tub at the supermarket, or you jumped ahead of your turn at a four-way stop, or your thoughtlessness made a teenager feel insecure about the identity they’ve submitted to the world. It doesn’t matter. It turns out that the punishment for all those are the same: you’ve been condemned to take a look at this shitty 1986 baseball card.

Stare at it, you criminal. Gaze at the wristbands, which look like the starting equipment on a last-generation console RPG. The various necks, strewn akimbo. The mesh-backed cap, $12 at JC Penney’s, the brim bent out of shape by some bullying eighth-grader. The asymmetrical half-trapezoidal All-Star Team logo, laid in perspective against the flat, tomato-red background, the cardboard so thin that you can see the text on the back shine through when you hold it up to the light. The lazy, garish Soviet yellow stars, shaped and scattered like a toddler’s attempt at sugar cookies. The American League logo that no one has ever, in 1986 or today, cared about. The pullover jersey, stitched just on the cusp of the moment when baseball players realized they didn’t want to look exactly like the fans. The eyes, and their tired, cruel glare. The eyes of a man who is thinking about wings: the wings he’d like to have, the wings he had last time that were kind of a letdown, how much shit he has to go through before he gets more wings.

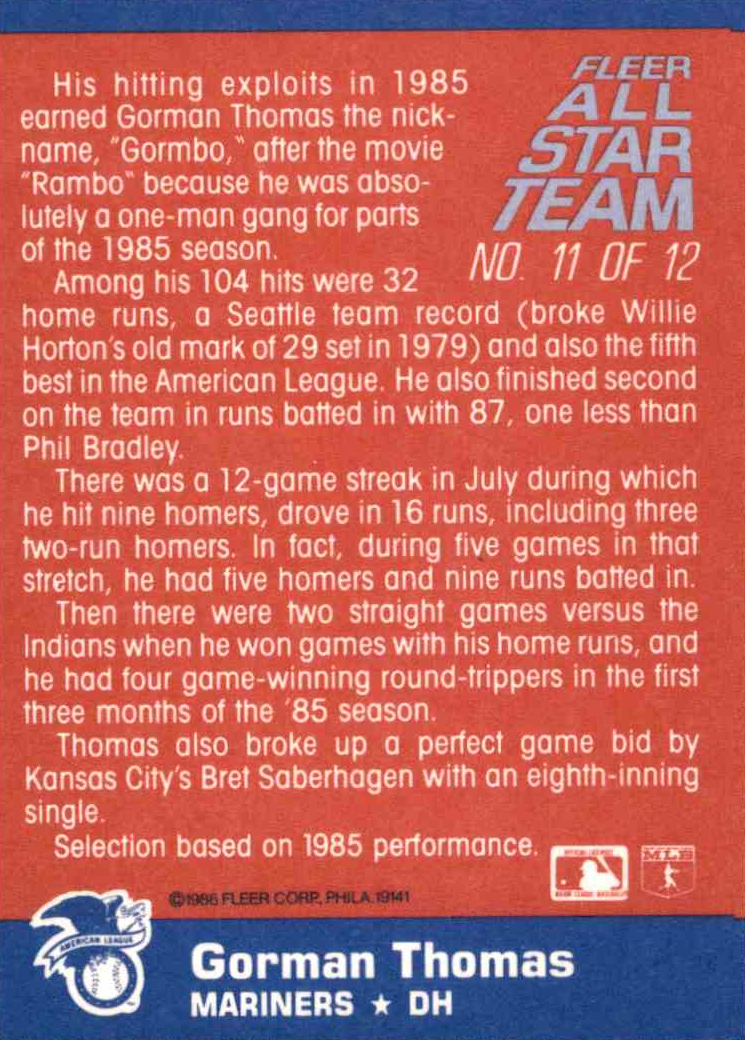

Now flip the card over:

Take in the reliance on old-school statistics, which in 1986 is fine by itself, except for the pains the card takes to avoid mentioning his equally of-its-time .215 batting average or his 10th-worst 126 strikeouts. The cherry-picking streaks. That final line, thrown in as a weak disclaimer against favoritism. The “Gormbo” nickname, which no one ever called him except the poor college intern at the Fleer company, his body trembling from the caffeine and the hopelessness, digging through a dog-eared Bill James Abstract looking for something good to say about Gorman Thomas.

But most of all: The fact that this was an insert card, a rare, one-in-eight packs deal, and you could see that tomato red edge as you pulled apart the wax and think, did I get a Don Mattingly or a Cal Ripken? No. You got a Gorman Thomas card. You have touched this card, and its evils have absorbed into your skin and forever linked you to its invisible mediocrity. A piece of cardboard so accursed that if you gave someone a paper cut with its edge, the wound would never heal. A generation was laid to waste, or at least one out of eight, by the Fleer Gum Corporation as they declared: this is how it will be, children. This is your adulthood. Even the wings will disappoint you.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now