Three Metaphors Outside Orlando, Florida

By: Jason Wojciechowski

By Monday at 8pm Eastern time, any player not on a 40-man roster would be available in the Rule 5 draft that will take place in a few weeks at the Winter Meetings. It was, therefore, a fast-and-furious day of additions and subtractions; you probably know intimately about your team’s moves, and you probably know extraordinarily little about any other team’s moves because they are, for the most part, about touching up around the edges. Instead of talking about the transactions themselves, then, let’s create three metaphors for what it means to be added to the 40-man roster on November 20.

Middle-school graduation

You’ve got to do this if you want to graduate high school, and you do make more money as a middle-school graduate than you do if you’ve left school before that point, but generally speaking this is a stepping stone on the way to your actual goal. It involves a ninety-minute assembly with people walking onstage to get awards, a poorly-edited video montage, and a tinny loudspeaker rendition of Vanessa Williams’ Save the Best for Last. You’ll probably get kudos from your Uncle/Aunt Terry, but even you won’t be all that jazzed, and they don’t give you an envelope of cash along with the hug. On top of all that, things get a lot harder next year: you’re in big-kid school now, and it’s time to live up to those standards.

Promotion to Regional Sales Manager

You’ve been a Regional Sales Associate for six years. You’ve learned your company’s business and their products, you’ve made contacts, you’ve gained experience and a certain savvy. Now, the big day: Regional Sales Manager … joining about 100 others across the country with the same title. And that’s just in your company. Four of your high-school friends are also Regional Sales Managers. You’re making more money, but your mom doesn’t actually respect you any more than she did yesterday. She respects you a lot! But not more than yesterday. When her friends ask her what you’re up to, yesterday she told them, “She sells ____s.” Today she tells them, “She sells ____s.”

1550 on the SAT

Congrats: You are objectively in the top 1 percent of all SAT takers in the country. It is meaningless; you should have spent the time you used studying to volunteer at the local homeless shelter instead. Or worked on your video-editing skills.

The Scorecard

By: Matt Ellis

It is the middle of the 19th century. The history of thought has moved through Kant to Nietzsche and the American pragmatists. For the first time in history, a particularly modern understanding of a secondary order of representation has presented, a regime of signification that tells us something fundamental about our relation to the world.

We all know what baseball looks like today, sounds like–we could map it on a game board or open the At Bat app on our phones: you can represent an AB through a graphic strike zone with green and red dots, or you could draw some lines with bounces where the ball hits from 4-6-3 or something along these lines. But I proffer a different theory: that for the first time in history, in the middle of the 19th century, with the arrival of the scorecard: abstraction became a metric through which one could translate experience.

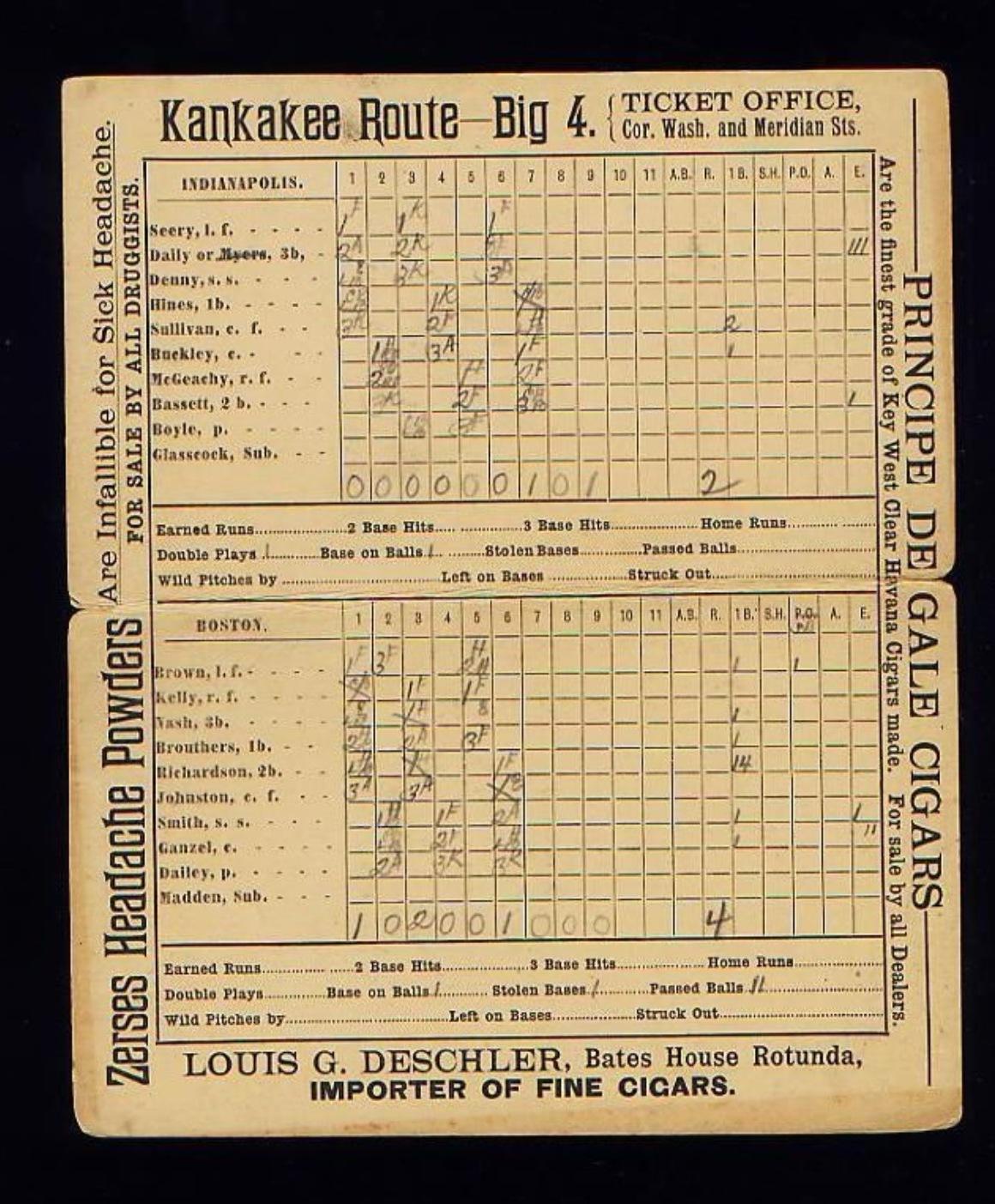

This is, as we all know, a scorecard. In particular, it is a scorecard from 1889, featuring many of the same symbols which your favorite sportscaster currently uses to delineate the events of each game: doubles, force-outs, strikeouts. And note the advertisements (capitalism never sleeps!).

But did you ever stop to ask how it was possible that at a certain moment, historical human action was intelligible through a semiotic system in which actions were representable through symbols that carried with them the entire content of the idea able to be translated? If, as we heard, early baseball featured urban areas filled with local strongmen and miners or whatever throwing around the rawhide ball, it is undeniable that the lure of the game spread out into rural America through the same timeline. But how was it that a “1F” and a “3A” turned into a symbolic system allowing spectators to understand the rules of the game without ever seeing the Boston Beaneaters play in person at all?

The entire history of American/Western philosophy, at this moment in time, begins to give weight to symbolic systems of representation following the Kantian revolution–the subject/object divide, perception, knowledge, experience. What if the very emergence of baseball as a normative game with inputs and outputs prescribes a certain mode of Being In The World which allows us to represent action through signs, a particularly Nineteenth Century game that is utterly imbricated with that early modern global order? What does this mean for the evolution of televisual norms, cell phones and apps, tabletop games a century later?

The history of baseball is long-disputed terrain. John Thorn argues the game traces not only back to early British bat and ball games but also into the late Sixteenth Century with a famous woodcut poem about a ball breaking a window. All of these things are true, but I wonder if the more profound realization is left to the books: that baseball existed before democracy, before The New World.

But Baseball as such couldn’t take its modern form until the day in which abstraction and symbolic representation became thinkable in intellectual life, in journalism, philosophy, popular culture. If this is right–if the game itself requires a level of mediation, then we are left with a fundamentally new understanding of the nature of the game, and its position in global history.

In this sense, it is not only as Ken Burns tells us–a haunted game–but it is rather a particularly modern game, one which reaches back into the past but nevertheless is structured by the very same global order that we currently inhabit. A metaphor, embodied. Try explaining it otherwise.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now