Early this offseason, it looked like Alex Cobb could find a new home very quickly and get very rich in the process. Rumors tied him closely to the Cubs, for whom his former manager and pitching coach both work, but Cobb also had a handful of other suitors, and his reported asking price quickly shot up to something like four years and $80 million. Then, as so often happens when a free agent catches some early helium but sees the moment pass without signing, countervailing reports nudged Cobb back out into the middle of free agency’s open water.

The offers he was rumored to be mulling grew steadily less appealing. In those waters has he bobbed ever since, and the tide has turned against him. If Cobb is to get any kind of life preserver now, it won’t come in the form of generous projections. Our PECOTA projection for him won’t make any general manager’s socks roll up and down. In fact, despite the clear hierarchy that has developed in the starting pitching market (Yu Darvish and Jake Arrieta in some ill-defined top tier, then Cobb a step lower, and Lance Lynn somewhere below Cobb), PECOTA would have us slot Cobb in below Lynn, far below the top free agents.

| Pitcher | Innings | ERA | DRA | WARP |

| Jake Arrieta | 147 | 3.69 | 4.09 | 2.6 |

| Yu Darvish | 155 | 3.60 | 4.15 | 2.5 |

| Lance Lynn | 121 | 4.47 | 4.99 | 0.8 |

| Alex Cobb | 128 | 4.92 | 5.45 | 0.4 |

Those all feel like conservative estimates for innings, although then again, three of these four pitchers have had Tommy John surgery within the last two seasons. What really stands out is the gap in expected performance, on a rate basis.

For Lynn, that comes as no huge surprise to me. I wrote about my unbelief in him earlier this winter. Cobb, however, doesn’t seem to deserve this. In his last three full seasons, he’s been worth 3.0, 4.6, and 4.4 WARP. He’s had better-than-average cFIP marks in all five seasons during which he’s made six or more starts. In those five seasons, his worst DRA- was 87, in 2017.

Of course, DRA- is a holistic expression of what a pitcher contributed to his team, based on the way all of his skills converged and complemented one another in a given sample, and cFIP is a measurement of the true talent the pitcher demonstrated in the process—still holistic, but emphasizing the things the pitcher controls most. When PECOTA goes in to do the difficult work of predicting a pitcher’s future, it doesn’t just take these holistic metrics, average them, apply an aging curve, and flip them forward. The system deconstructs its subjects much more than that, and when one breaks down Cobb’s whole package into its component parts, it becomes a little easier to see how pessimism could creep in.

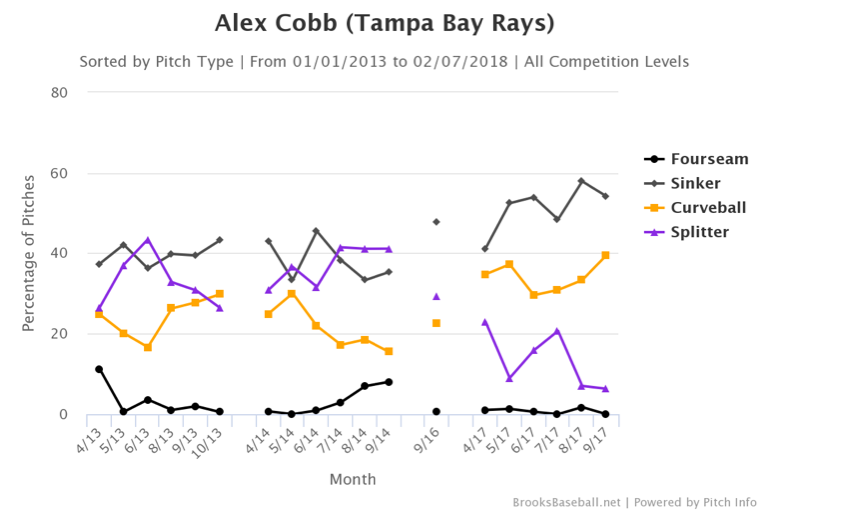

Put another way: it’s pretty hard to see how Cobb’s parts can be put back together to form a total package as formidable as he has been. For one thing, Cobb has been something close to a two-pitch pitcher for most of the season-plus since his return from elbow surgery. He’s always used an unusual sinker-curveball mix, but both pitches used to complement and set up his true out-maker, the splitter. Since shredding his UCL, he’s roughly halved his use of that devastating offering, and while it might have allowed him to survive his fullest season to date, it also made him something less than his optimal self.

PECOTA doesn’t directly see this change in repertoire; its code doesn’t include granular, scouting-level detail like that. It sees it indirectly, though, because without that changeup, Cobb is unable to miss bats or induce ground balls with the same consistency.

| Season | O-Swing% | Contact% | GB% |

| 2013 | 34.3 | 77.6 | 57 |

| 2014 | 34.3 | 74.1 | 56 |

| 2016 | 28.8 | 82.5 | 52 |

| 2017 | 29.3 | 82.9 | 49 |

Without his splitter, Cobb induces opponents to expand their zone at a lower rate. He gets whiffs less often, when they do swing, and when they do make contact it’s not on the ground as often as it was when he was throwing The Thing. These are all things PECOTA can see perfectly well, and they’re major reasons for his ungenerous projection. If one believes that Cobb will regain full confidence and feel for that pitch as the scar on his elbow gets older, one can reasonably conclude that PECOTA is underrating Cobb.

Of course, that’s an awfully kind expectation, and avoiding that kind of magical thinking is one good reason to look to a projection system in the first place. PECOTA uses comparable players to inform its projections, and in the case of a pitcher like Cobb, examining those comps can augment our understanding of the projection the system ultimately produces. Many of the top pitchers on the list of Cobb comps are guys who, like Cobb, were largely good but injury-prone throughout their 20s. (Cobb is 30, so the system looked for and returned pitchers with similar career arcs through age 29.)

Here are Cobb’s top 30 comps, listed from highest similarity score downward (read down each column, then move to the next):

That’s a long list of pitchers, but the seasoned eye will find many guys whose long injury histories turned in the wrong direction right about when they hit 30. Just five names down the first column, we already find three hurlers who signed huge deals that their teams have regretted almost since the day they were signed. Guys with this profile—good, but not an ace, and not durable—don’t generally age well at all.

Then again, there are some success stories in here. More importantly, maybe the specific point at which we happen to be evaluating Cobb (and at which he happens to have hit the open market) is distorting the truth about him. After all, he just pitched a career-high 179 innings, and doesn’t have a massive number of innings on his arm from earlier in his career. He was good in 2017, too, as we documented above. His cFIP was 98.

Of those 30 comparable pitchers, only six pitched as many as 150 innings and had a cFIP better than 100 in their age-29 seasons. Here they are, and I’m adding one more column to the table.

| Player | Season | Innings | cFIP | Command Score |

| Zack Greinke | 2013 | 178 | 92 | 56 |

| Gio Gonzalez | 2015 | 176 | 92 | 68 |

| Ubaldo Jimenez | 2013 | 183 | 91 | 50 |

| John Lackey | 2008 | 163 | 93 | 47 |

| Anibal Sanchez | 2013 | 182 | 72 | 37 |

| Matt Garza | 2013 | 155 | 93 | 58 |

That figure on the far right is Command Score, a new rating introduced during Pitching Week here at BP. It scores how often and how finely a pitcher is able to work to the areas of the zone that most favor them—that make life toughest on opposing batters because of their inability to drive pitches thrown there and because pitches taken in those areas tend to be called strikes. A perfect score is 100. Cobb’s 2017 mark was 63, good for ninth-best among the 75 pitchers who threw at least 150 innings.

With pitchers whose career arcs (and especially health records) are similar to Cobb’s, it seems likely that command becomes a requirement for sustained success. Many of these guys lose velocity, even faster than their healthier peers. Cobb is among those who throw about as hard as ever into their 30s, but like some of them, he’s lost something else: the aforementioned elite out pitch, the changeup. When things upon which a pitcher usually relies desert them, only the ones with good feel for their release point, some deception, and the feel for pitching to start reshaping or adding and subtracting on pitches, find new ways to thrive.

Command (the statistic) doesn’t perfectly measure command (the skill), of course. Nor is it universally true that pitchers with good Command (or command) age better than others. Looking at the six guys to whom Cobb’s most recent season best compares, though, it’s at least encouraging to note that he seems most similar to Zack Greinke and Gio Gonzalez—not only in PECOTA’s eyes, but based on the innings, cFIP, and Command Score they each posted in the season in question.

If one can find a reason to hope that Cobb will be a true three-weapon guy again, and if one accepts that there’s some reading of the PECOTA comparables that doesn’t condemn Cobb the way the final output does, then this last point is easy to accept. It’s straightforward and easy to explain, though hard to quantify. Here it is: PECOTA simply isn’t equipped to properly project a pitcher who missed all but a handful of starts over a two-season stretch within the last three years. It’s reacting a lot to that lack of data, and maybe even to the ugliness of the few numbers Cobb did post late in 2016.

It’s penalizing him for that, and it’s not weighing the good seasons he had in 2013 and 2014 anywhere close to as heavily as a human would (and probably rightfully would, given what else we know about Cobb and given the way he bounced back in 2017). It’s seeing a pitcher who has already moved into a sharp decline phase. That can’t be ruled out, per se, but it’s not what the balance of evidence suggests about Cobb. It’s a bit extreme—the rare case in which an algorithm designed to be conservative and to take the long view has been baited into swinging too far in one direction.

Now. we shouldn’t dismiss what PECOTA is saying about Cobb, especially as it relates to the way his market has unfolded. The actuarial nature of the algorithm does a good job expressing (if only implicitly) the risk Cobb presents, and that risk is likely being considered by every front office pondering a pursuit, even as we on the outside tend to explain some of that risk away. The system is probably at least somewhat wrong about Cobb: it’s not at all likely that he turns into a pumpkin overnight, even though that’s exactly what happened to his top comparable pitcher.

It’s right enough, however, to give everyone pause, and while Cobb was never in line for a contract the size of those signed by Jordan Zimmermann, Matt Cain, and Homer Bailey in recent years, this sketch of him might make teams wary of giving him even an inflation-adjusted version of the deals that went to Ubaldo Jimenez, Anibal Sanchez, and Matt Garza.

Cobb’s projections are so bad that, if he were to sign with the Brewers, Twins, Angels, or Mariners, he would slot in as their fifth starter, and if he signed with the Cubs, he could actually make them as much as one win worse, in the eyes of PECOTA. As wrong as that feels (and as wrong as it almost certainly is), the small kernel of truth at its center is what’s kept Cobb on the market this long, and what will keep him from making the kind of money for which he hoped in November.

To celebrate the launch of the 2018 PECOTA projections, we’re offering 18% off new subscriptions and extensions of existing subscriptions. To take advantage of the limited-time offer, pick a subscription and enter the discount code “PECOTA18” at checkout.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now