There’s a video circulating of a young man striking out his best friend to win a high school championship game, then skipping his team’s celebration to hug and console his buddy. This footage has inspired the nation to rise up as one and say, “Love is a part of baseball.” What I’m here to tell you, with decades of both expertise and smelling like a hot dog to draw from, is that it isn’t.

Now, you might not be able to tell from my soiled, untucked uniform shirt and my clearly-a-child’s-medium pants, but I’ve experienced a lot of friendship in my life. I’m quite popular around the park. When I approach young families, they toss food to me and laugh and take pictures while I feverishly consume it with both hands. So I know what it’s like to be loved.

But this behavior following the last pitch of a championship game is inexcusable. Striking out your best friend to win it all is the coolest thing you can do in sports. I once had an 0-2 count on my half-brother and chose to hit him in the ear with a pitch, even though there were two outs and I was finally, finally going to beat him as part of a summer-long backyard wiffle ball-thunderdome I forced him to play with me because I kept losing. Instead, I chose to try and hurt him physically, and you know what? He’s a successful real estate mogul now who can definitely hear out of both ears, regardless of what he tells our parents when I’m not around. Have we spoken to each other without a mediator present since the incident? You’re damn right we haven’t.

Then, I get called out by Michael Young, who thinks he has everybody fooled with his “good guy” persona on social media. Well, try this on for size: I once coached a teenage Michael Young and he was an absolute terror. One time, I told him he was playing first base instead of second, and he drove a tractor into the bleachers where people had already started to sit down. At least, we thought he did. It turned out he just wedged part of a batting tee between the floor and the gas pedal and used that as a distraction to start firing the pitch machine at the other team’s bus. And then it turned out that we didn’t have a game that day and it wasn’t Michael Young, it was me and I was alone. True story.

I know what you’re thinking: “That’s a lot of thoughts from a guy with a mystery-flavored airhead stuck in his pants zipper,” but you know what, the work never ends. Baseball used to be about vicious competition and stepping on people’s necks, both metaphorically and before the other team’s trainer can run out and help an injured player. When Roger Clemens picked up that piece of jagged wood and tried half-heartedly to murder Mike Piazza in front of 50,000 people? That was the baseball I know. There’s a reason I led the anti-advocacy campaign against baseball’s expanding of safety netting. In the end I failed, but look what MLB got for all of its meddling: A much safer environment for fans. They look like idiots!

In conclusion, think twice before sharing that video. This was a sport invented to cull the herd of human population, both through its violence and imprisoning boredom. Let’s reconsider what our priorities are moving forward, and ask ourselves, is this really the baseball legacy we want to leave behind for our kids? Thank you. Now, please circulate this sign-up sheet to play for my team. The school isn’t interested in my “questionable coaching tactics” so this year our team is going to be “unaffiliated.” No, I haven’t cleared it with the school board. Is the school’s “affiliated” JV coach sleeping in the dugout to prove his loyalty? I can tell you for certain: He is not.

Last week I found myself with a few quiet moments at work. For reasons that I don’t really care to explore deeply I found myself viewing the clip of Brooks Conrad committing three errors in game 3 of the 2010 NLDS. I remember watching the game in real time, the close up shots of Conrad after each of his blunders.

The failure captivates me, because of its totality, and the poetic feel of its inevitability. By the time Buster Posey’s line drive short hops between Brooks’ legs we, as casual observers, can almost roll our eyes at how on the nose this story’s ending feels. This is a morality tale with the morale sucked out, and just one man’s suffering left. It is excruciating. It is like watching Steve Bartman happen three times in the same game. Conrad said afterwards, he wanted to “dig a hole and go to sleep in there.”

A 30-year old rookie, Conrad played nearly a thousand games in the minors over seven years before his big league debut. After Chipper Jones was lost to injury in August, Conrad’s unlikely success helped the Braves reach the playoffs for the first time in five years. Then, in nine innings in front of god, Turner Field, and whatever share TBS pulled that night, it all went away. A promising, feel good story turned into snuff film, filed in baseball’s Eldritch Horror-collection along with Buckner and Merckle.

In a good story, the kind we like to tell and hear, Conrad found redemption later in his career. But he did not. He bounced around the drain of the sport from then until now, when he took over as manager for the Royals’ rookie-league team. The story of his playing career is written, and it will be defined by his glaring, colossal screw ups.

Like I said earlier, there’s no moral there. It’s just the way things played out for Brooks Conrad. He’s still out there, writing lineups, setting pitching rotations, and managing the egos of teenage baseball players in small town North Carolina. He makes it through every day. I suppose, I will too.

My favorite baseball team is currently, despite all odds, in sole possession of first place in the AL West, ahead of the reigning MLB champs. Their era-defining, franchise hero and All-Star second baseman has been suspended for 80 games, and will not be able to join the team in the playoffs, if somehow they make it in. They are, more likely than not, going to do just that.

I’ve spent the better part of the last decade-and-a-half thinking about what I’d feel like when they finally Did It, and to be honest now that it’s here, I’m not entirely sure. It’s strange, really–juggling the excitement that they continue to do the seemingly impossible while denying the inevitable… and that denial just might continue long past the expiration date. Perhaps a nod to Chungking Express’ He Qiwu’s pineapple tins. Or perhaps, a nod to that imaginary calendar which has reset itself to zero each May for the majority of my adult life. I’m not sure which one, to be honest.

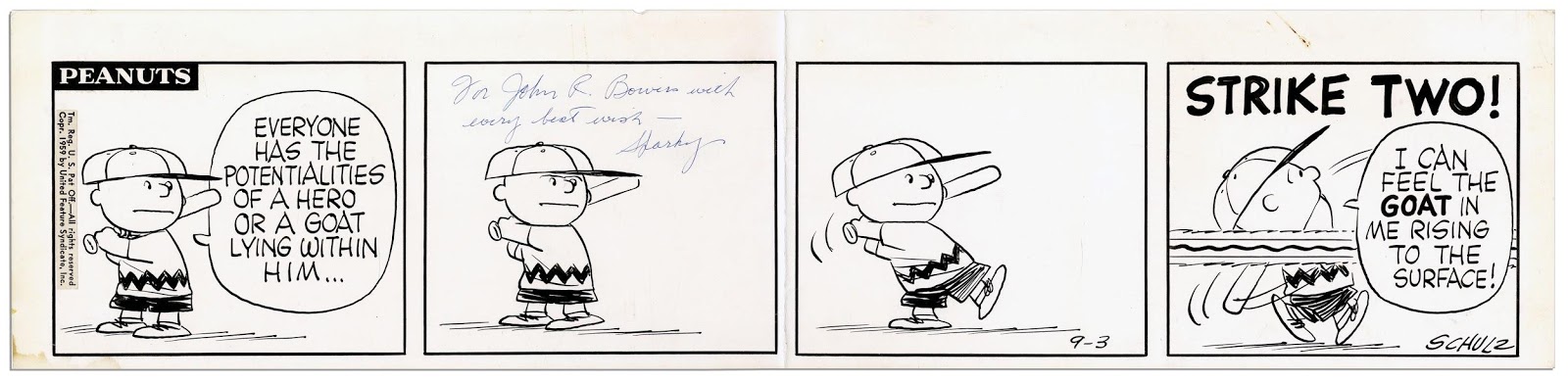

No, instead it has be going back to Charlie Brown–that figure from the 20th Century’s perhaps greatest pop modernist art form, the place where I first learned how to read and the place where I find more resonance as an early-thirties figure of post-modernity trying to make sense of what it’s like to be in this world and to feel, simultaneously, like you aren’t Being in your own skin in the process.

Our hero learns a lesson each and every day–that he is worthless, that he can’t do it, that he should just give up because there are more talented, interesting, and smarter people out there ready to sweep him back into the closet with each and every turn of the page.

I look, knowing that, at the AL standings, and I see a baseball team that stands in first place despite it all, proving the doubters wrong and illustrating that sometimes, just maybe sometimes, the good guys win. That this was meant to be, that finally, our good faith has been rewarded, that we just had the gall to believe for once, that we would receive riches from heaven on earth for our quantified and measured prayer. But Charles Schulz was no advocate for the prosperity gospel. He was, post-Lutheran in his blood, perhaps the American heir to the despair of Ingmar Bergman, albeit a vessel operating at precisely the same time.

I’ve read enough Peanuts to know that this is not the lesson to be learned by Charlie Brown, who has occupied a pitchers mound for longer than anyone, even Nolan Ryan. No, the lesson is that there will always be a strike three waiting on the next panel undrawn, that the moment you feel like you are finally getting what you deserved–imagine that word–is precisely the moment when it all gets taken away from you like a rug pulled out from under your feet.

But still, he goes back, glove on hand, to pitch the fourth. Somehow, I think, that last bit is what so many have forgotten.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now