Baseball is over now, and I am in denial. It always takes a few days for it to really settle in that this isn’t just an off-day, it’s not the All-Star Break, I can’t turn on a game in a few days and have baseball keep me company again. There’s always a feeling of loneliness that settles over me around this time, and that’s why I lean hard into Halloween, the greatest of all holidays.

Halloween involves all my favorite things: candy consumption, societally-sanctioned use of copious amounts of glitter, and absolutely no obligations. No one is getting mad about you skipping out on Halloween dinner or upset that your Halloween gift exchange present is the same pair of slippers Aunt Judith gave out last year. There are no tedious worship services, no disgusting family rutabaga recipes to make because it’s “tradition,” no awkward office party to attend. You don’t even have to hand out candy if you don’t want to! It is entirely an opt-in holiday, and I opt-in 100%.

Halloween also means it’s time for viewing the classics, including the greatest Halloween film of them all: Hocus Pocus. Initially a flop at the box office, Hocus Pocus has now been recognized as the cult phenomenon it is, and this year, its 25th anniversary, has come attendant with a series of re-issues and celebrations. “But Kate,” I hear you saying, “what if there was a poorly-photoshopped all-baseball cast of Hocus Pocus?” Way ahead of you, my hypothetical friend!

Winifred Sanderson

Winnie is the head witch in charge of the Sanderson sisters and a teeny bit obsessed with immortality. Winifred would definitely be a swing-change adopter if she thought it’d extend her career. She also has a fabulous head of carrot-orange hair. She’s basically Justin Turner in drag.

Sarah Sanderson

Sarah is most known for her long blonde curls and her love of running “amok, amok amok!” She’s also the guinea pig of the sisters, the one they shove out into the “icy black river” only to find out that it’s a paved road. Sarah’s main job is luring the children the witches use in their immortality spell. No word on whether or not those children gave her hand, foot and mouth disease.

Mary Sanderson

Although we’re never given the ages of the Sanderson sisters, Mary is definitely the middle sister. She’s always trying to please Winnie, and her special skill is sniffing out children. She’s also got some wild hair that makes it look like she’s permanently wearing a witch’s hat. If Mary was a baseball player, she’d definitely smell her bat.

Max Dennison

Max is ostensibly the protagonist of Hocus Pocus, although his adorable little sister (played by Thora Birch) steals every scene she’s in. Max honestly suffers a little from Boring Narrator Disease, as his most remarkable personality trait is being a virgin. He does save everyone with pretty much no help from anyone else. He’s also an LA native unhappily transplanted to the Northeast, but imagine that in reverse.

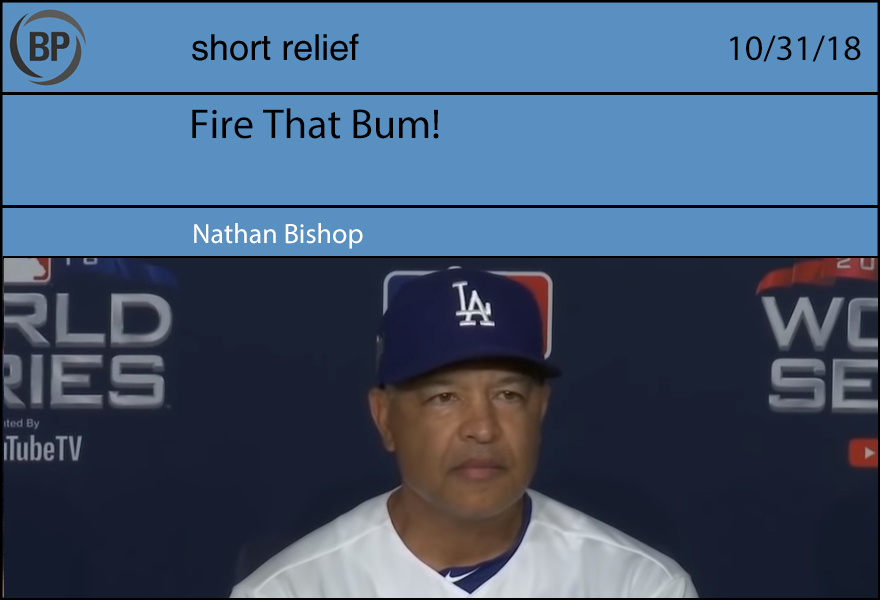

Last week my friend and esteemed editor of this space Patrick Dubuque opined on the emptiness of pretending that baseball’s postseason means anything substantial. Patrick is, of course, correct. He is correct to observe that the baseball postseason is devoid of any lasting, provable, fact. The Red Sox’s victory over Los Angeles does not impart validation of their 108 wins in the regular season, just as the Dodgers’ defeat last year did not cancel out the achievement of their 104 wins. A 100-yard dash after a marathon does not determine who is the best marathoner, and it’s foolish to pretend that the postseason in sports exists as anything more than a way for the league and its owners to extract ever more revenue from its fans.

Beyond the base vapidity of unchecked capitalistic greed, I don’t find much about this disagreeable. After all, it’s not just a sport’s playoffs that are meaningless. All sports—pre, regular, and postseason—exist to distract us from a world in which the things that do matter are increasingly distressing. No, playoffs are good. We all need things to make us smile, and things that make us frown that are easily forgotten. Where the playoff fixation in sport distresses me is when we take its aforementioned meaningless and project it forwards. For this reason I take comfort in the Dodgers.

The Dodgers are a great team, and their achievement in reaching back-to-back World Series is almost certainly, at least empirically, a more impressive feat than winning either either of them. But of course they did not win either of them, and find themselves halfway to Full Buffalo Bills, something one should never, ever aspire to.

The level of frustration to be so close to what we’ve decided is the point of all this, only to fall just short two years in a row must be immense. Still, the Dodgers show no signs of wanting to substantially change the construction of what is from the view of this non-partisan baseball enjoyer one of the two or three best rosters, in the hands of one of its two or three best front offices. They give every indication of wanting to retain Dave Roberts, a fine manager who had a few tough decisions in the World Series go wrong in the worst way.

Baseball forces its participants to not only play a luck-filled tournament after six months of grueling, daily competition, but asks that we all put a lot more weight into the former than the latter. It would be easy to let that weight carry over to the offseason, when Big Choices are made. The Dodgers don’t seem, at this point, to have let it affect them though. They are good, they have been good, and the should be good next year. For something as random as the baseball postseason, that’s probably about all you can hope for.

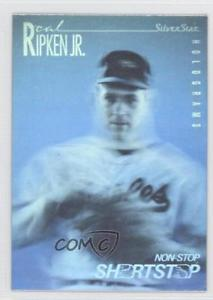

This first item is a hologram card of Cal Ripken in which he exists in three shimmering dimensions, with pair of unblinking serpentine eyes, just as we all remember him. I’m sure we can all recall with ease that night they draped the number “2,131” from the warehouse on Eutaw Street and Cal took his easy lap around the diamond, reluctantly bathing in the adoration of his fans while also blinking in and out of existence on this earthly plane. “Where’d he go?” Chris Berman asked no less than 17 times as Ripken disappeared and reappeared from view. This card has commemorated the moment that Ripken stood perfectly still, right forearm raised ever so slightly, as if to say, “My arm was moving, do you want to take another one?” to a photographer who is muttering, “nah,” while packing up his equipment.

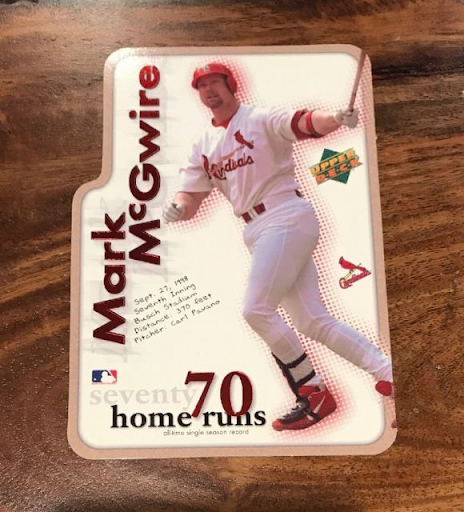

Next up we have a Mark McGwire card that is not quite a rectangle–about an inch and a half down from the top, it juts out in defiance of everything we know about baseball card shapes. This is likely some sort of commentary on the legitimacy of the 70 single season home runs commemorated on the piece: “Yeah, this is a baseball card… but it’s unnaturally bigger and misshapen, isn’t it? Maybe the media should be reporting on this.” The goateed slugger has just completed a swat, watching a ball in its natural state that 1998 season: Moving very quickly away from him. The flipside reveals the details of the event: That McGwire hit his 62nd home run of the season on September 8, 1998, breaking Roger Maris’ record in the fourth inning with a 341-foot blast in Busch Stadium. It even immortalizes Steve Trachsel, the pitcher humiliated by the event. Good luck finding your own copy of this gem–this is No. 814 of a mere 17,000 said to exist.

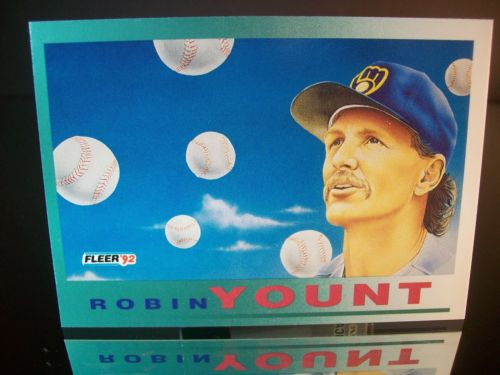

And ah yes, who could forget that magical season when Robin Yount was carried off the field by a cloud of levitating baseballs and transcended to the stratosphere, where he laid eyes upon an unknowable god. His lips parted as though to speak, but no words could properly address the deity that stood before him. The experience, historians agree, left Yount distant and “weird,” able to communicate solely through chanting. We have no actual idea of what occurred for the 13 minutes Yount disappeared from humanity, so this is an artist’s conjecture of the events Yount described shortly before abandoning baseball to live in the Doyne Park Golf Course in Milwaukee and begin a “community of like-minded followers” that everyone knows are just squirrels.

Here are five 1994 Donruss Lenny Dykstra’s in a single case. He is pictured on base, hands on knees, uniform filthy, head cocked quizzically as though his attention his being drawn away from the game. Experts have theorized that this is the moment that his life split away from baseball, as he noticed in the first row of Veterans Stadium a section of stockbrokers advising everyone in their row to buy up shares in a real estate company that exclusively sold condos people already lived in while loudly ordering drugs on mobile phones the size of cinder blocks. “I could do that,” Dykstra is thought to have concluded, and a post-baseball career was born. Again, there are five of these.

Lastly, we have a likeness of Braves star David Justice, brandishing what appears to be a baseball bat that has been altered into a huge tomahawk. Also, he is, as all ball players were in the early nineties, floating somewhere among the clouds and smiling, as if to say, “This is bad, isn’t it? This whole with the Braves, and who they are, and what they do, and this thing I’m holding… it’s all bad.”

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now