November is a light month in the baseball calendar, but not so much for Baseball Prospectus: beyond the hard work of our daily analysts and statisticians, as well as the Transaction Analysis and Minor League teams, we’ve also got people hard at work on next year’s BP Annual and other improvements to the site, small and large. Still, this has been a month of good tidings and joy at Baseball Prospectus, so we wanted to take a moment between Jerry Dipoto’s trades to give thanks, both to our readers and to the game that supplies our work and our happiness. Please enjoy these short paeans from various members of our staff, celebrating some element of our grand old game. And thanks again for reading.

Dried beans aren’t dead. That fact always surprised, and I think slightly horrified, my students. We think of the food we buy as dead, or at least mostly dead. But beans aren’t, at least until they’re boiled. In class, we soaked and sprouted them; crushed them, cooked them, and sprinkled them with acid to see what affected their respiration rates; planted them in egg cartons and Dixie cups; dissected them to reveal their delicate seed leaves, the primary stem curling audaciously up toward the light. Walk down the legume aisle of the supermarket and imagine them, sitting, breathing, slowly enough to not consume themselves in the waiting.

The off-season isn’t quite a bag of beans, but isn’t not not one. Beans and baseball don’t germinate without the right conditions, good weather, good dirt, a spring that feels far off in the midst of the November yucks. I don’t hate it entirely: I read more, see people more, write more, rest more. But I don’t love it either. My house feels too quiet without the TV on, the familiar cadance of the play-by-play, of my dialogue with Bob and FP as they let me know when the no-hitter is, in fact, gone. I’m thankful for the baseball season and thankful for the quiet, especially when I know baseball’s still there, even if it’s breathing more a little more slowly. (Sydney Bergman)

I’m not sure exactly which game it is, but it’s an obscure weeknight West Coast game in July or August in which I have little, if any, rooting interest. Let’s call it Dodgers at Padres on Wednesday, July 11. I’m thankful for this meaningless, late-night West Coast game because it stands for something more: the quiet hour when baseball becomes pure form and ritual, with all content and care about scores and outcomes and standings utterly evacuated. My son is finally down, later than he should be, stretching his 8 o’clock bedtime with Legos, books, and the slow release of energy absorbed by a hot summer day. My wife is upstairs reading, soon to be asleep, probably with the bedside lamp still on. I am in the basement, nominally my office, functionally my baseball-watching room, in something like a meditative state, half watching and half doing other things. Kenley Jansen has walked Wil Myers in the ninth with a two-run lead. Petco comes alive, a little bit. But nothing interesting happens: two groundouts, then a Freddy Galvis fly ball that comes to rest, along with the day’s baseball, in Cody Bellinger’s glove. I turn off the TV, and head upstairs. (John Hegglund)

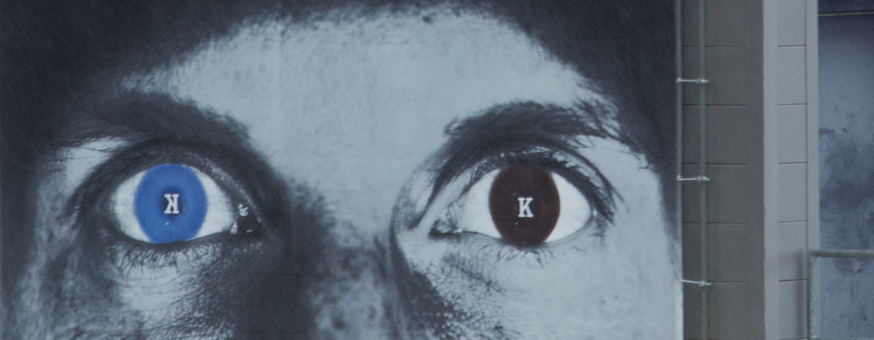

Last year, the Nationals installed an image of Max Scherzer above the right-center seats at Nationals Park. The outsized photograph features his unmistakable eyes with K’s photoshopped into each pupil. Pop art practically popping off a wall, one can imagine Andy Warhol adding it to his output of Factory-produced silkscreens.

In the digital age, the Internet has replaced the Factory and crowdsourced pop art. Scherzer’s sexy eyes are photographed, shared, photoshopped, and shared again, an outpouring of the joy bestowed by the pitcher who gave us certainty in an uncertain age. In 2018, Max Scherzer was someone we could count on. His snarling, stalking presence augured double-digit K’s in every start. When he reached 300, we celebrated as if we’d done it ourselves, and we shared the image again.

In Warhol’s Factory, Scherzer’s image would fade. The cost of repetition, the K’s in those eyes would slowly degrade into softly smudged ink on a screen. That happens to pitchers eventually, but not to Max in 2018. For K’s unfaded on wall and mound, we are very thankful. (Beth Davies-Stofka)

Baseball has a long history of letting us down. It’s always tried to paper over its faults and failings, always tried to sell us heroes and role models. Watergate couldn’t wake Park Avenue up to the fact that the cover-up is worse than the crime. A generation of gritty superhero movies hasn’t convinced them that America likes to see the warts even on its protagonists, that we can better embrace people if we know they’re not hiding something from us.

I’m thankful, then, for Jon Lester’s ennobling contradictions—for a guy who survived cancer with the same brim-pulled-low defiance he’s used to intimidate opposing batters for over a decade, but who has discovered other, more open ways to thrive. Resistant to advanced numbers almost to the point of obstinacy, he’s surprisingly open to new perspectives in more important walks of life. The consummate redass when it comes to a starting pitcher’s job, he nonetheless humbled himself during a nadir of his career, beginning a relationship with the Red Sox’s mental skills guru that set him (perhaps) on a path toward Cooperstown. Unable for several years to throw the ball to first base, he never let that problem infect his more important tosses, and he didn’t hide from the problem or force things or just ignore it and let teams run wild on him. He’s old-fashioned, but unafraid to evolve. We need more like him, inside baseball and beyond it. (Matt Trueblood)

When you grew up in one place but it’s been a minute and now you live in a different place, things can happen to your rooting interests. Fandom can take on complexities.

There are critical exceptions. I lived in New York City for a decade, but that don’t mean the Yankees don’t fundamentally suck.

I moved to Los Angeles nearly that long ago now, but there was no conflict of interest here. Stone-cold opposite corners of North America. The most distant division. Different league entirely. McCourt’s assholery made the Dodgers loveable and cheap. Vin Scully made them magical.

Then a phalanx of well-paid smart people revolutionized the organization. Turned it into the juggernaut that stood there, yet again, before the world. The six-time defending champions of the West. The still-defending champions of the National League. I loved this Dodger team.

We sat in the upper tank, center cut behind the dish, third row. Everyone around us crested in red. We’d all been a part of the same rush on the freefalling marketplace after Game Four. Now we were all a part of Steve Pearce doing to Clayton Kershaw what Johnny Damon did to Jason Marquis. David Price threw it like Lackey. The woman four rows back hollered some shit about the Yankees, then the Astros. Then everybody.

I am thankful that my fandom is foundational. (Wilson Karaman)

Con tanto malestar en el mundo moderno, los clase-medieros (como yo, y seguramente tu también) a veces tenemos dificultad en detectar cosas y situaciones por las cuales debemos estar agradecidos. A eso, súmale que eso del “agradecimiento” es un asunto muy gringo. Pero los que vivimos en los Estados Unidos, en un intento por asimilarnos a nuestras nuevas familias y estilos de vida, hacemos un esfuerzo por echar una mirada a nuestra vida cotidiana y agradecer las cosas y personas que nos rodean.

Podemos estar agradecidos por un internet robusto que soporte varios partidos al día en MLB.tv (agarrándonos de tenues hilos, como puedes ver). Este año, yo no tengo mucho por lo cual estar agradecido. Mi padre murió repentinamente en julio, y esa tremenda pena me hizo dejar de ver el beisbol cuando los Cubs empezaron a fallar a principios de septiembre. No podía soportar dos dolores de ese tamaño en tan poco tiempo.

Pero reflexionando, agradezco que mi papá haya odiado tanto el futbol que me dirigió al beisbol en mi infancia. Gracias a su idiosincrasia, hoy quiero tanto al beisbol, que sacrificar la temporada 2018 fue verdaderamente terapéutico al aceptar su muerte. Gracias por inculcarme el amor por el beis, papá. (José M. Hernández Lagunes)

To be completely honest, it was difficult to come up with something to be thankful for in baseball this year, a year where our eyes have been opened even more to all of the ways that this game we love is inherently and reliably unfair and unequal. What is there, in a sport that treats domestic violence like a discount, and where – despite some small improvements – actually ensuring everyone has a fair shot is an afterthought.

There was one thing, though, that – despite the best intentions of many, and the best effort of a few – was overshadowed by even a dead period in Major League Baseball: The Women’s Baseball World Cup. At a time when most of my emotions towards baseball can best be described as “exhausted,” sitting at home watching women play baseball for hours reinvigorated me in a way little else has. They played in horrible weather, in front of miniscule crowds, on fields that were both a blessing and a curse (a blessing, because the turf meant the daily thunderstorm only stopped play while lightning was in the area; a curse, because baseball played on plastic is painful). They played for a livestream of fans on YouTube, and journalists for the few outlets that listened. For ten days they played baseball. Not softball, but baseball, the same ball and the same dimensions and the same rules and the same swing and the same arm motion and the same love of the game. It was baseball, pure and simple, a reminder of what the sport is at heart – and that you can’t keep half the population away from it forever, no matter how much the establishment may try. (Kate Morrison)

It’s been over a decade since I graduated high school; six and a half years since my wife and I packed up and moved to San Diego. And yet, I can remain close with my friends back home because of fantasy baseball. I might not be able to make the in-person drafts at this point, and we all have day jobs which cut into the amount of time we can obsess over our rosters. But we’ve still got that bond together, so we’re still friends—not just mutual Facebook stalkers.

I played first base in high school, and there’s so much of it that I miss. But the one thing I miss more than I ever thought possible is the little conversations. They’re some of the happiest little conversations I’ve had in my life. Nobody’s in a hurry, nobody’s stressed—hell, the hitter just reached base, he’s relaxed as can be—but the game moves you along, so you don’t get bored with each other. And then, the next guy stepped into my office to chat, life goes on.

I’m thankful for the personal connections that baseball has allowed me to make and maintain over the years. (Colin Anderle)

The average hot dog is a little over five inches long. It’s made to rest comfortably in a small shell of bread which not only cradles the beef or chicken or giraffe meat that’s inside it, but also to allow for the squirting of pre-approved condiments (and those of you in Chicago know exactly what I mean) on top to flavor the sandwich. It fits neatly the average hand and can be consumed in a short amount of time, and is a modular enough portion size that one can eat one or three and still feel part of the experience. It’s an emblematic American food that pairs beautifully with an emblematic American game.

For some strange reason, a baseball game is also the only place in the world where you can find the hot dog’s non-sensical cousin, the footlong hot dog. For one, the footlong sets some unreasonable expectations, checking in a little under 12 inches. It boasts a bun that is near impossible to hold with one hand. The creators of the hot dog made it into something unrecognizable and unwieldy,. It’s even stranger considering that one could instead just order two hot dogs and get the same amount of food. And yet, a baseball game is the best place to sell this monstrosity as well. Whenever I go to a game, I know I’m tempted.

So this Turkey Day, I’m thankful for the fact that a baseball game is a place to see wonderous things both on the field and on the concourse, even if those things don’t make any sense. (Russell Carleton)

En Venezuela no se celebra el Día de Acción de Gracias. Por tanto, cuando tenía unos 8 años y leía o escuchaba que algunos peloteros estadounidenses que jugaban en la Liga Invernal colocaban como condición en sus contratos pasajes para regresar a casa y celebrarlo, no lo entendía.

Pensaba que se trataba de otra excentricidad más como la de Pete Koegel, quien pidió llevar sus perros, o como la de Tim Tolman, de tener un radio de onda corta para poder escuchar los juegos de la NFL, pero cuando maduré, especialmente cuando ya trabajé en el beisbol, entendí que para los estadounidenses era su oportunidad particular de reunirse en familia. Lo mismo que para los venezolanos significa estar en casa durante Navidad.

La situación económica y social hace que ya no abunden los peloteros estadounidenses contratados por los equipos venezolanos, sino que se buscan refuerzos latinoamericanos. Ahora el que celebra fuera de casa soy yo, pero gracias al beisbol cuando aterrice por aquí ya sabía la historia de ese jueves de noviembre y el significado de compartir la mesa alrededor de un rico plato de pavo. (Marco Gamez)

Beginnings, so many beginnings, and then equally as many abrupt endings, leaving only scattered fragments hidden throughout interviews, essays, and newspaper columns. Piecing together an image of the truth and then slowly, methodically tearing it down to reveal what’s underneath, which is sometimes nothing and equally as often everything. This is what I’m thankful for.

Baseball has been built on carefully crafted stories and myths designed to give the game a specific beginning, a specific purpose. In the beginning, and perhaps even now, baseball players were told to be proud of their play and their participation in shaping America’s youth. In turn, baseball fans assumed a pride in supporting these players, in participating in a sport that was far more intellectual, more democratic, more American than any other.

Yet, this year, baseball scratched away at itself, revealing an undersurface of vileness contrary to this pride. Suddenly these myths seemed inadequate in a way novel to many of us, and we now possess more questions, more doubt, more shame in our fandom than was the case in March.

Shattering the image of what we profess to love is uncomfortable, arduous, and emotional. But it’s necessary. And so I find myself thankful for and indebted to those who first worked to safeguard the truth. It is their interviews, essays, and newspapers that contain the truth, and within the truth is everything, including hope. (Mary Craig)

I spend November reminding myself that March exists, and though every November I’ve known has eventually ended and March has eventually arrived, I am difficult to convince of this truth. Why March? March is the best month for baseball—the month in which anything, everything, is still possible, and the month in which there are games. In more recent years, there are even baseball games that matter in March. March 2019, which is still to come, will bring with it an opening series in Japan, a whole heady week before traditional opening day, and March 2018 set up the best Phillies season since 2012. At 80-82, the 2018 Phillies didn’t quite meet their PECOTA projection (or my own fanciful hopes), but for the first half of the season, they were better, far better.

So I’m thankful for that, for the wild spring of optimism that led me to hypothesize that the 2018 Phillies might sniff 90 wins, even though they didn’t. I’m thankful that, for the first time in a long time, there was even an outside chance. (Holly M. Wendt)

When I was growing up, I was taught to idolize Kirby Puckett, and so I did. He was a delight as a ballplayer, as exciting with the bat as he was in the field, and he was universally praised as a leader and as a great person. Kids like me loved him. I have his autobiography, in which he talks blandly about lifting himself up out of poverty and making himself into a Hall of Fame-caliber ballplayer. Nowhere in it does his mention abusing his wife or his philandering.

I found out about that in 2003, by which time I absolutely should have already known better, when Puckett allegedly sexually assaulted a woman in a restaurant bathroom and his entire carefully cultivated image came crashing down around his shoulders. Later that year, a Sports Illustrated article by George Dohrmann catalogued my hero’s many sins.

This Thanksgiving, as he rides off into retirement, I’m thankful for Joe Mauer. Puckett was everything Mauer wasn’t: flashy, dynamic, boisterous and false. And while I can’t know Mauer’s heart, I’m confident that my kids, who have grown up watching and idolizing him, won’t have to learn the same lesson I did. At least not about this. They had a hero worth admiring. And they can wait a few years before disillusionment creeps into their lives. They get to be kids, and I get to enjoy them as kids, just a little longer. (Mike Bates)

I’m thankful for the inspiration baseball provides. Not the smells or the sounds or the sun setting over the stadium; I mean the characters it uses to tell a neverending story about nothing.

I love that these baseball guys, so many of them, are sinister cartoon billionaires conniving for your money, shameless cheaters trying to convey information through a system of strategic claps, scatterbrained outfielders hurling sticks in celebration, bombastic superagents thumbing through a thesaurus the night before a press conference to compose a string of ludicrous soundbites, and sniveling writers who parade as tough guys or guardians of an ancient religion, who can only report on this sport through clenched teeth or glassy eyes.

With a deep historical catalog full of asinine subplots, schemes of corruption, and unthinkable odds, baseball continues to be a generator of stories to be pointed and laughed at, and I will be forever thankful that it never lets me run out of ideas. And also, you know, the eternal bond its strengthened between myself and my family now and in the future, etc., etc. (Justin Klugh)

I’m thankful baseball’s boring. It’s trying not to be, and that’s a dang shame, but all other sports try to jam-pack their action into the smallest amount of time, separated only by beer commercials and/or injury timeouts, which are typically used for beer commercials. This most accurately applies to basketball, hockey and Greco-Roman darts.

Not to get all George Will on you but its elegance lays in the action less times. It gives you time to think. Ball outside. Not a bad day outside, at least this beats work. Ball two. Uh-oh, the pitcher needs to throw a strike here. Your emotions gradually oscillate between the game and the world around you. The rhythm of pitches makes it so. The pitch is the irreducible unit and the time between allows each pitch to breathe. A ball in play becomes an entire vignette. It’s sports jazz.

Also those long pauses in between moments of action are perfect opportunities to post the jokes. See, even the baseball inventors 200 years ago were thinking of this sport with content in mind. (Matt Sussman)

Lo que le agradezco al béisbol

En perú, un título de filosofía no abre muchas puertas. Normalmente, al graduarse, uno se dedica a la academia. Pero, había decidido que eso no era a lo que quería dedicarme. Entonces, ¿qué hacer?

Durante mis estudios, trate de dedicarme a escribir sobre béisbol. Un par de artículos, análisis, e intentos de blog surgieron cada cierto tiempo. El béisbol de fantasía era un escape recurrente, algo a que aplicar estos análisis simples para tratar de sacar alguna ventaja.

Un dia, mi padre se topó con un reporte que había armado en Excel. Me estaba preparando para el draft del 2012, creando modelos para armar mis proyecciones. Mi padre entendió lo que estaba haciendo y me introdujo a libros de econometría, cálculo, y estadística. Quedé cautivado. ¿Quién pensaría que estas habilidades me podrian servir en el mundo real? Fue ahí, gracias al béisbol y mi padre, que mi vida cambió de rumbo y comencé a dedicarme a los números – sin abandonar las letras.

El béisbol me dio un giro a mi carrera. Me llevo a querer aprender más, dedicándome a su estudio e investigación. Me ha llevado a nuevos retos, nuevas preguntas, y nuevas amistades.

Por eso, le estaré eternamente agradecido. (Martin Alonso)

The realization I have suffered from anxiety most of my adult life came all too recently. Seemingly simple tasks take far longer than they should, if they get done at all. Panic attacks and yours truly are longtime companions.

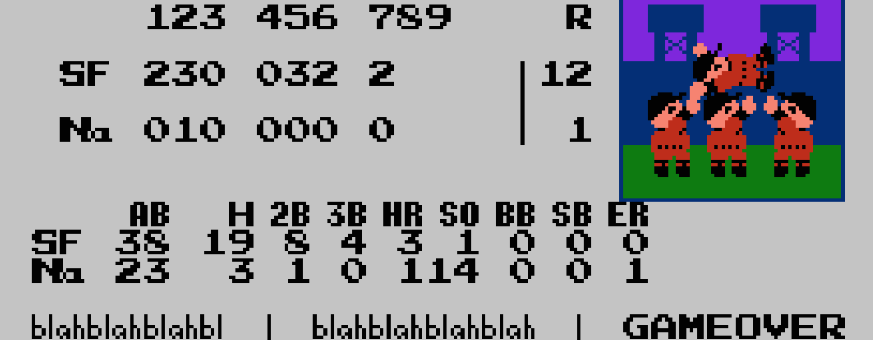

There’s a website where you could play the original RBI Baseball; by summer it was a daily late night ritual. I demolished two keys fairly quickly before finding the right touch. It is usually a calming experience, where all which exists is myself and a noble quest to defeat nine opponents in a row in games not lasting more than 15 minutes. I succeeded doing this playing as all 10 of the available teams, so I started all over again, now with the same time limit but not dipping into the bullpen at all. The difficulty level is the perfect balance between not easy and not impossible. I much appreciate how RBI’s universe is wonderfully small compared to something like Fallout. Things are a little better than they were last Thanksgiving thanks to this ancient video game, as well as some other garden variety, boring self-care exercises. I am beholden to them all. (Roger Cormier)

Manny Machado’s lack of hustle and supposed poor attitude are what I and every other Yankees fan should be thankful for. If not for it, the team would almost assuredly sign him to a massive deal that would require the Steinbrenners to cut a luxury tax check next year. That would be terrible.

Finally, after all the naysayers said they couldn’t do it, the Yankees avoided the dreaded tax this season. Hopefully, that trend continues. There’s no need for Machado, or any other pricey free agent, when it means the most valuable franchise would have to pay some silly tax. I’m so thankful that the Steinbrenners made a little more money this year.

Hal, I hope this message finds you well. I know you were struggling financially, and rest assured that the rest of the fanbase has been far more concerned about your finances than the success of the team. I think I speak on behalf of the entire fanbase that we are all so thankful that you saved all those millions of dollars. We’re appreciative of your efforts and are pulling for you! (Derek Albin)

I like following a sport where it is perfectly acceptable, if anachronistic, to write down everything that happens during the game as it’s being played. I am thankful for C.S. Peterson’s Scoremaster Official Baseball & Softball Scorebook. You don’t walk into other sports arenas carrying a pad of specially-designed pages, the first of which instructs, “How to Operate This Scoremaster.” Operate!

The pace of baseball gives you time to follow the action, peruse the scoreboard, and carry on a conversation, all while marking down the outcome of every pitch. You can keep score while you’re eating peanuts or drinking beer. (And it’s a great excuse to get your friends to stand in the concession lines for you. I’m keeping score!) And if someone asks, “How many strikeouts does he have?” or “When’s the last time they hit a ball out of the infield?” you’re the sage of the section.

Then, when you fill the book, you can put it on your bookshelf. You might not ever look at it again, but it’ll sit there, a 25-page testament to an equal number of games at the ballpark. Or, if any games go beyond each sheet’s limit of 12 innings, fewer. (Rob Mains)

In the most frustrating year of baseball watching in my adult life, there was little in which to find joy. My Cubs won 95 games, but they did so in a frustrating, sometimes irksome manner, all while employing players whose off-field actions and words made it difficult to root for the team.

And so this year I’m thankful for Javy Báez. I’ve been a Javy fan since he rocketed up the Cubs top prospect lists, in my nascency as a “knowledgeable” baseball fan (and writer). For years, he was touted as a “unicorn,” with defense and speed and light-tower power, but until this year, only the former two qualities really made an appearance in the majors. Sure, his legend grew with his 2016 NLCS MVP and his steals of home and his tags, but this season he finally proved us right: his transcendent hitting manifested in Chicago, and his palpable excitement and joy for playing livened a dead-ass Cubs team. He was rewarded with a second-place finish in MVP voting, cementing the legend of El Mago and giving the cadre of Cubs fans who never doubted him the satisfaction of watching a long-loved player’s skills come to fruition.

Other Cubs are great players with likeable personalities. But Javy is ours, and the joy I feel isn’t just personal—it’s collective, pulling people together in a time when we, as baseball fans, could use a little more of that. (Zack Moser)

I get it, attention spans are short these days, but I’m thankful for what separates baseball from any other major sport. There’s something special about looking at the scoreboard and not seeing a clock counting down to the inevitable end of the game. Baseball games do end. Some games take longer than others to end, but why are we so concerned about all of this? Can’t we just sit back and watch the game?

Ever since he took over as commissioner in January of 2015, Rob Manfred has been focused on speeding things up. His pace of play initiatives so far have included shortening the time between half-innings, requiring hitters to keep at least one foot in the batter’s box throughout an at-bat and most recently, limiting mound visits. All of this is fine with me. Who would argue that a catcher trotting out to the mound to chat with the pitcher multiple times during the same at-bat isn’t annoying? But now there’s talk about adding a pitch clock. So far, it’s just talk with few details, and I’m thankful for that. Thank you, baseball, for giving us the opportunity to lose track of time, at least until the game is over. (Zach Steinhorn)

Baseball in general, and Baseball Prospectus specifically has given me a community that I’m thankful for. It started with a book that wife gave me, Baseball Beyond the Numbers. After reading I reached out to the book’s editor, Jonah Keri, who graciously declined my fantasy baseball league invitation. From there I became a subscriber, started reading more and found that there were a ton of really smart, interesting people who thought critically about baseball. This was news to me: I grew up around Chicago and am a fan of the Cubs. While taking in a game at Wrigley Field, you’re more likely to get barf on your shoe than you are to have an in-depth conversation with someone sitting near you. The closer look at the game was intoxicating.

Then came Up and In. Their 102 episodes are just as easy to listen to and learn from today as they were in 2012. I live in the Pacific Northwest and when I saw that there was going to be a ballpark event in Seattle, I jumped at the chance. When I had a second chance a couple of years later, of course I would take that in as well. Harry Pavlidis was at that event. We met and chatted briefly, and I followed up with him after about working on the BP website. This opened the floodgates. With this, I was exposed to the community of kind, generous, super smart and talented people that are in and around Baseball Prospectus. I now host a podcast with Harry and I count myself extremely lucky, proud, and grateful to be a part of the team. (Kendall Guillemette)

I’m thankful for my personalized Butch Hobson autographed photograph. My father got this for me at some fundraiser in western Massachusetts during the time when Butch Hobson was managing the Red Sox (He was the manager from 1992 through the strike-shortened 1994 season).

I just got off the phone with my father, who didn’t remember many of the details of the particular event, but he did remember that the main item that they was being auctioning off a Mickey Mantle jersey. While he didn’t remember the event, he did remember — off the top of his head! — that Hobson hit over 100 RBI and had a 30 home run season batting from the 9th spot in the lineup. Sure enough, in 1977 Hobson had 112 RBI and 30 home runs (though, full disclosure, he hit primarily in the 7th and 8th spots). While still on the phone I told my dad that in that same year Hobson also led the league in strikeouts with 162 and by dad responded with, “That’s the Butcher!” (Note: My dad loathes high strikeout guys).

I now present to you my personalized Butch Hobson autographed picture. It’s says simply, “To Greg. Butch Hobson.” (Gregory Matthews)

I never cared for replay. I doubt most people do; most of us accept it, or perhaps we love the promise that replay delivers, the idea of getting it right. But getting it right, defining just what right was, quickly grew more complicated than our aesthetic sensibilities preferred: the idea of the transfer rule, and the foot on the bag, and the microscopic space between our cells. It was the moment that anatomists first searched the body and found no cavity for the soul, or when Heisenberg ripped physics out of our hands.

I never cared for the sciences. I was a philosopher, a relativist, a hero: I was happy to let the bad calls go against me if the dice rolled that way. I was fine with the Dekingers of the universe. But now… getting it right may never quite be possible, but in an era where truth has suffered on the cultural exchange rate, I’m glad for the striving. I’m thankful that we have a game where the results are the results, and can’t just be revised the next day, that this one language between people still holds, barely, upon further review. (Patrick Dubuque)

As a skinny, awkward, homeschooled nine-year old, baseball gave me friends. It gave me something to be good at, that other people my age could appreciate. It gave me travel, along the main and back roads of the Pacific Northwest. My first nights away from my family were spent in places like Chickasha, OK, and Kingsburg, TN; a still awkward teenager running and sweating around the basepaths of dusty diamonds, thousands of miles from home.

Growing older, baseball has given me a canvass through which I am slowly learning to express myself, after decades of repressed emotions and thoughts. It has given me a place to feel safe, and comfortable, and at ease, when most everywhere else chafed and scuffs my soul like coarse sandpaper.

Baseball gave me a no-hitter with my son. He does not love sports like I do, but for one day, when the final out nestled into Austin Jackson’s glove, he held me and wept with joy as though the very purpose of his life had been fulfilled.

Finally, or rather most recently, because baseball seems intent on giving to me in ways old and fresh for the entirety of my life, it gave me last Sunday. There, on a crisp sunday afternoon, I stood in a backyard with my families of marriage, birth, and baseball. We laughed, joked, drank, and watched children played wiffleball. There are a million problems in the game today, but, true or not, I can choose to believe that as long as we can whack a ball and a stick, and run around in circles in the sunshine, we have sufficient armor to do battle against them.

For these things, and more beyond words, I give thanks. (Nathan Bishop)

Thanks to Rob McQuown for research assistance.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now