While we all await the return of baseball, whether on the sandlots or in the stadiums, there are still ways to scratch that horsehide itch: The game in other media, such as films. To assist you in your search for the highest-quality baseball films to enjoy (or perhaps the lowest-quality baseball films to laugh at), Baseball Prospectus is reviewing them all, from the popular to the obscure. After every five reviews, we’ll update our overall rankings.

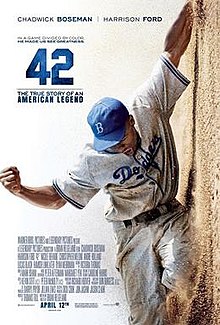

42 (2013)

Genre: Civil rights drama.

Logline: Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey signs Negro Leaguer Jackie Robinson to integrate major league baseball.

Starring: Chadwick Boseman in his first notable starring role; Harrison Ford doing some rare character work. Also: Nicole Beharie, André Holland, Christopher Meloni, T.R. Knight, Alan Tudyk, John C. McGinley, Max Gail.

Writer/Director: Brian Helgeland, who won an Oscar for cowriting L.A. Confidential (1998) and was nominated for another for Mystic River (2003). This was his fourth directorial effort and first in a decade after the failed Heath Ledger film The Order, also in 2003.

How Realistic is the Depiction of Baseball? The players’ actions pass muster, but the film gets various details wrong, including pitchers Fritz Ostermueller and Dutch Leonard throwing with the wrong hand. The costume department (led by Caroline Harris) makes the common mistake of focusing on the uniforms being old rather than accurate—using felt for cap logos that were embroidered, using too dark a shade of blue for non-Dodgers teams, and placing the team names to low on the jerseys.

Real-Life Baseball Cameos: LOOGY-turned-broadcaster C.J. Nitkowski as veteran Phillies right-hander Dutch Leonard.

Typical Baseball-Movie Cliché: The hero gets delayed vengeance on a pitcher who threw at him, homering off him later in the movie.

The details of Jackie Robinson’s integration of major league baseball are as familiar and important to baseball writers and historians as Bible stories are to the devout, so when 42 was released, I avoided it, fearful of Hollywood’s twisting of the scripture and of having Robinson, Rickey, and the rest replaced in my head by the false idols of Boseman, Ford, and company. Still, I was under the impression that the film did a competent job of relating the fundamental story. I was wrong.

Largely a bloodless reenactment of the familiar beats of Robinson’s signing and rookie season, 42 fails to add any life or depth to those familiar anecdotes, fails to convey the stakes of Rickey’s great experiment on an emotional or cultural level, and even fails as entertainment. Despite strong lead performances by Boseman, Ford, and Nicole Beharie (as Rachel Robinson), the film is inert. I spent the bulk of its 128 minutes waiting for it to kick into gear before realizing it never would.

It ends with a fizzle as well. It finishes neither with Brooklyn winning the pennant, nor with Robinson and the Dodgers’ success in subsequent seasons, his MVP award in 1949, the lone Brooklyn championship in 1955, his Hall of Fame induction in 1962, or even his Rookie of the Year recognition for that fateful first season. Nor does it show the impact of Robinson’s pioneer season, which opened the door to a flood of great African American players, changed the league and the country for the better, and arguably kicked off the civil rights movement (no less a figure than Martin Luther King Jr. cited Robinson as inspiration). Rather, it ends with that supposedly vengeful home run off of Ostermueller, a fourth-inning solo shot that opened the scoring in a game the Dodgers won 4-2, clinching a tie for the pennant but not winning it outright.

That home run was actually the second Robinson hit off Ostermueller in 1947 after the Pirates lefty hit him with a pitch in their first confrontation on May 17. Robinson also stole home against Ostermueller in late June, breaking a 2-2 tie with what proved to be the winning run of that game, a scenario with arguably far more drama than Helgeland managed to invest in that late-season solo homer.

The film’s greatest offense, however, is its failure of perspective. This is very much the Robinson story seen through the eyes of a white filmmaker. The only character who registers as a multi-dimensional human being is Rickey, delightfully embodied by Ford, devouring scenery as the gruff, cigar-chomping, eyebrow-wiggling old man bursting with cranky righteousness. The internal life of the African American characters, the precious few that get significant screen time (really just Jack and Rachel Robinson and Hall of Fame sportswriter/advocate Wendell Smith), is nonexistent.

We open on Robinson playing in the Negro Leagues and see him traveling with the team (just so Helgeland can present the “take the hose out of the tank” story), but we never see his teammates’ reaction to the news that the Dodgers want to or have signed him. We never see him or them discuss their excitement or anxiety or jealousy about the opportunity or see them react to his struggles and successes (addressed via Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in the 1996 HBO film Soul of the Game). Similarly, we never see Jackie confide in Rachel. We don’t even get the clichéd scene of the wife receiving death threats at home. Rather, we have Rickey pulling Robinson’s hate mail from a filing cabinet to show Pee Wee Reese, as if the white character’s reaction is all that matters. We see black fans cheering for Robinson in the stands, and an elementary-school-aged Ed Charles determined to follow in Jackie’s footsteps, but we never see the impact on the black community, no one out living their lives following along on the radio or in the newspaper, or discussing Jackie among themselves.

Helgeland’s lone attempt to portray Robinson’s internal emotions rings in the film’s nadir. After checking the box requiring him to depict Phillies manager Ben Chapman’s racist taunts, Helgeland has Robinson retreat to the tunnel behind the Dodgers’ dugout and throw a tantrum. The film’s consultants, Rachel Robinson and Ralph Branca, both asserted that it never happened, but there is Boseman’s Robinson breaking his bat on the cinderblock wall, screaming, crying, and falling to his knees in tears, only for Mr. Rickey to arrive and help Jackie find his strength. The scene is incredibly offensive, both to Robinson’s legacy and on its own merits—it makes Chapman more powerful than he really was and travesties Robinson’s ability to transmute outer abuse into inner fire. Robinson and the other African Americans in this film are limited to three roles: avatar of nobility, victim, or child.

Spike Lee shared the screenplay of his unproduced Jackie Robinson biopic in late March, a script which, unsurprisingly, contains much of what was missing from Helgeland’s film. Indeed, Lee’s script, which he spent years trying to get financed, shows more interest and compassion in Robinson the man, and more effectively captures his cultural significance, in its first three pages than 42 does in all of its 128 minutes.

This Movie’s WAR: 1.0. The acting is good, the filmmaking is competent, and those signature moments are all there (“I want a player with the guts not to fight back,” etc.), but this film is a prime example of what King called the “polite” racism of northern liberals and does a distinct disservice to Robinson’s legacy.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now