It’s hard to imagine the world of April 28, 2012. It can be tough enough to imagine the world of March 28, 2020 these days. Albert Pujols had only just begun his beleaguered career as an Angel, Chipper Jones was in his swan song season, and Ozzie Guillén was managing the flashy, revamped Marlins. (That somehow wasn’t a mere fever dream.)

April 28th in particular was destined to stick in the baseball record books. In Cleveland, the Angels had recalled Mike Trout for his second go-around in the big leagues. Although this news garnered plenty of attention since Trout was still a huge prospect, the biggest buzz that day was in Los Angeles, and with all due respect to ’60s Dodgers icons, it wasn’t because it was Don Drysdale/Maury Wills Bobblehead Night. A teenage wunderkind named Bryce Harper was making his MLB debut.

Countless fans had been thinking about this day ever since Harper graced the cover of Sports Illustrated as a high schooler in June 2009. He’d appeared in 23 different Baseball Prospectus articles before he was even drafted, not a small figure for 2009-10 content. He was supposed to lead baseball’s next generation, and the attention was even more intense than when Nationals teammate Stephen Strasburg made his own highly-touted debut nearly two years prior. Harper had been followed from high school to junior college and all around the minor leagues. Anything he did—whether it was a walk-off blast, an ejection, or blowing a kiss—was brought to light.

The media were ready. It’s hard to even find Harper in this pregame picture:

“We haven’t seen anybody this scrutinized, this polarizing, at the start of a major-league career,” said Tom Verducci. “If anybody wants to compare Bryce Harper to anyone who came before him, it doesn’t work. There are no comps to what he went through to get here.”

Some of this footage would later make its way into a short film about Harper’s rookie season, Bryce Begins. How many teenagers already have documentaries in the works about them? It was mayhem, and that was going on while everything else from Harper’s debut carried their own stories.

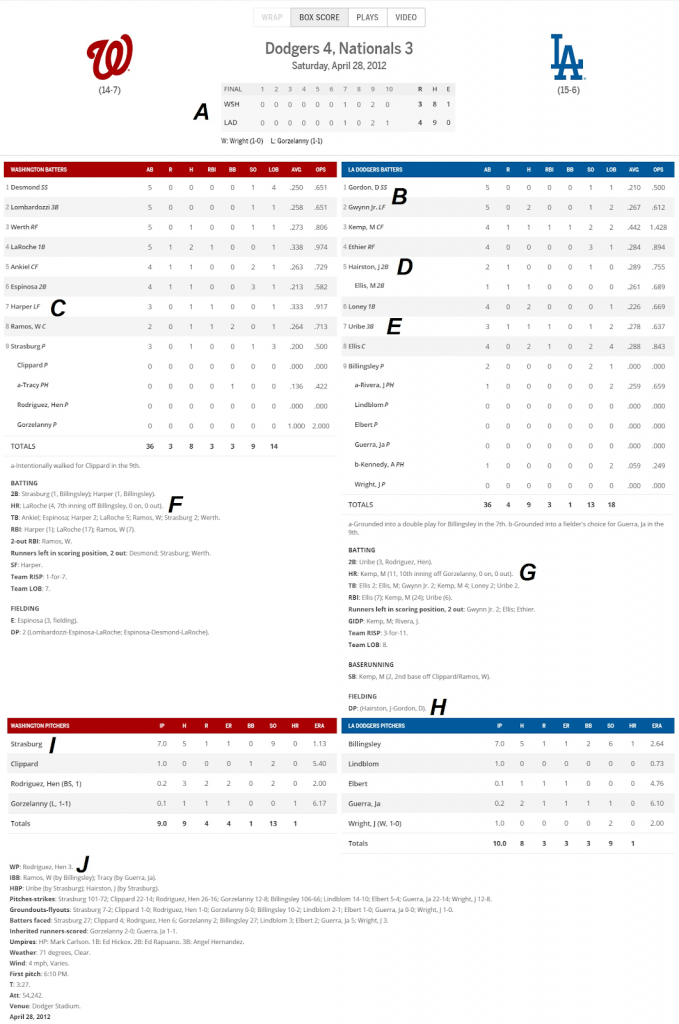

A

The matchup itself carried its own implications. Both the Nationals and the Dodgers would dominate their divisions over the next decade. As Vin Scully noted at the start of the broadcast, “This might be a dandy.”

These Dodgers were in the process of being sold by Frank McCourt, and were still led by Ned Colletti and Don Mattingly. They were a year away from beginning their streak of seven consecutive NL West crowns, albeit with often-rotating cogs. Matt Kemp and Andre Ethier were the heart and soul of this offense. Clayton Kershaw was coming off his first Cy Young season, but he wasn’t starting on this night; that task went to Chad Billingsley.

Meanwhile, the Nats were another team on the rise. They were essentially a .500 team in 2011, and with the Phillies aging out of their run of NL East dominance faster than expected, an opening appeared. The emergence of Harper and Strasburg was at the heart of the surge, but there was also Jayson Werth, Ian Desmond, Gio González, Jordan Zimmermann, and original Nat Ryan Zimmerman (whose injury led to Harper’s call-up). As so often seems to happen, the young talent pushed them to October baseball sooner than expected.

B

The 2019 Blue Jays received a good deal of press for their lineup of four second-generation players in Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Bo Bichette, Cavan Biggio, and Lourdes Gurriel. However, this game alone had three players on each side with close ties to former pros.

The Dodgers had Dee Gordon and Tony Gwynn Jr. hitting back-to-back at the top of the lineup, and Jerry Hairston Jr. in the middle. On the other side, the Nats had Adam LaRoche, Steve Lombardozzi, and Werth, whose step-father, Dennis, played four years of his own. Neither trio is quite the Jays’ quartet, but not too shabby, either.

C

Remember that Verducci quote about no one being as highly scrutinized in his debut as Harper? The dude got booed in his first career at bat, which ended in a groundout. Harper claimed that he liked boos because they helped him focus, but still. Rough.

The jeers didn’t deter Harper for long, as he crushed his first career hit, a double to dead-center against Billingsley:

Look at that helmet (intentionally) fly off. That’s a man ready to tackle the spotlight. Later, Harper would have an even more crucial at bat, as a ninth-inning sacrifice fly led to his first RBI and briefly put the Nats in front, 2-1. He could’ve been the hero in his major-league debut if not for a poor bullpen performance.

One bonus to Harper debuting at Dodger Stadium was that Scully got to be on the call. He relayed the story of Harper choosing No. 34 because the numbers added up to the No. 7 of Mickey Mantle (à la Jason Giambi). Scully remarked that he remembered watching Mantle first reach stardom in the Fall Classics of the early ‘50s. Of course he did; after all, Scully was broadcasting in Brooklyn at the time and 60 years later, he got to see Harper, too. Although the Mantle comparison would soon fit Trout better, he continued to be linked to Harper for quite awhile.

D

Another first that Harper could’ve notched in his debut under better circumstances was an outfield assist. A seventh-inning single by A.J. Ellis went to Harper, who made an excellent throw home that should’ve nabbed Hairston at the plate. The only problem was that Hairston did a sneaky good job of slapping the ball away from Wilson Ramos. Instead of running into an out, the Dodgers tied the game. There might not be extra innings if Ramos holds onto the ball here. Oh well.

E

Bunts were already fading in 2012, as there were 1,479 successful sacrifices, down 188 from the previous season. Jumping ahead to 2019, bunts hit an all-time low of 776. Almost half the bunts that fans used to see as recently as 2012 just don’t happen anymore.

One failed bunt attempt that you wouldn’t see today happened in the seventh. Mattingly asked Juan Uribe to lay one down with no one out and runners on first and second. Even though the bottom of the lineup was due up next, the bunt was considered the better play. Arthritis and other ailments would soon plague Uribe’s 2012 season, but Mattingly was still asking someone with just one successful bunt on his record since 2009 to give Strasburg a free out.

Uribe couldn’t get the job done. He fell behind 0-2 and struck out.* Yes, Hairston ended up scoring anyway to tie the game, but they could’ve had more. In all fairness to Mattingly, the Nats’ Davey Johnson called for a questionable bunt of his own in the ninth with Rick Ankiel (he of eight career sacrifice bunts) batting with a runner on first and no one out. Ah, 2012.

*Uribe would have a much more memorable time at bat after a failed bunt in Game 4 of the 2013 NLDS against the Braves.

F

Another sign of the times: LaRoche was the Nats’ cleanup hitter and Scully dubbed him “the Nationals’ primary RBI producer,” even though he had a .546 OPS in 2011 and Werth overshadowed him as the lineup’s veteran presence.

However, the last laugh’s on me. LaRoche homered for the game’s first run and led the club with 33 homers (and yes, 100 RBI). He went on to finish sixth in NL MVP voting, even though five of his teammates had a higher WARP. Once again: Ah, 2012.

G

It’s easy to forget just how much of a world-beater Kemp was considered in April 2012. His previous season was a 7.9 WARP romp that ranked among the best in Dodgers history, one that probably should have earned him MVP honors. He came a homer shy of going 40/40 and had to settle for runner-up to Ryan Braun, though he still paced the league with 39 dingers.

Kemp kept the excitement in the air around Dodger Stadium entering 2012, as he voiced dreams of a 50/50 season. He entered play hitting .452 and kept up a sensational April by swiping a bag and bashing his 11th homer of the month, a walk-off shot in the 10th that gave the Dodgers the win:

This was the kind of baseball demi-god who the Nationals hoped Harper would become. In a way, that dream came to fruition.

By mid-May, Kemp was still on top of the baseball world, and the Dodgers were six games ahead in the NL West. On May 14th, he hit the then-DL for the first time in five years with a hamstring injury. Kemp returned at the end of the month, promptly pulled the hammy again, and this time was gone until after the All-Star break.

The Giants snatched away first place, fended off the Dodgers for the title despite the massive Adrián González trade in August, and Kemp’s OPS fell from 1.163 in the first half to .792 in the second. He had a torn shoulder labrum that required offseason surgery. From 2013 onward, Kemp would remain a productive hitter when healthy, but the all-around superstar was sadly gone for good. It’s a big ol’ bummer.

Kemp chased the ghost of his 2011 for the rest of the decade, much like how Harper’s otherworldly 2015 has dominated the conversation around him. Roughly 27% of Kemp’s 28.9 career WARP is concentrated in 2011; Harper hopefully has many productive years to go, but for now, his 2015 WARP consists of 31% of his career total.

H

Jerry Hairston Jr. could play some damn defense all around the diamond. That is all.

I

Strasburg’s career began two years before Harper’s, but due to his Tommy John surgery, this was only his 22nd MLB start. Strasburg starts were still big events, though as Scully noted, this was one of the first times that the pregame scrum wasn’t centered around him. It must have been a nice feeling to have the pressure shifted elsewhere for once. The phenom brought some filthy stuff to this outing, striking out nine Dodgers while making them look quite silly.

That knee-buckling curve to fan Ethier in the second is especially gross. As an added bonus, Strasburg slapped a double off Billingsley for his first career extra-base hit. He’d actually go on to win the Silver Slugger that year among pitchers. The man could do it all … until his team infamously shut him down before its doomed NLDS against the Cardinals.

J

It was a bit of a shock to see who the Nationals called upon to close out this potential victory in the ninth. I may have been distracted by my senior year of college at the time, but I still had a pretty good sense of who the vast majority of baseball players were. Scott Elbert? Check. Tom Gorzelanny? No doubt.

Henry Rodríguez? Unless it was the popular ‘90s Expos outfielder, I had no idea who this was.

Since incumbent Drew Storen was injured for the first half, Rodríguez was tabbed as the Nats’ closer early on in 2012. I had always assumed that it was Tyler Clippard‘s job from the get-go, but he was only the setup man. Davey Johnson liked Rodríguez’s hard fastball and thought that he projected well, even though he was prone to walks and led the NL in wild pitches in 2011. So far in April, Johnson felt good about his decision, as Rodríguez had saved five games and allowed just one hit in the process.

It all came apart on this night.

Four hits and three (!) wild pitches helped the Dodgers tie it up when the Nats were a strike away from victory. Before the ninth was over, Rodríguez had been hooked. A nightmarish May followed, and Rodríguez was demoted from the closer’s role in favor of Clippard. He failed to make the eventual playoff roster and has not pitched in the majors since May 2014. Scully gets the final word on the Nats’ reaction to Rodríguez:

“It’s ‘Oh, Henry’ all right, but it’s not the candy bar.”

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now