This article was originally published on Sept. 3.

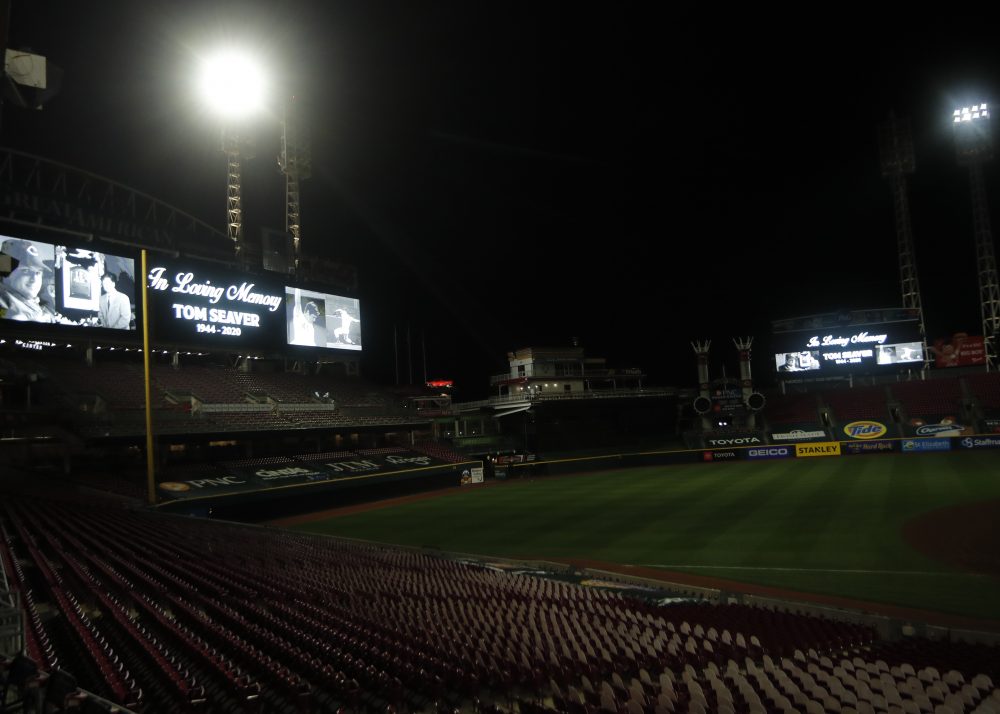

Tom Seaver, Hall of Fame pitcher and winner of 311 games, has died. According to a press release by the Hall of Fame, he passed away due to Lewy body dementia and COVID-19 on August 31. He was 75 years old.

Early last year the Seaver family announced that he had been diagnosed with dementia and would be retiring from public life. It was for that reason that the 50th anniversary celebration of the 1969 Mets’ unlikely World Series triumph over the Baltimore Orioles had to take place without the team’s best player. That was a blow; Seaver had not just been one of the greatest pitchers of all time, but one of the most intelligent and thoughtful, whether when discoursing on pitching or other subjects. He pitched in the major leagues from the age of 22 through the age of 41, and so time eroded his great arm before our eyes. That was to be expected. That time would also erode his mind was harder to accept.

It is also painful that the scourge of this miserable year, COVID-19, played a part in his passing. But it is appropriate, because Seaver was sensitive to current events. In 1969, with the Mets on the verge of that first World Series after five 100-loss seasons in eight years of existence, Seaver took note of that miracle-in-the-making and said, “If the New York Mets can win the World Series, then we can get out of Vietnam.” That was on October 10, the day before the Series began. The Mets did win the World Series. The United States did not get out of Vietnam. Two months later, on December 31, 1969, a small, plain ad appeared in the sports section of the New York Times. It had no art, just words:

On the

eve of 1970

please join us

in a prayer for peace.

–Nancy and Tom Seaver

That was as overtly political as Seaver got. A few months later, he made a point of saying that he did not want anyone to change their minds about the great controversy of their times specifically because he had used his platform. “If someone came to the right conclusion about the war because he was emotionally involved with me, the ballplayer, I don’t think that would be right.” He preferred, he said, that someone would get to that point because they saw, “18-year-old young men losing their legs and their lives, about a 4-year-old baby who never saw his father because he’s a prisoner of war.”

He had spoken out before, not in a political way, but just matter-of-factly. He spent one offseason taking undergraduate courses like “argumentation and debate” at the University of Southern California. “I took the view,” he said, “that it’s the wrong war. It’s basically a civil war and a guerilla war, but now we are committed too deeply and at an ungodly cost.”

Seaver’s thoughtfulness was inseparable from his abilities as a pitcher. When he was young he had stuff, command, and control that was as good as that of any pitcher in history. He led the National League in strikeout rate seven times and in strikeout-walk ratio three times. Through his 33rd birthday, he whiffed 7.7 batters per nine. He lost velocity after that, the rate dropping to 5.2 (a shift to the designated hitter league helped), but he was still an effective pitcher. That was because he was also one of the most analytic pitchers of his time. As he said in 1976, “My job isn’t to strike guys out; it’s to get them out, sometimes by striking them out.” He had the stuff of a thrower but the mind of a junkballer, and that was what made him one of the all-time greats. He once said, “I can remember every pitch I ever threw… I never forget those big pitches that give me a key strikeout or a double play.” He was exaggerating slightly—he also took notes—but his emphasis on situational memory and situational analysis, even in his 20s, was real.

The Mets acquired Seaver almost by accident. After his sophomore year of college, the Dodgers selected him in the 10th round of the 1965 draft. Tommy Lasorda did the negotiating for the team and offered $2,000. Seaver asked for something in the high five figures and Lasorda stopped returning his calls. Seaver went back to school. After his junior year, the Braves selected him in the now-defunct January phase of the amateur draft. The Braves took their time about sending a contract, but Seaver did sign. Before that, though, USC played a couple of exhibition games. Seaver did not participate. Nevertheless, a forever-unnamed representative of a team called the commissioner’s office and pointed out a rule that said that no college player could sign once his school’s season had started. It hadn’t, but nevertheless, Lee MacPhail, propping up empty-suit commissioner Spike Eckert, voided the contract.

Seaver might have gone back to college for his senior year, but the NCAA ruled him ineligible because he had turned pro, even though his only pro contract had just been vaporized. The resultant compromise was a lottery, a Seaver-only draft open to any team other than the Braves and the Dodgers willing to match the Braves’ negated bonus package of $51,000. Initially only two teams, the Phillies and the Indians, were interested. Mets scouting director Nelson Burbrink thought Seaver lacked stuff, which tells you all you need to know about old-school scouts. Other members of the front office persuaded general manager George Weiss to participate.

Thus did the Mets, half-hearted entrants in a literal derby, get the greatest player in franchise history out of a hat. When Seaver arrived, the Mets’ all-time leader in career bWAR was Ron Hunt with 8.3. It was soon Seaver, and it remains him as well, with 78.8 wins of an overall total of 109.9. All those wins should have come with the Mets and they could have, but the franchise’s neglect and occasional disdain of a player who was actually called “The Franchise” is a story for another time. This is an occasion for mourning and for celebration.

There is so much to talk about with Seaver that the coming days will require not one remembrance but several, from his iconic drop-and-drive pitching style, which took the stress off of his arms and put it on his powerful legs (he got so low he had to wear a knee pad on his right leg), to signature performances like his record-tying 19-strikeout game against the Padres on April 22, 1970, a game which included a record-setting 10 consecutive Ks. Seaver, again thoughtful, was asked how it compared to his previous most-spectacular performance, the one-hitter (a no-hitter for 8 1/3 innings) he had pitched against the Cubs, the Mets’ rival for the National League East title, the previous July 9.

“This wasn’t quite as exciting,” he said. “It was very exciting, but not quite as exciting as that one.” In later years he would denigrate the 19-strikeout game as having come as the result of unfavorable conditions; it was overcast and cold. “People ask me after a shutout, ‘Was that fun?’ And the answer is no.” Seaver told Frank Deford in 1981. “No, it was not fun. Because fun is such a miniscule word for the satisfaction of what I’m doing… Pitching is far beyond that. I have a sense of satisfaction after a good game, not one of joy. But I’ll tell you what great joy is: Pitching well for an extended period of time, turn after turn. Oh, that’s an extremely good feeling.”

In 1985, on the verge of winning his 300th game, Seaver said, “You reach a point that you can’t go back and reflect on the historical importance of such things because you lose perspective of what your everyday job is.” That’s who Seaver was. He thought critically even about being reflective, and vice-versa. He may have preferred that those who heard him had their minds opened via some influence who was not a professional ballplayer, but he said what was on his mind nevertheless.

Today there is no pitcher like him in terms of his skills and approach, but of late many players have emulated him in public-minded thinking and speaking out. If his example in any way paved the way for today’s players to do so, that’s as much of a legacy as the Rookie of the Year Award, three Cy Youngs, three ERA titles, five strikeout titles, and the rest.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now