There’s been a lot of talk about banning the infield shift at the MLB level, with a rumor that the shift might meet its demise in 2023. If you’re a fan of seeing three infielders on the right side of the infield, you might want to tape a few games from this season so that you can remember what that looked like. The infield shift gets a bad rap for “taking the action out of the game,” assuming that by action you mean “hits.” And there’s some truth to that.

BABIP suffers against the infield shift. We have to correct for the fact that shifting is mostly done against pull-happy power hitters, who also tend to be slow, and so have lower BABIPs, but even adjusting for that, we see that compared to how batters perform against a standard 2-2 defense, the infield shift shaves about 12 points of BABIP overall compared to what we might otherwise expect. The effect is stronger for left-handed batters than right-handed ones. It’s especially tough on ground balls, where I estimate that it shaves 23 points of BABIP. Over time, that’s a lot of hits.

I’m not convinced that banning the infield shift, at least as MLB has proposed in the minor leagues, with a mandate that four fielders be on the infield dirt (or closer) with two on either side of second base, will even restore all 23 of those BABIP points, but it’ll at least do something.

What makes the infield shift such an easy target is that it’s pretty obvious what’s going on. For a sport that spent a century with some pretty strict unwritten rules about “2 over here, 2 over there” seeing a 3-1 formation is a little jarring. But, around 2010, we started seeing the strategy employed more and more. It had previously deployed only against specific hitters (David Ortiz, come on down!), but it grew and it grew and it did not stop. In 2021, the majority of pitches thrown to left-handed batters were in front of an infield shift. It was as much an aesthetic assault as it was a move toward defensive efficiency.

It’s widely known what happened. A few years after Moneyball, most teams got savvy about data and started asking questions like “If the batter isn’t going to hit the ball toward third base, why station someone there?” Instead, let’s put a third infielder on the right side. A little #GoryMath showed that it improved outcomes, but critics pointed out that it improved outcomes in the same way that spreading manure all over a field improves crop yields. It stunk, but it stuck, and it stuck because it worked. At least, it worked for left-handed hitters.

If there’s a storyline to watch over the next few years, it’s going to be Major League Baseball’s re-shaping of itself. For a long time, MLB has taken a fairly laissez-faire approach to the evolution of the game on the field. Ideas like pitch clocks, long decried as against the “timeless” spirit of the game, are being tested at the minor-league levels, with indications that they too will be seen in a major-league ballpark near you sooner than later. If they do nothing else, they do speed up the pace of the game, even if they make people mad who believe that the game should be played the exact same way it was in 1950.

But MLB doesn’t have an agenda in whom it plans to offend. If MLB does ban the shift, it would be banning one of the most visible signs of the “new age” movement in the game. The data nerds found a place where the game wasn’t being played efficiently, and with nothing stopping them, made it more efficient, if less entertaining.

There’s a key word in that last paragraph. Visible.

Warning! Gory Mathematical Details Ahead!

Let’s talk about the shift. Not the infield shift, and no, not that one either. Or even that one. The one that no one ever talks about. The invisible one. The outfield shift. And no, this isn’t the one about the fourth outfielder.

You didn’t notice that they were shifting out there? My colleague Rob Arthur did. Last year, Rob pointed out that outfielders were playing deeper and that defensive positioning is taking away hits from batters, and that teams were indeed being specific about their outfielder placement..

They’ve been doing it for a while. And here’s what’s happened:

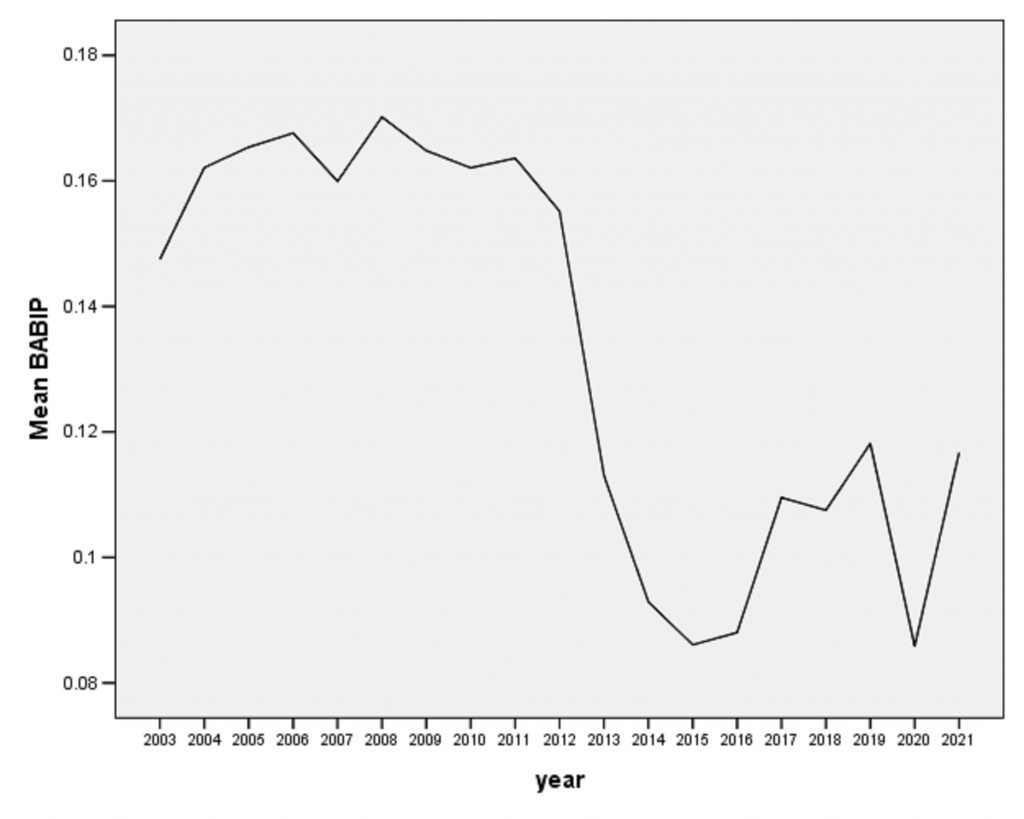

This is BABIP on fly balls to the outfield. We can see that it was pretty stable from 2003 to about 2010, holding steady around .160. In 2011, around the time that teams started ramping up their infield shifting, outfield BABIP also started dropping and by a lot. From 2010 to 2021, we can see a drop of about 50 points(!!!) of BABIP. One can only imagine that they were applying the same principles of stationing fielders where the ball was likely to be hit in the outfield as well.

Can you honestly say that you noticed? For one, a fly ball to the outfield has always been a good candidate to be caught. Even in the dark ages, five of every six of them ended up in someone’s glove before hitting the ground. On top of that, you still had a left, center, and right fielder out there. They just moved a few feet here or there to areas where the ball was more likely to be hit. The data nerds figured out how to position the outfielders more correctly, and the result is as plain as day.

Remember earlier when I said that the infield shift suppressed BABIP by about 12 points when it was employed (and against ground balls specifically, by about 23 points?). Well, the effects of better outfielder positioning are four times as powerful at taking away hits. More than that, not everyone gets shifted, but everyone hits fly balls. Better, data-driven, outfielder positioning is taking away far more hits than the infield shift.

Perhaps the rise of the infield shift actually caused the decrease in outfield BABIP? After all, the standard story is that hitters see the shift and try to launch the ball over it. Maybe they’re being goaded into easier fly balls? Nah.

Above, I suggested that the effect of the infield shift on ground balls was 23 points of BABIP. I got that by looking at grounder BABIP for individual players when they weren’t being shifted. If a batter had a .250 BABIP on GBs without the shift, and the shift made no difference, then we would expect a .250 BABIP on worm burners in front of the shift. For one individual player, there’s going to be too much noise, but if we sum across the league, we can get an idea for the effects of the shift as a strategy.

I did the same thing, but with fly-ball BABIP. While hitters lost 23 points on grounders, they actually gained a tiny bit (tiny enough that the effect is basically nil) on fly balls hit in front of the infield shift. It’s not the infield shift that’s driving down outfield fly ball BABIP. It’s just that teams are better at positioning their outfielders.

Now, MLB has a bit of a decision to make. They’re already considering legislating where the infielders can stand. Will they do the same for outfielders in the name of restoring “action” to the game? They could mandate three spots in the field where outfielders need to stand as the pitch is released, and they could be the same for all batters. For some, they’d be in the “wrong” places.

Doing that would do more than banning the infield shift ever could to bringing more hits into the game, so if they want to inject more action, that’s the place to start. It’s a question of philosophy. Is the point of the coming Great Baseball Makeover going to be to restore some classic aesthetic to the game or is it to gently guide the types of outcomes that the game produces? If we’re going to ban things, not because they provide an untoward advantage, but because the fans find them annoying in some way, then we need to ask what criteria we’re going to use to ban them.

If the #NewMoneyball is having your innovations fly under the radar so that people don’t complain about them, it would be nice to know that.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now