When I was younger, I was (you’ll be shocked by this, I’m sure) fascinated by space. I learned about the planets and their orbits and their names and their colors (and I learned that there were nine of them—oops). Among my prized collection of space-themed t-shirts was one from the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, which depicted the planets in their orbit around the sun. I loved looking at that shirt and picturing the planets as they moved throughout their orbits. And I learned about distant stars and how they worked and what the constellations were.

Now. Learning about the gasses that make up the atmosphere of Venus (hint: if you are ever on Venus, BRING AIR) is pretty cut and dried; it is objective. Learning that it’s called Venus and that it’s a planet is somewhat less so (especially now that there is now some actual controversy over what, exactly, is and isn’t a planet). But it’s a discussion grounded in fact, where the disputes are largely about how we express the reality, not the underlying reality.

Constellations, however? Constellations are not intrinsic to the stars themselves. Let’s take the Big Dipper. Of course, it doesn’t have to be called that—in Hindu astronomy, for instance, it’s called the “Seven Great Sages,” after influential figures in the Vedas. In Hungary, it’s called the Göncölszekér and is thought not to be any kind of a spoon but in fact a mythical cart. It is mentioned in the Bible and Homer’s Iliad.

What’s fascinating is that in so many cultures, those seven stars have taken on a special meaning, even as that meaning varies between time and place. But the grouping of those seven stars together has far less to do with them and much more to do with us. The closest of the stars, Mizar, is 78 light years away; the most distant is Dubhe, at 124 light years away. That’s a difference of 46 light years. To put that into some perspective, the closest star to Earth other than our sun is Proxima Centauri, which is roughly four and a quarter light years away. Proxima Centauri, it should be noted, was not discovered until 1915—it requires a telescope to even see it. The stars comprising the Big Dipper are of course much brighter (we can see them even from here), but if we were standing on a planet in orbit around Mizar, there’s nothing to suggest that we would realize that we had any sort of a kinship with Dubhe; it might very well appear to us as just another star in the sky.

Constellations appear because there are many stars in the sky, and because our brains are wired to seek patterns and to impose them upon what we see. Once we’ve named the Big Dipper, it’s obvious that those seven stars out of the thousands in the night sky are significant. But that’s an imposition we’re making on the sky.

Just how many stars are there? Well, that depends on a lot of factors:

On a clear, moonless night in a place far away from city lights, you should be able to see about 2000 stars. The darker the skies, the more stars you can see. Astronomers have calculated that there are about 6,000 stars potentially visible with the unaided eye, of course, there’s no way you could see them all at the same time. Some stars are visible from the southern hemisphere, while others are visible from the northern hemisphere. Some stars are visible in the summer months, while others are visible in the winter months.

But overall, something like 2,000 stars at a time.

By contrast, looking at the Palmer database of baseball, there have been roughly 17,500 players who have ever played Major League Baseball—that’s hitting, fielding, and pitching. There have been almost 200,000 games (and double that when you consider that there are two teams per each game), and nearly fourteen million at-bats. The scope of the observable universe of baseball is far larger than the scope of the infinite expanse beyond our world that we can see with the naked eye.

And at such great magnitudes, it becomes difficult to comprehend the enormity of it all at once. So we break things down, impose order on it, and try to make it manageable so that we can comprehend it.

So let me tell you a little story, and then let me break it down for you. Roughly a decade ago, I was a combat correspondent for the I Marine Expeditionary Force. At the time, I was assigned to do a story on how local police were being empowered to fight crime and preserve order. So I was doing ride-alongs with the 372nd Military Police Company, an Army Reserve unit out of Cumberland, Maryland. (Since the whole point of this story is wild coincidences, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention this little aside. Some time later I would be at Abu Ghraib prison, doing a story about Marine security guards and how they were handling the response to the revelation of the abuse that had occurred inside the prison. And sure enough, while going over my notes for the story I realized something—that the MP company I had been doing ride-alongs with had been from the same unit that was responsible for those abuses, and that it was in fact plausible that I had met some of the MPs responsible for them.)

We were patrolling a region south of Baghdad in the vicinity of Al Hillah, which by comparison to a lot of areas was relatively peaceful. So whenever we would be on patrol, we would attract a fair amount of sightseers, mostly children looking to see what was up and whether the soldiers and Marines would give them candy and bottled water and such. (And often we did, although command stressed that we absolutely should be doing no such thing while on patrol.)

I remember one group of three kids, standing in a doorway watching us moving slowly through the street. And what I remember more clearly than anything was the boy in the front of the trio, wearing a t-shirt from the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, which depicted the planets in their orbit around the sun. The same one, in fact, that I had worn when I was younger.

Now what are the odds of that happening? Pretty low. But here’s the thing. The odds of that exact event happening are low. But that’s also why it’s memorable. What I don’t remember with anywhere near the same clarity is all the perfectly ordinary things that happened, and what I have no recollection of at all is the improbable things that didn’t happen at all. Because probability isn’t what we see—in the world that we observe, things either happen or they don’t happen. If you live long enough, all sorts of improbable things will crop up. And those moments are what we’ll remember, and when we go through the vast expanses of stars in our lives, they will shine the brightest when we look to make constellations out of them. And we call those constellations narratives.

This may have gotten me into a little trouble recently—not the actual sort of trouble with terrible consequences, but the fun sort of trouble where I get into an amiable spat with a national sportswriter on Twitter. Jeff Passan of Yahoo! Sports wrote a column about the Yankees’ dismal showing in the ALCS through the first two games, saying:

No, it's not easy playing when a support system turns so vociferously. Yeah, well, it's not easy being asked to support a team that performs so badly at the most important time of the year, either. The Yankees are staring into a deep abyss. Their core keeps getting older. Their pitching woes remain palpable. Their farm system – especially the upper-level arms that were supposed to be here by now – has dried up considerably. It's not like Jeter's injury was some sort of sign. It was just a reminder of what was – and what is no longer.

Jeter represents the era in which the Yankees could do no wrong. They won so much only a contrarian could view the franchise with cynicism. Those Yankees earned every ounce of pride.

It's easy to wonder how much of this traces back to the passing of George Steinbrenner, their bombastic owner. While he presided over more than a decade of misery that preceded the late '90s dynasty, his presence throughout the winning cannot be overstated. The culture under Steinbrenner was about the team. The culture today is about the business. Yankees fans loved Steinbrenner. Yankees fans don't know his sons. The urgency then was palpable. The urgency now is questionable.

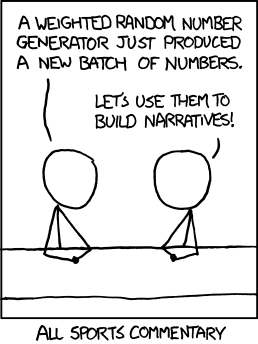

In response, I tweeted a link to this XKCD cartoon to Jeff (never let it be said that I do not buy my own trouble):

So, yeah, I pretty much deserved whatever I got in response. And what I got was this:

@cwyers The proliferation of the word "narrative" is the single worst thing to come out of the stat crowd since defensive metrics.

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) October 15, 2012

@cwyers It's so easy to reduce something to that single stupid word. It's lazy. And of the many things you are, lazy isn't one of 'em.

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) October 15, 2012

I think the size of this column so far is an indicator that yes, I am not lazy. And we’ll leave Jeff’s claims about defensive metrics for now, because this is already long and rambling and my opinion on that topic is not inaccessible. So let’s focus on the main contention, that sabermetrics has introduced this idea of “narrative” to the discussion and that we’ve cheapened the discussion by doing so.

I don’t think the idea of narratives in baseball writing is one advanced primarily by sabermetricians. And I don’t think it’s really disputable that they exist, or that there is a class of people (primarily beat writers) who regularly use narratives. Narrative, after all, is another way of saying “story,” and there’s a reason that what reporters write are called stories. It is probably true, though, that sabermetrics has turned “narrative” into an epithet.

I don’t think that all narratives are bad. I think that on the whole, narratives are necessary for discussion about baseball. Narratives can be used to help communicate complex things, to entertain, to enlighten and to amuse. Narratives are a lot like cars—they are extremely useful, they can occasionally be dangerous, and they have some subtle, diffuse effects that we may not even be aware of.

So let’s examine some other narrative accounts of the same events that Passan reacted to—Game Two of the ALCS, and all that was attendant to that. Let’s start with the New York Daily News:

The Yankees’ big hitters looked awful once again, as Robinson Cano, Alex Rodriguez, Curtis Granderson and Swisher combined to go 2-for-14 with seven strikeouts.

“We know what they are doing to us; we have to make adjustments,” Joe Girardi said. “They are not going to put it on a tee for us. We know that. We are more than capable of scoring runs, and have done it a number of times this year. We have to make adjustments.”

The Yankees made no such adjustments during the game, going 0-for-5 with runners in scoring position and stranding seven. Fans responded with a chorus of boos for most of the day, letting the players know what they thought of their performance.

“You can’t blame them,” A-Rod said. “We have the ability and a lineup that’s equipped to score a lot of runs and we got shut down today.”

Here, the narrative context is simple—the Yankees didn’t do what they needed to do to get hits when they needed them. Let’s switch over to the Detroit Free Press:

Yankees right-hander Hiroki Kuroda summoned the heritages of some terrific postseason pitchers Sunday as he mowed down the Tigers.

Through five innings, the Tigers didn't have a baserunner against him. But the Yankees, thanks to Anibal Sanchez's tenacity and pitch variety, didn't have a run.

"Anibal matched Kuroda pitch-for-pitch," catcher Alex Avila said. "He's a bulldog."

In the seventh, the Tigers broke through for the first run. They added two in the eighth after an inning was prolonged by an umpire's missed call. Phil Coke relieved for the eighth, stayed around to fill the Jose Valverde void in the ninth, and finished off Sanchez's 3-0 win. In the last four games, the only Tigers pitcher to allow an earned run is Valverde (who has given up seven in that time).

The Tigers come home with a 2-0 lead in the best-of-seven championship series. The torrid Justin Verlander will pitch in Game 3 against the frigid Yankees, who have many big-name hitters way overdue to break out. If the Tigers win Game 3 with Verlander, the only way the Yankees can take the series is to win the next four games, capped by a Game 7 started by Verlander.

Here, the narrative is less about hitting and more about pitching—it acknowledges that Kuroda had a good performance, but insists that Anibal Sanchez matched him through “tenacity and pitch variety” to provide the Tigers with the win. And here’s a perspective from national writer Dayn Perry:

Is it too much, too absolute to say that Jeff Nelson's call at second base in the eighth inning cost the Yankees Game 2 of the ALCS? Indeed, it is. But it may have hastened baseball's methodical, meandering march toward expanded replay.

To set the scene, Omar Infante was on first following a two-out single. Austin Jackson then notched a base hit to right. Nick Swisher fielded it cleanly and gunned to second base to cut down Infante, who'd strayed too far while thinking of going first-to-third. Swisher's throw beat him by a margin measurable in yards, Robinson Cano tagged him on the chest and Nelson's call was …

Safe? Safe. "The hand did not get in before the tag," Nelson admitted after Game 2. "The call was incorrect."

As a consequence, the Tigers' second run of the game scored, and they went on to plate another after what should have been — what really was — the third out of the inning. The Yankees, of course, failed to score, so their primary complaints about the outcome of Game 2 should be directed at their hitters. But it was an obviously blown call that, given a competent Yankee offense, could have turned a win into a loss. The obvious question, now that such a play has occurred under very conspicuous circumstances, is whether Nelson's call will advance the cause of expanded replay in MLB.

Here, the narrative is about the umpiring, and a blown call that could have been critical. Dayn is too good a writer and too sharp a thinker to attribute the whole of the loss (and victory) to the call, but he does make it the emphasis of his narrative about the game.

So, to review:

- All of these are constructed narratives—they are the stories these writers are telling about this one ball game. While all of them have the game in common, they all are able to find different narrative threads for the same game. One game can have many storylines to it.

- Baseball seems to readily lend itself to at least two storylines per game—one for the winning team, one for the losing team. It’s possible to have more than that, but at the very least you tend to see those two narratives to a game.

- If you distill a game down to two stories like that, you’re getting an incomplete picture. There is an ancient proverb among my people: “Understanding is a three-edged sword.” There’s your side, my side, and in the middle there is the truth. Did the Yankees hit poorly? Did Sanchez pitch well? From a particular narrative viewpoint, one or the other seems more prominent—but from a distance, they both seem to blend together. We don’t need to decide between one or the other, but we can have a gray space that encompasses both.

- But even if each narrative is incomplete on its own, that doesn’t mean it cannot be useful, entertaining or instructive.

In particular, the team-centric narratives have as their purpose to impart the sense of the game in a limited space to a fan of the team, usually. No doubt Yankees fans and Tigers fans had very different feelings about the game as it progressed—each of them has a different view of which team is the protagonist and which is the antagonist. So to that end, those narratives do what they’re supposed to.

That’s one use of narratives in sports, and (I want to say this again to make sure that it’s not missed) a useful and important one. There are others. Remember, again, narratives can be used to entertain, inform, persuade—the key point is that narratives are a useful tool in communication. And I should note that sabermetricians who wish to be able to communicate thoughts and ideas to others would do well to learn how to use narratives. (This column about narratives contains several narratives, in fact.)

There is a level at which we can appreciate narratives for their own sake, but at a deeper level narratives are like anything else we use to communicate (infographics, mathematics, raw data even): they are only as useful as what they are attempting to communicate. A well-crafted narrative in service of espousing a bad idea is a narrative that can range anywhere from unuseful to actually damaging.

Building a sports narrative is usually not an act of creation but of selection and arrangement—using parts of the whole in such a way that they conveys a sense of a whole thing. So if we want to examine sports narratives, we have to ask: Why emphasize these things? Why exclude these other things?

To my mind, the worst sports narratives—the ones that do a disservice to fans and writers and the participants themselves—are the ones that, so to speak, try to make sporting contests primarily about character. To be blunt, there are plenty of good, decent people in the world who would make terrible professional athletes. And by the same token, there are plenty of people in the various Halls of Fame of American professional sports whom few of us would ask to babysit our children. Making sports about character can frequently lead to poor discussion about sports. More importantly, as becomes very apparent when we try to have discussions about actual character issues in the context of sports, it does a lot of damage to our ability to discuss character and morality and the like when we confuse it with the sort of things that allows people to win sporting contests.

So let’s return to Passan’s column, where he calls the Yankees out for looking like a bust:

No wonder Game 2 of the ALCS featured thousands of empty seats, like Game 1 before it, and like the do-or-die Game 5 of the ALDS, too. New Yorkers understand a fraud when they see it. They pay for expensive seats, drink overpriced beers, buy exorbitant merchandise and fund a $200 million joke, a team that for the second straight game couldn't score a measly run off the Detroit Tigers' Nos. 3 and 4 starting pitchers. These Yankees earned every last boo.

The vitriol that has evolved here over the last week apexed Sunday with a 3-0 loss in which Robinson Cano extended his record playoff hitless streak to 26 at-bats, Curtis Granderson struck out three more times in three at-bats and Alex Rodriguez whiffed twice. Something is different here. Very different. Not only are the Yankees searching for their identity with a series deficit of 2-0 and three games beckoning in Detroit, their ravenously loyal fan base is revolting against an old, overmatched, passionless team.

Passan goes on to comment on how this is “a stunning indictment on their failures to transition the atmosphere of the old stadium to the new one” and asks “how much of this traces back to the passing of George Steinbrenner, their bombastic owner.”

There are many truths—the Yankees are losing games to the Tigers, they are an aging team, etc. There are some things that may be true that we’ll concede for the sake of argument, like the notion that the empty seats in Yankee Stadium are a recent phenomenon. (Published attendance figures are usually based on ticket sales, while the so-called “turnstile” numbers that reflect actual attendance at the game are typically more difficult to obtain.)

But does it all hang together? If we define the Steinbrenner era as 1973 through 2007 (when he formally handed control of the team over to his sons Hank and Hal), we see a team that won at a .563 clip during the regular season; the post-George Yankees have won at a .591 clip so far. Ah, but what of the postseason? The Yankees made the postseason in eighteen out of 35 of those years, compared to four out of five of the post-George years. Ah, but the pesky wild card muddles the picture. Still, the post-George Yankees have won the division three out of five seasons, compared to 15 out of 35 in the George era. And what of the ultimate prize, winning the World Series? The Yankees under George did that 17 percent of the time, compared to 20 percent of the time for the post-George Yankees (and that’s if we assume the Yankees do not win this year, which seems likely but far from certain at this point).

Now, Passan is careful to mention the '90s dynasty of the Yankees, but it seems a woefully unfair comparison if we consider only George’s successes and ignore his failures (if that dynasty can even be considered something he accomplished, rather than something accomplished in spite of him). What can be said of this year’s Yankees is that they have the best record in the tougher league, that they won their division, and that they beat the Orioles to advance to the next round of the playoffs (remember, the wild card cuts both ways—many of Steinbrenner’s teams never had to face a five-game elimination round before the championship series.) Yes, they may now be eliminated by the Tigers in the ALCS, but that sort of thing happens to good teams—in fact, can happen only to good teams. And it was a George-era Yankees team that suffered one of the most humiliating ALCS losses ever, allowing the 2004 Red Sox to overcome a three-game deficit in a best-of-seven series.

Turning two defeats to a division-winning team like the Tigers into an indictment of the entirety of the post-George Steinbrenner Yankees ignores much of what we know about the 2012 Yankees, does a disservice to the whole of the history of the Yankees under the Steinbrenner family, and—perhaps most gallingly—treats the Tigers as mostly incidental to their own success. That may be appropriate for something like the Daily News, but national coverage should aim to do better than to simply take on the point of view of any one fanbase, no matter how large the fanbase is.

Is it fair to lay all of that at the feet of narrative? No. But it’s the sort of thing that happens all too often when we try to express simple certainties about complex realities. Narratives are useful in simplifying complex things so that we can understand them better, but we have to be careful that we aren’t simplifying things to the point where they no longer do a good job of representing what it is we’re talking about.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

People are meaning making machines."

1) Something happens.

2) We observe it.

3) We attached meaning to our observations.

4) Repeat.

The more we advance technology, the more we we can parse our observations into more discrete granules. But that doesn't change any of the other steps in the process.

This is the story of our lives.

We stand on the bridge, and no one may pass.

We live for the One, we die for the One."

First, I agree with the statement that narratives are critical for explaining complex ideas to the masses. As fascinated as I am by the theory behind sabermetrics, the narrative aspect is why I read Baseball Prospectus every day but struggle to make myself an avid reader of The Book Blog. To me, The Blog is like an academic journal while Baseball Prospectus is more like Popular Mechanics. In both pubs, the authors clearly understand the deepest details of subject, but in only one do they try to relate those details in a way that is palatable for interested parties who don't have Masters Degrees.

It's hard to overlook how important Narrative is to baseball and baseball writers, because baseball is a game that even the most dim-witted fellows in America can enjoy. Thus, a discussion of baseball stats without narrative becomes unreadable for 99.9% of the audience (full disclosure: that's a made-up stat).

It's really easy to point out that Yankee-Bashing, umpire praising, and Anibal-loving is oversimplifying something that can be described as a complex system, but the truth is that if professional writers (those guys who do nothing but cover the sport on a superficial level) tried to include all narrative aspects of an event in their stories, they'd completely lose their short-attention audiences. Your article is 4,020 words, but you probably couldn't have gotten away with such a digression-laden story (albeit very pointed and entertaining digressions) when writing for a newspaper or major media outlet like Yahoo.

So, while I agree with what you say in this article and am no fan of Passan's passive-aggression towards anybody who disagrees with him, I personally feel that narrative is critical if sabermetricians want to achieve their real goal, which is widespread adoption of statistics that MEAN something.

(By the length of this comment, it's pretty obvious I would make a terrible newspaper columnist because I tried to cover all my points rather than focusing on one zinger like Passan did in his article.)

As for Passan, I don't have a problem with him personally; he and I have been e-mailing back and forth amicably since this came out. I think it's healthy for everyone involved if we can have discussions and even disagreements while still being friendly about the whole thing.

Saying "that was unlucky" or "that was really unlikely" is seen as woefully incomplete, and the mindset of someone who's just not thinking hard about things. I see this from saber-leaning people too, where game-to-game variation in average velocity isn't about the park, pitch fx calibration, or randomness - it's about an approach, or pitching to contact, or trying to work deep into a game.

Ultimately, I think most people prefer writers (and interlocutors at a bar or at the water cooler) to expound on "what it all means." I wouldn't consider it a failing if a beat writer focused on specific calls, decisions, and plays in a game in lieu of imputing character traits to small-sample results, but I also think that beat writer wouldn't have his job for long.

With that said, I completely agree with that point and wish more writers and editors would look further than the prose for whether or not an article is worthy of an audience.

It's a preposterous bit of navel-gazing that Red Smith, Vin Scully or Jon Miller would never use. They use artistry to set up narratives for a game. Too many other broadcasters today are like bad magicians who can't help but reveal their tricks as they perform them, ruining the experience for the viewer.

Go ahead and set up the game. Describe the storylines. Alert us to what's been happening that's led up to this game. That's important. Just please don't be so hacktastic (term works for hitters and "journalists," both) as to have to use the term storylines to set up the storylines. Next we'll find writers and broadcasters using the term "narrative" in their stories and broadcasts. Hack, hack, hack, you're out.

I'd argue that statistical analysis of baseball wouldn't be the least bit interesting if it yielded no narratives. The best work of the stat community has been not only in exploding false narratives but in creating new ones that are supported by data. Is "narrative" really different from "conclusions?"

Without narratives, stats are just trivia.

For example, we have ample evidence that Daniel Descalso, in real baseball games at real times that matter, succeeds less than often than most players. We have 838 plate appearances of them. When he gets a big hit against a team in the playoffs, do not write a story about how his grit let him succeed. If that is true, where did his grit go all of the times we've seen him fail? Will this magical grit of his be there tomorrow? Is it something he magically developed just for one game? Could he somehow use this grit more often to become a league average hitter, or can he only use it one post season game a year?

I understand that we'd like our heroes to be special, and some writers know the players and would like to believe good things about them. But this is simply poor writing.

One thing that I wonder about is how can we expect sportswriters to resist the temptation to proliferate the narratives demanded by their audience? What's the incentive for change?

I tire of not just the character-driven narrative stuff but the elevation of symbols over substance - the AL MVP award seemed like a bigger story down the stretch than the actual pennant races. This, it seems to me, is all about reader psychology.

I'm all for trying to educate the audience and trying to expose them to new ways of thinking, but as long as the Holliday/Scutaro incident (conflict = drama) is getting the page clicks, traditional narratives will prevail. I'm not that confident that this is a generational thing that will abate with time.

I don't mean to sound like a downer - I guess I'm just accustomed to intelligent analysis being a niche product in the media world we live in, whether sport, politics or business.

Great article. It is fascinating that sports so often has narratives that support that which we so much want to believe. Other than war, I can't think of anything where story lines can be so divergent, depending on the point of view of the individual. We invest greatly in things that we wish to believe.

The only area is which writing is infinitely worse is politics.

Brilliant takeaway point that extends far beyond baseball and into nearly any realm you can imagine.

Passan's calling Fister and Sanchez no. 3 and 4 starters is a great example of twisting near facts (arguably they are better than Scherzer) to create a bogus narrative. Fister and Sanchez would be no. 1 starters on most teams as indeed Sanchez was for Miami.

George Steinbrenner is dead, but according to one high up front office Yankee recently, they are still trying to live up to his "anything less than the championship is failure" credo. I find that attitude repulsive - and feel sorry for all the Yankee fans who share it. There won't be much joy for them - and from the look of the current Yankees - there is some truth in Passan's overall point if you take a longer view in that the Yankees are a very old team without much in the way of minor league talent on the way to revitalize themselves - it will likely be a long time before their next championship.

You can extend this argument into Yankee-land even further. Which player is better, Derek Jeter or Alex Rodriguez? Both are still playing so the target keeps moving, but imagine after their careers that A-Rod whips Jeter by a long shot in terms of WARP, win shares, however you want to measure it. Will A-Rod ever be considered the better player outside of a circle of stats devotees? Probably not, and all because the narrative that has been built around him is about failure, while the narrative that has been built around Jeter is all about winning. The narrative that maybe once-upon-a-time had its roots in stats, or at least in some of what actually happened on the field, has grown to be largely unrelated to any actual facts. Narrative can stray so far from the facts as to become fiction.

A beat writer's job is essentially to create a narrative. Following the New York writing corps Twitter feeds you could see them straining to shape a story, the way Carlton Fisk once tried to body-english a home run. Fisk's dance didn't actually affect the flight of the ball, and beat writers Tweeting things like "Does the A-Rod redemption train finally get on track with this at bat?" didn't actually help A-Rod do anything, but if he had done something like hit a game-winning homer , there would have been a slew of redemption-story narratives the next morning.

All of which is a long-winded way to say, I absolutely agree. Every fan is writing a story in his or her mind every game, every season. Our investment in the outcome of the story is what makes us fans of a team or a player, and not merely connoisseurs of athletic prowess.