At the end of May, I introduced the idea that some teams were going from playing nearly straightaway to using a full overshift once they got two strikes on certain pull-heavy, bunt-threat lefties. The idea was that teams would probably prefer to implement a full overshift earlier in the count, but were hindered by the hitter’s ability to bunt for a base hit. This was inspired by the Orioles using a two-strike overshift numerous times against Michael Bourn, and the Pirates doing it a couple of times against both Denard Span and Danny Espinosa.

The next week, the Yankees tried out a pair of two-strike shifts against Coco Crisp during the first game of a three-game set in the Bronx against the Athletics. However, the Yankees stopped using the two-strike shift against Crisp after that first game, which I hypothesized was because Crisp beat the shift by slapping a single where the shortstop had been playing previously. New York didn’t use a two-strike shift against Crisp when they traveled to Oakland for a three-game series the next week either.

Oakland’s next series after the one in New York was in Baltimore, which at the time looked like the perfect environment for another two-strike shift to brew. The Orioles had not only utilized the strategy against Bourn, but they had just used it against Leonys Martin during the previous series (they have since used two-strike shifts against Brock Holt and Kevin Kiermaier). However, the Orioles played Crisp straightaway during all two-strike at-bats during that series.

Fast-forward a month and a half to this past weekend at O.Co Coliseum, when most baseball folks were wondering what type of fireworks would be set off in the first meeting between the Athletics and Orioles since last month’s unwritten rules debacle starring Manny Machado. I, on the other hand, pondered how Baltimore might align its infield against Crisp. After all, the Orioles have led the charge in shifting against speedy left-handed pull hitters, and there’s a precedent for a two-strike shift against Crisp, who has 69 career bunt hits but also pulls a steady diet of his groundballs to the right side of the infield.

Crisp flew out on a 2-1 offering from Chris Tillman during his first trip to the plate on Friday. The Orioles had their standard infield alignment in place, with Machado predictably playing in on the grass.

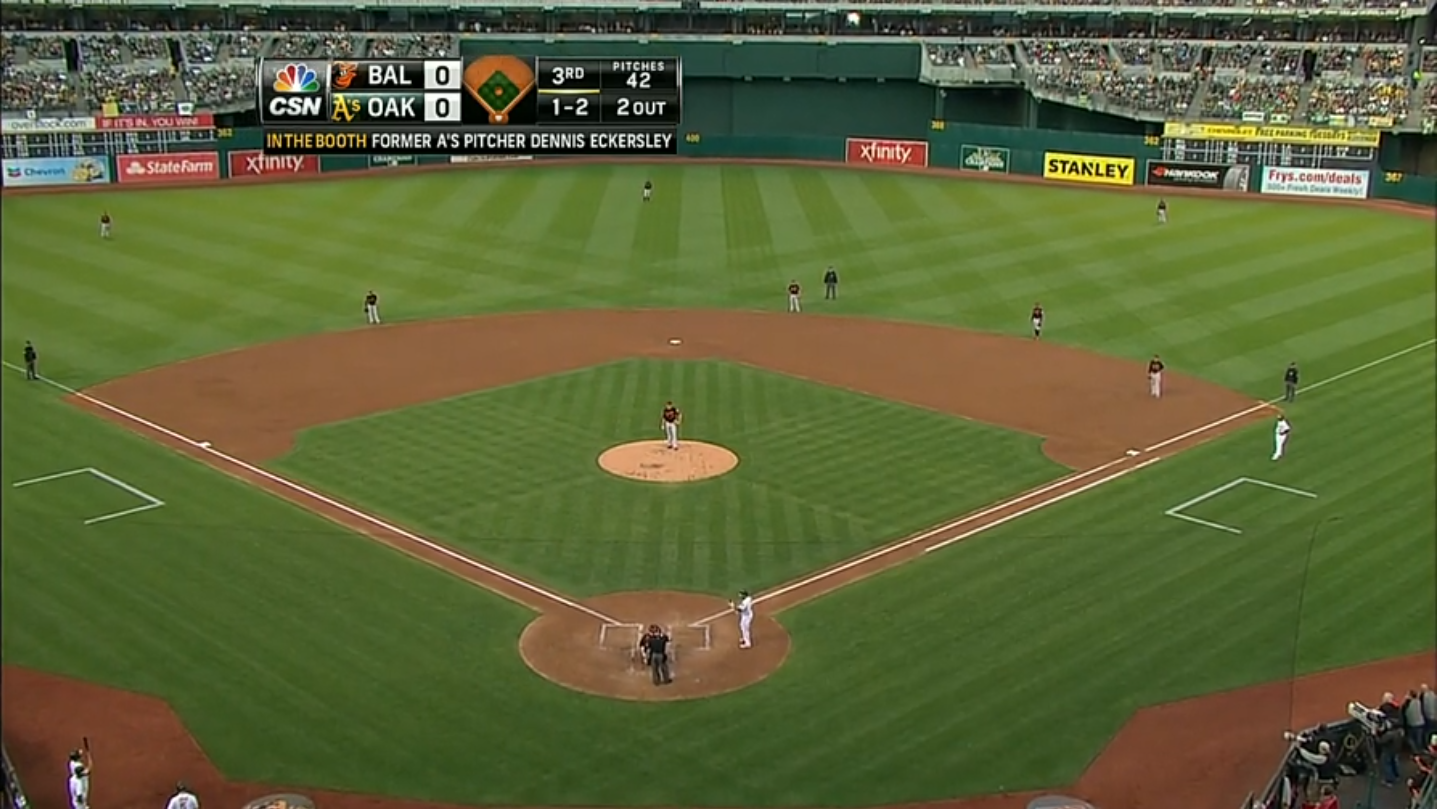

In the third inning, Tillman broke off a 1-1 curveball to Crisp to dig him into a two-strike hole. Immediately afterward, you can see J.J. Hardy walking from the shortstop area toward the other side of second base. Keep your eye out on the bottom of the clip below.

And there we have it! Baltimore’s first full overshift used against Crisp.

Crisp proceeded to lace a single over the shift into right field and received the same treatment during his next at bat against Tillman, in which he worked a seven-pitch walk.

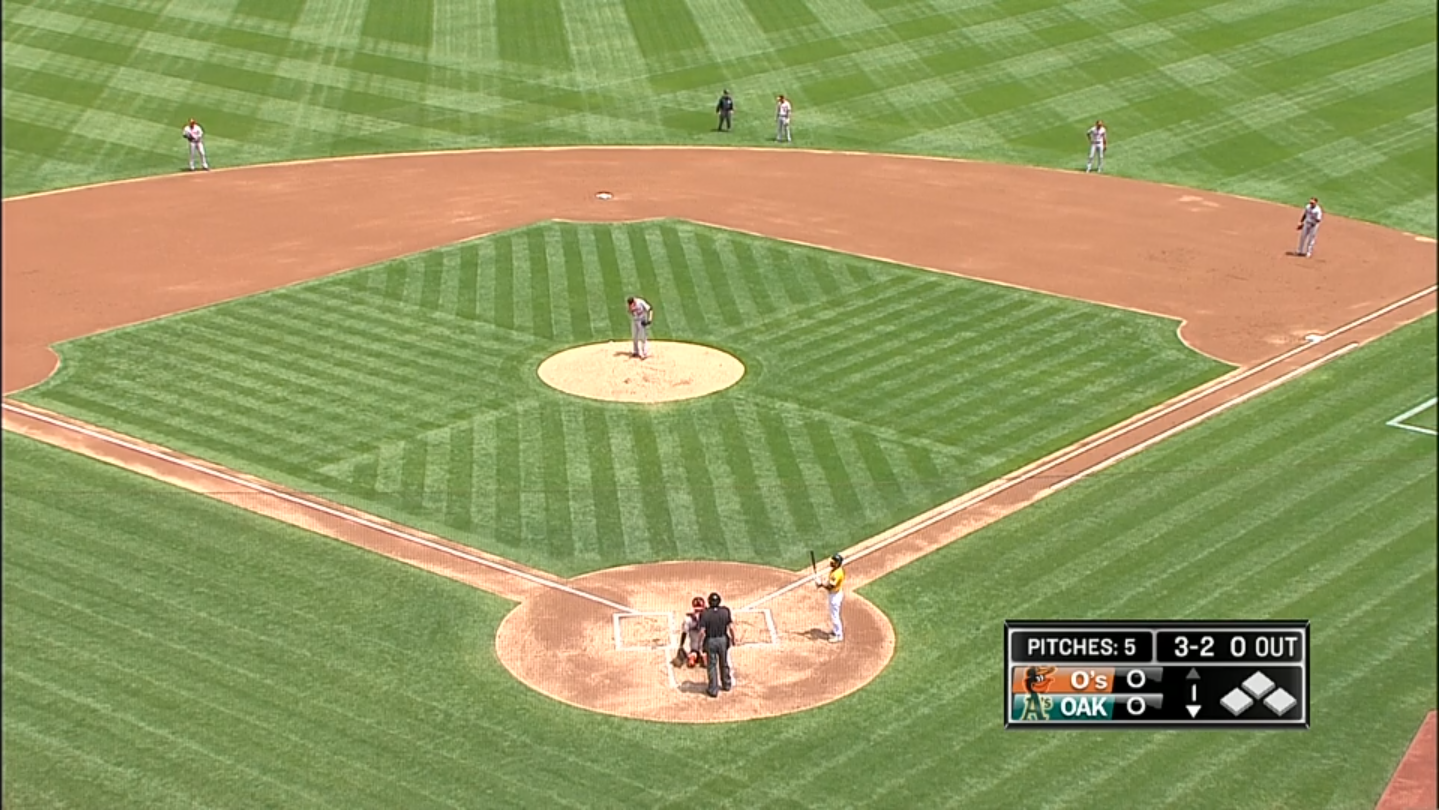

There was one more instance in which Crisp stared down a full overshift this weekend. On Sunday, Crisp led off the bottom of the first inning against right-hander Kevin Gausman and tried to sneak a bunt down the third base line with a 2-1 count.

Neither broadcast provided a clear view of where Machado was positioned prior to Crisp’s bunt attempt, but immediately after, MASN play-by-play man Gary Thorne said, “He did have Manny Machado backed up there. Manny played in on the first couple of pitches then moved back after the strike, and he’ll stay back now with the count at 2-2.”

Machado not only stayed back (he was presumably a few steps back off the grass), but he moved all the way over to the normal shortstop area, as Baltimore’s infield alignment completed the drastic shift from this…

…to this.

Those who joined the Baseball Prospectus crew in Oakland on Saturday night did not get to witness any full shifts used against Crisp, as the Orioles sent southpaw Wei-Yin Chen to the hill and did not use any full overshifts against Crisp when he batted right-handed during the series. Defensive shifts against right-handed hitters have become more prevalent during the past year or two, so I was initially curious why Baltimore didn’t shift against Crisp when he batted from the right side. After all, his hit tendencies as a right-hander are just as pull-heavy as they are when he bats left-handed.

While Crisp’s spray chart from either side of the plate suggests that he is a shift candidate, it doesn’t scream "Ted Williams shift" the way that David Ortiz’s or Brian McCann’s does from the left side or the way that Albert Pujols’ or Jose Bautista’s does from the right side. Crisp still manages to slap some balls the other way, which makes an effective full overshift against him contingent on whether the infield defense can still prevent opposite-field groundballs from going through.

From either side of the plate, Crisp rarely goes to the opposite field down the line. As a lefty, he’ll hit the majority of his opposite-field grounders to the shortstop area, and as a righty, his groundballs to the right side of the infield are usually hit to the keystone.

With Machado roaming his former stomping grounds at shortstop, a full shift against left-handed Crisp makes perfect sense for the Orioles; they get an extra fielder to defend the right side of the infield and the area that Crisp most often hits his opposite-field worm-killers is properly defended by Machado.

A hypothetical full shift against right-handed Crisp wouldn’t be nearly as effective for Baltimore. Instead of having Machado playing deep to defend all that open real estate, Baltimore would have Chris Davis playing much more shallow and closer to the line in order to allow himself enough time to cover first base. Not only does Davis clearly lack the range that Machado possesses, but he would also be at a further disadvantage because of his positioning.

The Orioles have the advantage of essentially having two shortstops man the left side of their infield, which allows them to deploy full overshifts against left-handed batters with the confidence of knowing that they have a Gold Glove caliber defender protecting the left side of the infield. That advantage effectively disappears when Crisp bats from the right side.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now