The batter read the spin of the pitch: slider. It came straight at him, but he knew it was a ruse, that the pitch was going to break back toward the plate, bite the back corner, and strike him out. He held firm. It was a breaking pitch, 86 miles per hour, but it seemed to take forever. The batter started a check swing he hoped he wouldn’t need. But the pitch didn’t break, and clipped the elbow he’d dropped to start his motion.

Max Scherzer was already walking away, his head up in disgust. Jose Tabata turned away from the pitch by instinct, and found himself facing the umpire, Mike Muchlinski, already out of his crouch, his arms extended to signal the dead ball. There was a single beat, and Scherzer forced himself to look back: Would he somehow make the call, the call that is never made? But then the moment passed, and Muchlinski pointed to first. The perfect game was over.

There was much gnashing of teeth over the result. Rule 6.08(b), often cited and rarely employed, states that not only must a batter be struck by the ball to earn his base, he must attempt to avoid it (or have it be unavoidable). Millions of fans watched the replay millions of times. Did Tabata stick his elbow out into the pitch? If he did, was it to be hit or to start a swing? If he was so fooled by the slider as to start swinging at it, did he deserve the free pass?

Then the counterarguments arrived: if Scherzer didn’t want to give up a hit by pitch in that situation (he didn’t), he shouldn’t have let it get anywhere near that elbow. How perfect could a game be, salvaged by a sympathetic umpire on a usual non-call?

Scherzer’s pitch was a bad one. It was also unlucky. PITCHf/x put the pitch at 10 inches off the inside corner, 2.7 feet off the ground. Ten inches inside sounds bad, but of the 1,395 pitches thrown within a quarter of an inch of that x-value, only 27 hit a batter. Most of those 27 were upstairs, in actual elbow range; restrict the range even further to pitches below three feet, and the resulting 1,107 pitches plunk a mere eight batters. Scherzer’s big mistake was a one-in-a-hundred outcome. Tabata, to his credit, gets hit more often than the average batter, but he’s by no means a Biggio or a Baylor.

Still, Tabata’s elbow outlines a problem that won’t go away: that rule 6.08(b) is unenforced or, more likely, unenforceable. Umpires are positioned in the best possible way to call the strike zone, and they do an admirable job. But calculating the amount of danger created by an errant pitch, and then taking the extra step of evaluating the batter’s reaction to his relative danger, all from an angle behind the body being struck: It’s a lot to ask in the span of 0.458 seconds.

The issue goes even deeper than mere logistics, however. Being hit by a pitch, when it is a choice, is a murky one to ask batters to make. Rule 6.08(b) is designed to punish pitchers who endanger batters, a reasonable enough goal. But the zero-sum nature of baseball combat means that it’s also rewarding hitters for something that just about everyone would rather avoid having happen. Even if it is one of the few times a player can sacrifice, in the purest sense of the word, his own happiness for his team, that free base is only a lure to distract him from what should be his dominant strategy: stay safe.

Fortunately, there is a way to punish the pitcher for his recklessness or meanness, while keeping the batter safe from his moral dilemma. It even rids us of the hulking, plate-crowding sluggers, covered from elbow to shin in plastic plate mail, happy to use the threat of a grazed elbow to take either a free base or take away half the plate. The solution: Take the hitter out of the equation entirely.

Recently on Effectively Wild, Sam Miller raised the topic of Bill James raising the topic of Frank Robinson raising the topic of beanballs, who proposed a similar idea. If a pitcher goes too far inside twice, regardless of whether he succeeds in his assassination or not, the umpire should throw him out. No warnings, no vagueness, just simple arithmetic. Frank Robinson had obvious incentive for wanting this rule enacted, but it’s inarguable that such a rule would be far easier to enforce than our current one.

Mine is simpler and, with the help of expensive, pre-existing cameras, more enforceable still: Any pitch thrown far enough inside is an instant walk, and the batter is free to get out of the way with no ulterior motives. Any pitch close enough to the plate, no matter what it makes contact with, is a simple ball. It’s a variation on the old robot umps argument, although perhaps a potential compromise.

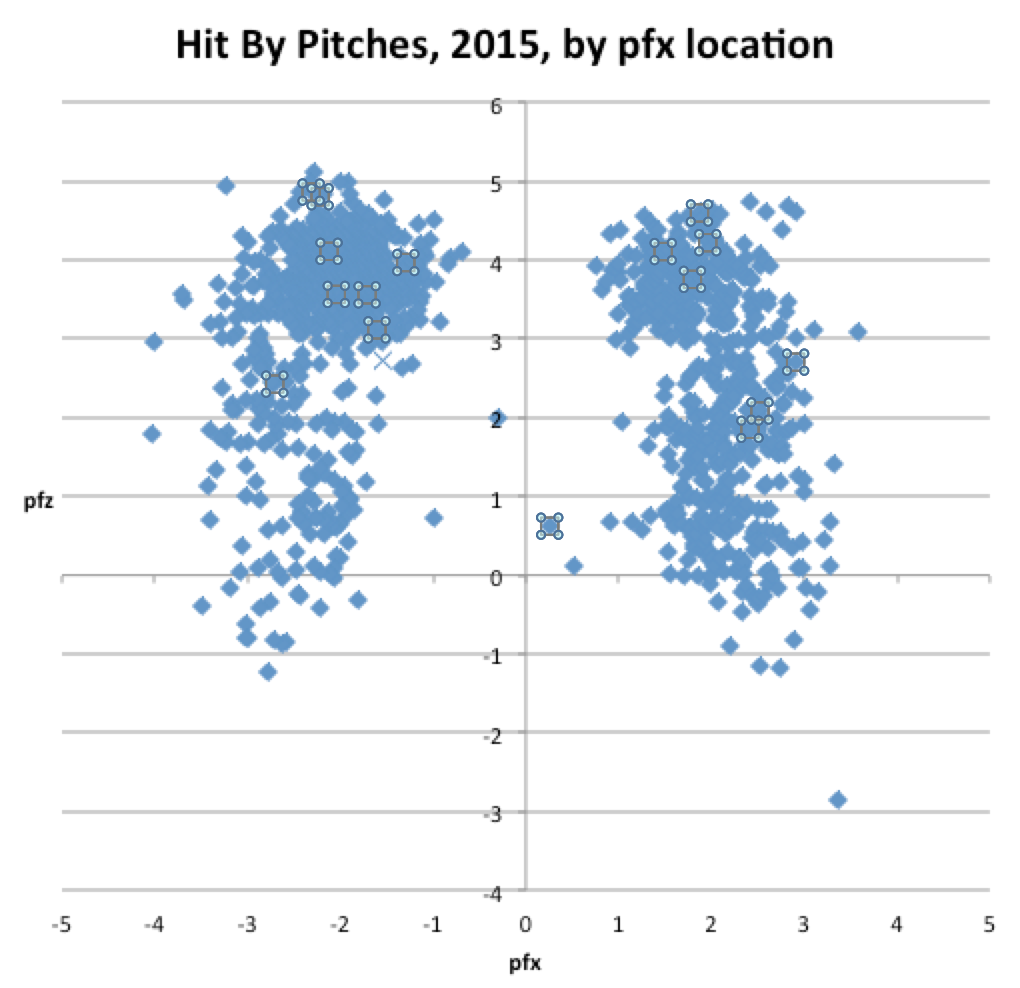

So where is the line? Where do HBPs tend to go?

(That X around (-1.4, 2.8) is our Max Scherzer example, by the way.)

The average HBP in 2015 has been 2.066 feet away from the center of the plate, or 16.3 inches off the inside corner. But this doesn’t take into account all the pitches that would have hit batters if the batters hadn’t escaped their wrath. This is a histogram of all inside pitches, in buckets of 0.1 feet, and their likelihood of hitting a batter.

|

pfx (ft) |

inches off plate |

pitches |

HBPs |

HBP chance |

|

1.5-1.6 |

9.5-10.7 |

3294 |

60 |

1.8% |

|

1.7 |

11.9 |

2419 |

73 |

3.0% |

|

1.8 |

13.1 |

1886 |

90 |

4.8% |

|

1.9 |

14.3 |

1444 |

90 |

6.2% |

|

2 |

15.5 |

1084 |

85 |

7.8% |

|

2.1 |

16.7 |

829 |

100 |

12.1% |

|

2.2 |

17.9 |

549 |

90 |

16.4% |

|

2.3 |

19.1 |

405 |

74 |

18.3% |

|

2.4 |

20.3 |

256 |

67 |

26.2% |

|

2.5 |

21.5 |

225 |

74 |

32.9% |

|

2.6 |

22.7 |

139 |

53 |

38.1% |

|

2.7 |

23.9 |

99 |

35 |

35.4% |

|

2.8 |

25.1 |

87 |

51 |

58.6% |

|

2.9 |

26.3 |

50 |

27 |

54.0% |

|

3 |

27.5 |

40 |

22 |

55.0% |

|

3.1 |

28.7 |

26 |

20 |

76.9% |

|

3.2 |

29.9 |

17 |

9 |

52.9% |

|

3.3 |

31.1 |

12 |

10 |

83.3% |

|

3.4 |

32.3 |

11 |

6 |

54.5% |

|

3.5 |

33.5 |

7 |

4 |

57.1% |

|

3.6 |

34.7 |

4 |

1 |

25.0% |

|

3.7 |

35.9 |

2 |

2 |

100.0% |

|

3.8 |

37.1 |

3 |

0 |

0.0% |

|

3.9 |

38.3 |

0 |

0 |

n/a |

|

4 |

39.5 |

2 |

0 |

0.0% |

|

4.1 |

40.7 |

3 |

2 |

66.7% |

|

4.2 |

41.9 |

0 |

0 |

n/a |

|

4.3 |

43.1 |

3 |

0 |

0.0% |

|

4.4 |

44.3 |

1 |

0 |

0.0% |

If we were to set the automatic-free-base range at greater than 2.1, based on the average hit by pitch, and remove all swinging strikes and fouls, we’d see an increase in the number of tallies from 1,211 to 1,915: a 58 percent increase. This isn’t necessarily a problem, given the lack of baserunners in the current offensive environment, though it is admittedly a drastic jump. The cutoff would have to be greater than 2.29 in order to maintain a roughly equal free-pass rate to our current standards. Of course, the almost immediate consequence of the rule would be to cause pitchers to re-evaluate the benefits of the outer third of the plate, so basing our line on current rates is a bit misleading. For purposes of practicality and public aesthetics, a rounder number, whether that is 18 inches inside or 20, would probably be preferable.

Of course, not all pitches with the same X value are equal—to statistics, or to batters. There’s a cluster right around elbow-range, beneath the three-foot mark, where hit by pitches average 2.29 feet inside, whereas above that line they average only 1.94 feet. It’s a marked difference, but attempts to adjust would only overcomplicate a potential rule, and leave people wondering why elbows are so sacred in the first place. It’s the head that we really care about, and since that danger zone moves around from batter to batter, it’s difficult to officiate. Perhaps this is where we restore autonomy to the umpire and ask him to eject anyone who throws a ball at a batter’s head, accident or no.

The updated hit-by-pitch leaderboards for a hypothetical 18-inch hit-by-pitch zone would be upsetting to some people:

|

Old Leaderboard |

HBP |

|

New Leaderboard |

HBP |

|

13 |

26 |

|||

|

11 |

18 |

|||

|

11 |

16 |

|||

|

C.J. Wilson |

10 |

16 |

||

|

10 |

16 |

|||

|

10 |

Nick Martinez |

15 |

||

|

10 |

13 |

|||

|

10 |

13 |

|||

|

9 |

12 |

|||

|

9 |

A.J. Burnett |

11 |

||

|

Chris Sale |

9 |

11 |

||

|

9 |

Charlie Morton |

11 |

||

|

9 |

11 |

|||

|

9 |

Gerrit Cole |

11 |

||

|

9 |

11 |

|||

|

9 |

Jimmy Nelson |

11 |

||

|

Chris Bassitt |

8 |

11 |

||

|

8 |

10 |

|||

|

8 |

Odrisamer Despaigne |

10 |

||

|

8 |

10 |

|||

|

8 |

10 |

|||

|

James Shields |

8 |

Chris Heston |

9 |

|

|

8 |

Jeff Samardzija |

9 |

||

|

8 |

9 |

|||

|

8 |

9 |

|||

|

8 |

9 |

|||

|

8 |

9 |

|||

|

8 |

13 tied at |

8 |

||

|

13 tied at |

7 |

Nick Martinez remains near the top of the list, where he belongs, as does Jimmy Nelson. But the rest of the list is confusing. Chris Heston actually loses a couple HBP along the way, as do a few other pitchers. But the big takeaway is that our new hypothetical rule concentrates the distribution of HBPs toward a certain subset of pitchers who intentionally prefer to work inside. The most glaring example of this is Cole Hamels, whose HBP total jumps nearly fivefold. If he’s throwing inside so much, how is he not hitting people?

The answer is in his pz scores: Hamels tends to throw inside, but also very low. More than a third of his pitches greater than 2.1 feet inside also come in less than a foot off the ground, which makes it easier for batters to leap out of the way. They’re also, unsurprisingly, in the form of off-speed stuff, giving the batters more time as well. A model that didn’t want to punish one already heaped-upon Cole Hamels may have to take pitch speed into account.

The takeaway is that any model complicated enough to maintain the current balance of hit by pitches, and current pitching behavior, is bound to be too complicated to find either reliable calculation or widespread approval. But even if Rob Manfred somehow put this idea into practice tomorrow, there will come a time, about two minutes after the next batter is seriously wounded by an ear-high fastball, when something will need to be done. Years of engaging in an endless string of petty headhunting and umpire soul searching have done little to protect against the growing number of three-digit fastballs. It may be time for baseball to take a step back in terms of romanticism, and let the unblinking cameras, and their sensible, sensible numbers, save the day.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

It appears that a curved line would have to be drawn. That leaves a computer to call HBP, individualizing the curve to the batter body. I say that because not only does height vary, but trunk length versus leg length, and arm length relative to body length vary within people. Only a computer model could do a reasonable job.

I believe in the human element of the game. These games are played by people, and for people. There are too many of us who appreciate the human aspects of the game, the human confrontation that happens on the baseball diamond. This would take the fight over "the rules" of the game out of baseball.

Catchers have a lot of value in manipulating the perception of umpires. I think that is a huge skill set that is a genuine human element to the game. It will be a much poorer game if computers take that away from the game.

This disingenuous "genuine human element" is much preferred over a correct call?

Accuracy would make for a "much poorer game?"

I respectfully disagree.

My theory in keeping the model simple, and using a single straight line, was to make the change more palatable to fans and players alike. But my colleague Brendan Gawlowski raised an excellent point offsite: creating a second zone for less deadly pitch types or velocities. Make the HBP range 18" off center for fastballs, or anything over 80 mph, and another wider zone for slow, harmless breaking stuff.

I think this extra rule works better than a diagonal zone, which becomes difficult to measure by the naked eye and results in a greater sense of unfairness.

ie - what's the point in crowding the plate if all it does is increase your risk of injury? Wonder where Bonds would have set up.