Baseball fans are, I believe, somewhat self-conscious about the sport. Maybe that’s true of fans of every sport, but I don’t know about other sports, and I do know that when something monumental happens in one of those other sports, baseball fans are quick to use it to illustrate why baseball is (supposedly) supreme.

Something monumental happened in basketball last week, when Kevin Durant announced he was signing with the Golden State Warriors. This is a big deal, because the Golden State Warriors were extremely good this past year, winning the most regular season games ever and coming one game short of the championship, and because Kevin Durant is also extremely good, apparently one of the top three or so players in the game. This leads to a team that, on paper, is extremely, extremely good. (I don’t know anything about basketball.)

Basketball free agency is really different from baseball free agency, since basketball teams are limited in how much they can offer any single player. A number of teams made “max offers” to Durant, and tried to differentiate themselves from the others with various creative pitches. The Celtics crossed sports, and brought Tom Brady, a football player, to their meeting with Durant. He eventually chose the team that was staffed by tons of other incredibly talented players in the Warriors, whose pitch was probably something like “we win a lot already, and will win even more with you, and winning is super fun.” Good pitch!

We don’t have that kind of thing in baseball, with no caps on the salaries an individual player can make. Soft factors might still come into play sometimes—there were reports that some of the players the Cubs signed this offseason did so to play for Joe Maddon, and to try to break the Cubs’ championship drought—but teams can always offer more money, and that’s usually what drives the decision. So when Durant signed with the Warriors, in the baseball-centric milieu I reside in, I saw a lot of praising of baseball’s more egalitarian set-up. Players get paid, and while there’s a much larger gap between baseball’s rich and poor teams than basketball’s, the prevailing wisdom is that baseball is actually more fair. Poor teams can still win, and the elite players don’t flock together to form “super-teams” that might threaten the competitive integrity of the league.

That’s not exactly wrong, but it certainly leaves a lot out. Baseball might have a reputation for fairness, but its mostly due to the isolated successes of a few low-spending teams. It’s true, poor teams can succeed: from 2001 to 2015, about 25 percent of teams with the lowest, second-lowest, or third-lowest payroll in the league won 85 games or more, and about 15 percent won 90 games or more. The 2001 Athletics won 102 games, and had a payroll just slightly more than half of league average, the 29th lowest in the league that year. The 2008 Rays won 97 games with the 28th-lowest payroll, also about half of league average. Last year’s Pirates won 98 with the 24th-lowest payroll, at 72 percent of league average. It is clearly possible for poor teams to win. But I’d argue that for a league to be “fair,” it also has to be possible for the rich teams to lose, and that hasn’t really been the case in major-league baseball.

If an owner is willing to spend enough, he or she can basically guarantee a successful team. Over that same period, 2001–2015, there have been 14 teams with payrolls more than double the league average: the Yankees, every season from 2003–2013, and the Dodgers, from 2013–2015. They averaged a cool 95 wins each season, and broke the 100-win threshold three times. These super-rich teams win 100 games at nearly the same rate the teams with the three lowest salaries win 85 games. They never won fewer than 85 games, and only won less than 89 once.

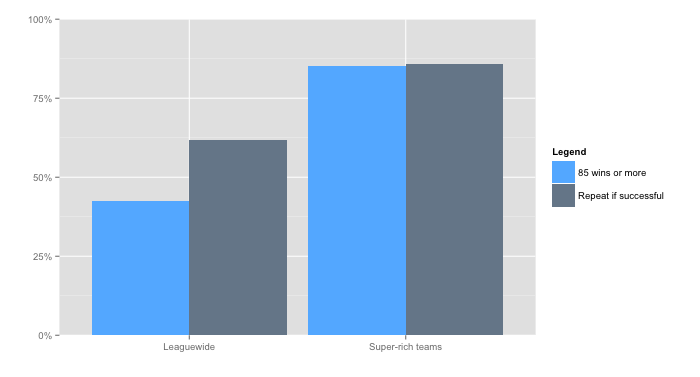

When I started this, I hoped to see some kind of evidence that poorer teams had a secret advantage, or that rich teams were hampered in some way by their piles of money. Perhaps, I thought, when poor teams do succeed, it’s more likely to be sustainable. To win a lot on the cheap usually requires good, young players paid sub-market rates, and those are often players you’d expect to improve as they age into the primes of their careers. Maybe poor, successful teams are more likely to be nascent dynasties, while rich, successful teams are just collections of free agents who might age out. Nope! Not only do super-rich teams (defined as teams with a payroll at or above 170 percent of the league average) win at least 85 games far more often than the league as a whole—85 percent to 42 percent—they follow that up with another successful season more often as well, 86 percent to 62 percent.

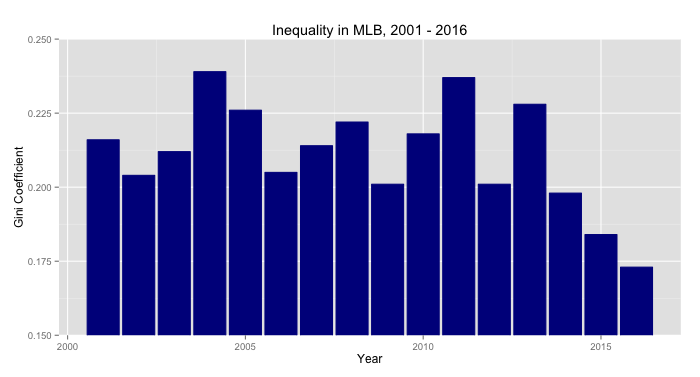

The saving grace in all this? So far, 2016 is bucking the trend. It’s true that the Yankees, the team with the second-highest payroll, are currently projected to finish the season with only 82 wins, and Cleveland, the team with the sixth-lowest, is projected to finish with 94, but that’s not what I’m talking about, exactly. This is a single year; even if all the low-income teams were winning, and all the high-income teams were losing, there would be only so much one could conclude from 2016 alone. Instead, it’s the payrolls themselves that are notable. The Dodgers have the highest payroll of 2016, but it’s “only” 182 percent of the league average, the lowest that the highest payroll has been since 2001. This is the first year since 2002 that no team has been above 200 percent. The gap between the highest and lowest payrolls, scaled to league average, is the lowest it’s ever been in this period. The Gini coefficient, a statistic that measures inequality and takes into account every data point, not just the highest and lowest, also reached a new low in 2016. The previous lowest Gini came in 2015, and before that, in 2014. It sure looks like a trend.

The real problems of balance arise almost entirely with the super-spenders described above. Teams in a more moderate spending range, with payrolls between 130 percent and 170 percent of league average, don’t enjoy the same guarantees of success that those from 170 percent and up do. They win at least 85 games 58 percent of the time, higher than league average but very much in the same ballpark, and they follow up a successful year with a second successful year 69 percent of the time, also only slightly higher than the league average. Teams in this upper-middle-class group have an advantage, unsurprisingly, but to nowhere near the extent the ultra-rich teams do. If even the richest teams could be kept close to or within that second tier of spending, I believe the league would experience much more turnover, and every organization would have a substantial chance of failing. Major-league baseball would be more fair. Thus, if this apparent trend of shrinking inequality is real, it’s a good thing.

I’m hesitant to label it a trend, however, when I can’t think of a good explanation for why teams are exercising more restraint than they have in the past. The one possibility I could imagine: The luxury tax is structured such that repeat over-spenders get punished particularly severely. The penalty rises from 17.5 percent in the first year a team is over the threshold to 30 percent in the second consecutive year, then to 40 percent, then finally to 50 percent in the fourth consecutive year and each subsequent year over the threshold. As a result, every team has a huge incentive to get under the cap once every few years, and reset their penalty clock by doing so. Maybe this flattening of the financial playing field is the luxury tax doing what it’s supposed to, and pulling the super-rich closer to the cap. But this system has been in place for a while, so while the Dodgers and Yankees appear to be taking heed of it right now, there’s no reason they can’t return to their free-spending ways in the future, and no reason some other team can’t decide to challenge them for the top payroll spot.

I don’t have any solutions to offer. I don’t like basketball’s system, and I think the kind of free agent courtships that it and other sports with caps have to go through (and the super-teams that seem to inevitably result) are not cool. Baseball’s system lets players get paid, which is great, but it should also strive to keep the league competitive and fair. Baseball is more financially balanced this season than it has been in a long time, but I’m not sure if that’s because of the league’s rules, or just a coincidence. I’d like to find a way to maintain this balance, and I’d like to see it in the next CBA.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

It's a great time to be a fan.

MLB Owners do fine, large or small, so no tears there.

MLB Players do fine, so no tears there.

MLB Fans of Big Spenders (aka Large Markets) get to see their team win disproportionately, so they are fine.

MLB Fans of Small Spenders (aka Small Markets) are not fine. Yes, there are exceptions, but lion's share of the perennially non-factors are small market teams.

I have been an active Padres fan for 35 years and have gotten to witness 5 playoff seasons and 3 playoff series wins during that time. Some of this was self-inflicted but feel San Diego actually has had pretty good management (AJ Preller gets an F for 2015 but an A for 2016 so too early to tell).

How change it? Salary band (high, low), defined as a % of baseball revenue (to be negotiated), coupled with revenue sharing from large markets to smaller markets.

But will not happen any time soon because the only people unhappy are small market fans who have been paying attention long enough to become cynical. There are fewer of them than large market, and the deterioration of fan support will be slow, steady, hard to see year to year but hard to reverse.

It's not a great time to be fans of those teams.

I wonder if the recent trend in payroll parity is driven by a leveling of player development and value assessment acumen. If all 30 teams value players similarly, there's no reason to overpay for players, whether those players are top, middle or bottom tier. In other words, improved performance analytics has created payroll leverage on the part of the clubs. MLB has, perhaps, finally, attained third-stage hell.

With the exception of the Rays and the A's, you see most of the MLB teams capable of running a $120m payroll if they're trying to win. And even those the Rays and A's aren't in the $15mil range like they were in the recent past. Which has 2 effects - math (it's hard to spend 200% of 140mil) and talent (even the Pirates, Rays, Twins and Brewers can afford to lock up their players if they want to.)

Last year was a bit of an exception with Heyward, Price and Grienke, but owners and GMs have gotten a little smarter and no longer want to pay $200m for a 32-year old free agent who somehow didn't get locked up before free agency.

Look at the Dodgers - to get to the $270m or whatever they're running these days, they had to pay $50m worth of players to sit on the DL.