The wonderful thing about subjectivity is that it lends itself to discussion. We all love to debate anything that can’t be definitively proven (some don’t even need that end clause), and although we’re moving towards being more precise in measuring everything on the diamond, there’s still so much left for the water cooler or the bar. It was at the latter that two conversations I’ve had a few times before sprung up again:

1) “Why didn’t they just fly the eagles to Mordor[1]?”

1) “What was the most exciting playoff game you’ve ever watched?”

2) “What was the most exciting playoff series of all time?”

These are overly innocuous questions that almost assuredly says more about the person answering the question than the game itself. The answers are driven most often by the individual’s formative baseball years, and over time those classic moments from your past evolve more into bloated caricatures with every passing day, as they sit adjacent to your current failures. Whether it’s a high- or low-scoring game speaks to one’s inherent values as a baseball fan and their platonic game ideal. Whether the hometown team won or lost is really, at its heart, a personality test. Cutting through the secondary factors that color these answers is impossible in that setting, but here we can do just that[2].

We’ve been told many things about our post-season baseball experience ever since the first time we tuned in. We’ve been told it was written in the stars. We’ve been told that it’s magic. We’ve been told it’s when heroes are born. We’ve been told that there’s only one October. Yet, in fact, there have been 111 Octobers—and they have not all been created equal. There’s very little fawning[3] over the 1989 post-season, which saw only 14 games total and a World Series that featured four contests over two weeks, none of which were closer than three runs. On the other hand, the shock and awe of the 2003 post-season was undeniable, featuring two of the most enduring Championship Series in recent memory. The story lines helped, but the baseball was intense.

So as we are about to roll into October #112, I set out to answer these questions as definitively as possible using a combination of available data and crowdsourcing. I then compared the results against a survey of the same questions to see what biases we have when answering these questions back in the bar[4].

Starting Point and Shortcomings

First we start with the best baseline to use for measuring the excitement of a single baseball game, regardless of the month in which it’s played. Something that encompasses the three pillars of what makes games more memorable: closeness of score, lead changes, and extra baseball. Fortunately these are all captured by swings in Win Probability Added (WPA), so the starting point is going to be absolute sum of all changes in WPA. Let’s call this Win Probability delta (WPd).

The unseasoned version of this metric quickly begins to show as problematic when you start sorting playoff games by its column. The largest bias of these initial rankings is that, since WPd is purely additive, it skews towards more towards the quantity than the quality of baseball, and that just ain’t right. It rewards the compilers, the Rafael Palmeiros of postseason games. According to straight WPd, the 13th most exciting playoff game of all time was the 18-inning marathon between the Giants and Nationals in the 2014 NLDS. Was this game memorable? Sure. But it’s certainly not remembered for its excitement value. There were no hits in the 15th, 16th or 17th innings. Gary Brown got into the game for goodness sake[5]. Same applies for Game Four of the 2005 NLDS between Astros and Braves, which ranked seventh in WPd. The only hit between the top of the 12th inning and the top of the 17th inning was a sacrifice-bunt-turned-single by then 47-year-old Julio Franco[6].

In fact, out of the top 50 games by WPd, only one lasted the standard nine innings—and I feel pretty confident in saying that it’s not a game you could guess easily[7] (or possibly at all).

Two secondary factors then come into play, and introduce a necessary human element. After all, any number implying that an ALDS game is just as exciting as the same game played in the World Series is just flat-out wrong. Among the top 30 postseason games by WPd, only seven were played on October’s largest stage, including just one elimination game. I’ll go out out on a limb and assume you can guess which game that is.

(Sorry, Rangers fans.)

(Sorry again, Rangers fans. Promise that was the last one.)

Speaking of elimination games, most of those same top 30 games range from games one through for of a given series. There were only seven contests overall that took place in either Game Five or Game Six, and nary a Game Seven to be found. Even the CliffsNotes on baseball states that a Game Six is more exciting than a Game Two.

The Crowdsourcing Effect

As a solution to the questions I wasn’t able to just answer by looking at more numbers, I created a survey to get to the heart of just how much we should account for these contextual factors. Here are the ten questions I sent out into the universe:

1) How much more likely are you to watch Game Five of a playoff series than Game One?

2) How much more likely are you to watch Game Six of a playoff series than Game Five?

3) How much more likely are you to watch Game Seven of a playoff series than Game Six?

4) How much more likely are you to watch an elimination game in the Championship Series than the Division Series?

5) How much more likely are you to watch an elimination game in the World Series than the Championship Series?

6) I am ___ percent more excited to watch a game once it goes into extra innings.

7) A game in the 12th inning is ___ percent more exciting than a game in the 10th inning.

8) A game in the 14th inning is ___ percent more exciting than a game in the 12th inning.

9) Do you consider the Wild Card game to be a playoff game?

10) What is your ideal final score for an exciting playoff game?

The point of the first half of the survey was the generate game- and series-dependent factors for weighing context appropriately. Here’s what I came up with:

Five-Game Series Game Factors:

|

Game |

Factor |

|

1 |

1.000 |

|

2 |

1.050 |

|

3 |

1.153 |

|

4 |

1.303 |

|

5 |

1.647 |

Seven-Game Series Game Factors:

|

Game |

Factor |

|

1 |

1.000 |

|

2 |

1.020 |

|

3 |

1.050 |

|

4 |

1.090 |

|

5 |

1.153 |

|

6 |

1.303 |

|

7 |

1.647 |

Series Factors:

|

Wild Card Game |

0.759 |

|

Division Series |

1.000 |

|

Championship Series |

1.220 |

|

World Series |

1.549 |

The calculations were then done by averaging the variables involved and multiplying the WPd by the smoothed circumstantial factor. For example, a 5.0 WPd contest in Game Five of the ALCS would be measured as 5.0 * [(1.153+1.220)/2], to get an AWPd (Adjusted WPd) of 5.92325.

However, this really doesn’t address the primary shortcoming of raw WPd mentioned above. The compilers are still overrepresented, and we can use that group of extra-inning-related questions to see just how additive these numbers should be. Starting at the first question (number six above), extra-inning games are approximately 27 percent more exciting than standard nine-inning affairs. It should be noted that this doesn’t seek to quantify how much more exciting a 10th-inning at-bat is than one in the seventh, but instead how much value being accruing in these games should stick.

Over the course of post-season history, the average WPA per play, broken out by inning, is as follows:

| Inning | Avg WPA/play |

|

1 |

0.03248 |

|

2 |

0.03218 |

|

3 |

0.03180 |

|

4 |

0.03321 |

|

5 |

0.03201 |

|

6 |

0.03385 |

|

7 |

0.03158 |

|

8 |

0.03304 |

|

9 |

0.09097 |

|

10 |

0.09538 |

|

11 |

0.10378 |

|

12 |

0.10621 |

|

13 |

0.07448 |

|

14 |

0.10133 |

|

15 |

0.09244 |

|

16 |

0.10057 |

|

17 |

0.06691 |

|

18 |

0.12259 |

The question raised at this point is whether a measurement of WPd per inning is a more accurate representation of a game’s true excitement than just the additive version. First, what we know: there have been 152 extra-inning games in postseason history, and both the mean and median length of these games is 11 innings. Now, we can use average WPA per play to see just what the difference is between nine- and 11-inning games:

Average WPA per play for nine-inning games: 0.0390

Average WPA per play for 11-inning games: 0.0500

Amplified excitement: 28.2%

Well, look at what we’ve got here.

Turns out that WPd per inning (WPdPI) is a near perfect match based on our crowdsourcing results on question number one. The remaining questions don’t quite approach the same accuracy, but by WPdPI, a 14-inning game is approximately 33 percent more exciting than a 10-inning contest, and by our crowdsourcing method, it’s around 23 percent. This makes WPdPI slightly overstate games in the 12-15 inning range (by the time you get past 15 innings, you’re back to within the margin of error), but this is such a small impact (and small sample—it’s 43 games out of nearly 1400 total) that we’re going to bypass it.

And with that, we finally have our game metric.

Adjusted WPdPI and Its Findings

Nearly two thousand words into the article and we’re finally going to talk about results. I never promised swiftness, really. And the results make more sense with the amplified context. Rather than one game in the top 50 that lasted only nine innings, we have 18, and we’re littered with Game Five, Game Six and Game Seven monikers, as common sense (and crowdsourcing) would dictate. Let’s see what the top 10 games in postseason history are when ranked by Adjusted WPdPI.

10) Mariners 6, Yankees 5 (F/11), ALDS Game Five (October 8, 1995)

For most of us, this game is a staple of this conversation. It also has the added WPd benefit of the extra-inning comeback. From David Cone’s 147th pitch walking home Alex Rodriguez in the eighth to both Jack McDowell and Randy Johnson (each Game 3 starters and recent Cy Young Award winners) taking over in the ninth and taking the game to its ultimate and unforgettable conclusion. The kid, overjoyed.

9) Blue Jays 15, Phillies 14 (F), World Series Game Four (October 20, 1993)

This is not the Joe Carter home run game, but it did feature a Mitch Williams blown save and loss just the same. It’s also the highest scoring game on this list—and it’s not particularly close. The Phillies had a three-run lead after the second inning, a five-run lead after the fifth and another five-run lead after the seventh. At that point, the Blue Jays’ chances of pulling this one out stood at a paltry two percent. Two pitchers, five hits, and two walks later, those chances roared up to 70 percent. Mike Timlin and Duane Ward then closed down the 15-14 victory by retiring six straight batters.

8) Mets 6, Red Sox 5 (F/10), World Series Game Six (October 25, 1986)

This game needs no explanation, as it has one of the most indelible moments in the sport’s history, but it’s worth mentioning two quick things. First, as we celebrate the retirement of the most clutch Red Sox player, I wonder how Dave Henderson (who homered in the top of the 10th to give the Sox the lead) would have been remembered if his 1.097 OPS and two enormous home runs, including this one from the week prior, had propelled them to a championship. Second, of all the games mentioned here, this was the only one where the prevailing team’s win probability touched one percent. This happened after Wally Backman and Keith Hernandez both flied out to start the famed bottom of the tenth inning (yes, it all started with two outs).

7) Yankees 5, Giants 4 (F/10), World Series Game Five (October 5, 1936)

I’ll be honest, this one seemed at first like a little bit of a head-scratcher. Sure it’s helped along by the fact that it’s Game Five of the World Series, but it was also a very tense game throughout—with the teams remaining within a run of one another from the third inning on. Hal Schumacher pitched a valiant 10 innings, allowing 16 base runners and getting out of a few high-profile jams. The largest of these was in the third inning, when he had a one-run lead and loaded the bases with no outs for Joe DiMaggio and Lou Gehrig. He struck them both out. To put this in perspective, DiMaggio and Gehrig struck out a combined 85 times during the entire regular season. Also, this game ended on a caught stealing—though it received no extra points for so doing.

6) White Sox 7, Astros 5 (F/14), World Series Game Three (October 25, 2005)

This series, and we’ll get to this in a future article, doesn’t get remembered as one of the great ones of our lifetime. It was a sweep and featured two teams without mass national appeal. However, all four games were barnburners from start to finish—especially Game Three. The Astros’ offense staked Roy Oswalt to a 4-0 lead through four innings, but the ace coughed it up in a five-run fifth. The game stayed that way until Jason Lane[8] pulled a double down the line to tie it in the eighth. The Astros got at least two men on base in the ninth, 10th and 11th innings to no avail. Finally, with two out and no one on, the White Sox rallied for two in the top of the 14th. After a few baserunners for good measure in the bottom of the frame, they brought in Game Two starter Mark Buehrle for the improbable save[9]. It was the only save of Buehrle’s career.

5) Red Sox 6, Giants 6 (F/11), World Series Game Two (October 9, 1912)

This should be one of the most famous World Series ever played, but since it happened more than a century ago, it settled in as a rarely-remembered antiquity. If we’ve been looking for quirky things about each and every one of these top 10 games, this one is the easiest to find. The game ended in a 6-6 tie due to darkness[10]. It wasn’t picked up from that point the following day either; it was lost entirely in the context of the series with the Red Sox entering Game Three with a 1-0 lead in the series. Christy Mathewson twice lost the lead on unearned runs (in the eighth and tenth), but neither was the most disappointing moment of the series for him. We’ll get to that later.

4) Yankees 3, Cardinals 2 (F/10), World Series Game Five (October 7, 1926)

With the series knotted at two, Herb Pennock and Bill Sherdel dueled for 10 innings at Sportsman’s Park in St Louis. The Cardinals took two one-run leads but vanquished the second one in the ninth inning as Lou Gehrig scored on a Ben Paschal pinch-hit sacrifice fly. Another sacrifice fly, after walks to Gehrig and Babe Ruth, gave the Yankees a 3-2 lead in the 10th inning that they wouldn’t relinquish. Unfortunately though, the victory wasn’t enough as the Cardinals won the next two games (albeit in slightly less dramatic fashion) to take their first World Series title.

3) Phillies 8, Astros 7 (F/10), NLCS Game Five (October 12, 1980)

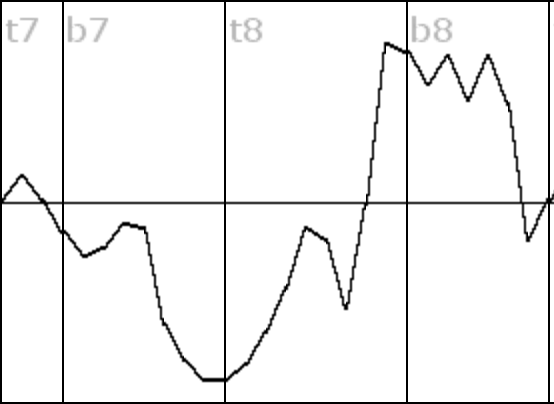

Back in the early eighties, League Championship series were only best-of-fives, and this one packed all of the punch of any seven-gamer. Game One was the only contest decided in nine frames, as the series ended with four straight extra-inning affairs. Game Five was just your ordinary close elimination game, sitting at 2-2 after six innings. Then this happened:

(courtesy of Baseball Reference’s Win Probability graph)

I’m dizzy just looking at it. A three-run lead for the Astros became a two-run deficit and then all square again as quick as a Nolan Ryan fastball[11]. The Phillies took the game in extras and rode the momentum to a World Series victory over the Royals.

2) Red Sox 3, Giants 2 (F/10), World Series Game Eight (October 16, 1912)

And we’re back to 1912. The fact that Game Two ended up a tie led to one of only four Game Eights in baseball history—though this is the only one to take place in a best-of-seven series. After the six unearned runs he gave up in Game Two, Mathewson was again let down by his defense in the series’ prestige. He was staked to a one-run lead in the top of the 10th inning on a Fred Merkle single, but a lead-off pop up dropped by centerfielder Fred Snodgrass[12] opened the door for the Red Sox to score two in the bottom of the inning and take the series in walk-off fashion. Snodgrass’ error would go on to be known as the “$30,000 Muff”.

1) I know I promised, Rangers fans. Really, I’m truly sorry.

Later in this series we’ll get into how to measure playoff series, trends of Adjusted WPdPI, why your favorite series/game may not rate as highly as you’d think, some of the worst games in playoff history, and the qualitative things WPdPI simply cannot take into account.

Thanks to Rob McQuown for research assistance[13]

[1] Hi, Ben.

[2] Unless you’re reading this article in a bar, in which case bless your heart.

[3] Sorry, Patrick.

[4] Read: gchat, Twitter, etc.

[5] He struck out, naturally.

[6] Next phase: factor in at bats from 45-plus Julio Franco.

[7] This would be the first playoff game ever played in Coors Field—Game One of the 1995 NLDS between the Braves and Rockies.

[8] Yes the one who showed up as a pitcher in San Diego last year.

[9] In over 3,300 innings between the regular season and playoffs, Buehrle had just one save. This was that save.

[10] This is even more incredible because simply the act of a team winning a game is the biggest spike in WPdPI you can expect. For this game to be on the list without that, well, it’s incredible.

[11] The four straight baserunners he allowed in the top of the eighth all came around to score, so maybe this should read “quick as the exit velocity on a Nolan Ryan fastball”.

[12] This is just a reminder that there used to be a lot more people named Fred.

[13] Remember what Sam said in his farewell article, this statement means this article was *Chris Traeger voice* literally not possible without Rob.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Better question, why can't Star Wars Empire soldiers and pilots hit a damn thing with their guns? They are worse shots than Indians in some cookie-cutter Western ca. 1955.

1. The Fisk game (G6, 1975 WS)

2. The Bobby Thomson game. This wasn't technically a playoff game, but I would count it similar to the Wild Card game.

3. G7, 2001 WS.

When Frodo and Sam get to Mt Doom, there is nobody home. That is because Sauron has been suckered into thinking that Aragorn has the Ring and the big fight for top dog in Middle Earth is going to be at the Gates of Mordor. Sauron has called everyone to the Gates. Yes, it is spine-tingling when Sam and Frodo get dragooned into an Orc column heading for the Gates, but once they head out east to Mt Doom, there is no one but Gollum.