Note: This article was originally published on October 23, 2017. We’ve decided to re-run it after Twins general manager Thad Levine revealed yesterday that Glen Perkins is retiring.

Last week, the Twins announced that they would not be picking up their $6.5 million option on left-hander Glen Perkins for 2018, making him a free agent after 14 years in the organization. It was an expected move, and in fact Perkins and his teammates got very emotional during his final appearance of this season precisely because everyone seemed to recognize the writing on the wall.

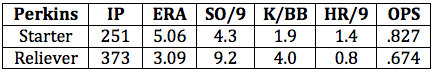

Perkins hasn’t been healthy since late 2015, which was his third of three straight All-Star seasons and his fifth consecutive season as an elite-level reliever. He struggled down the stretch that year and logged a grand total of just 7 2/3 innings in the two seasons since, spending much of that time rehabbing from a torn shoulder labrum.

I’m biased when it comes to Glen Perkins.

For one thing, we’re both Minnesotans, although there’s more to it than that. He starred for the University of Minnesota baseball team in the early 2000s while I was on the same campus, uh, not starring for the journalism school. He’s been one of the most fan-friendly Twins players of all time, particularly on Twitter and via his involvement with local charities. We once shared a Heggies pizza around midnight, which is a time-tested bonding experience. Four years ago, during a late-season Twins game, I was hosting a Target Field pub crawl with a few dozen of my closest friends and, after a lengthy rain delay, Perkins sent his personal credit card up from the bullpen to a bar to buy us all a round of drinks. And most recently, Perkins wrote the foreword to the Baseball Prospectus Annual.

I think Perkins is a helluva guy. More importantly, within the context of the things usually covered on these pages, I think Perkins was a helluva baseball player.

For whatever reason, many people get very angry at injured athletes. Being hurt becomes the player’s fault, physically or mentally, and injuries get turned into personal flaws to be criticized. And so I worry—both as someone who thinks quite highly of Perkins as a person and as someone who simply wants baseball players to be properly credited for their on-field performance—that Perkins’ excellent run as a top-flight setup man and All-Star closer will become lost in the unfortunate way his Twins career came to an end.

It would be sad if his saves and strikeouts were overshadowed by his disabled list stints and rehab setbacks, and if his giving the Twins a “hometown discount” on a 2014 contract extension at the height of his value later became a constant source of money-based criticism anyway, because Perkins is one of the best relief pitchers in Twins history.

Picked by the Twins in the first round of the 2004 draft, Perkins moved quickly through the minors as a polished, strike-throwing starter prospect. He was called up to the majors in September of 2006 and a few months later Baseball Prospectus ranked him as a top-100 prospect. He initially worked as a reliever and found immediate success, throwing 34 innings with a 2.88 ERA, but also dealt with shoulder problems. Following the 2007 season, the Twins traded away Johan Santana and Matt Garza, and lost Carlos Silva to free agency, so six weeks into 2008 they called up Perkins again, this time to join the starting rotation.

Perkins posted a shiny 12-4 record in 26 starts, tying for the team lead in wins, but his 4.41 ERA and 4.4 strikeouts per nine innings were underwhelming. He got off to a similar start in 2009, but then got knocked around in July and August before being shut down with more shoulder problems. When the Twins activated him from the disabled list and demoted him to the minors, Perkins asked to be examined by an arm specialist and filed a grievance, rightfully claiming that an injured major leaguer can’t be demoted to the minors. That offseason the two sides came to an agreement that awarded Perkins the service time he lost, but it was clear that he was in the Twins’ doghouse.

Perkins spent most of 2010 at Triple-A and pitched poorly there before continuing to struggle in a late-season call-up to Minnesota. At that point his career was at a crossroads and at the very least he seemed unlikely to make things work with the Twins. Perkins was 27 years old, with a 4.81 career ERA, several disabled list stints, and one very public clash with team management. Right around that time, Perkins stumbled onto Baseball Prospectus and began reading about ways to evaluate pitching beyond the traditional win totals and ERAs.

He started to become a stat-head, which he described in his BP Annual essay:

I continued to research and learn what I could do to improve my performance by relying less on the defense to make plays. By 2010, I had a decent grasp on what needed to be done—it was just a matter of putting the plan in action. I modified my pitching style and, along with a move to the bullpen and the obligatory bump in velocity, my strikeout rate went way up, my walk rate went down, and I induced more ground balls. …

It wasn’t until a trip to Costa Rica with some other players when I felt like I actually had people listening to what I was saying. In one of the more baseball-ratty things of all time, I was with a few other players on a catamaran in the waters off Central America, and not snorkeling or swimming with dolphins but holding court about the meaning of FIP and WAR. In Costa Rica! On a boat!

I realized then that the lack of stats and analysis wasn’t about a closed mindset but rather a lack of understanding. The mix of people on that boat—10-year veterans and guys with only a year or two under their belts—could not believe that there were people figuring all this stuff out and that it actually applied to what we did. It was a eureka moment for me and a day in my baseball geek life that I won’t forget.

Perkins shifted to the bullpen full time in 2011 and never looked back. He appeared in 65 games, throwing 62 innings with a 2.48 ERA and 65 strikeouts while allowing just two homers. By the middle of 2012 he was the Twins’ closer, finishing that season with 16 saves to go with a 2.56 ERA and 78/16 K/BB ratio in 70 innings. Perkins was at the absolute peak of his powers in 2013, saving 36 games with a 2.30 ERA and 77/15 K/BB ratio in 63 innings while holding opponents to a .196 batting average. He threw harder than ever, struck out 11.1 batters per nine innings while pounding the strike zone, and made the first of three straight All-Star teams, closing out an American League victory in all three.

Saving a win for the American League in front of the home crowd in the 2014 All-Star game at Target Field is a helluva career highlight, and something Perkins probably couldn’t even have imagined in a dream back in 2009 or 2010. At the most basic level, shifting to the bullpen allowed Perkins to add velocity and focus on his fastball and slider, which in turn allowed him to more than double his strikeout rate and go from replacement-level starter to All-Star reliever.

Unfortunately, the role change did not allow him to out-run those early shoulder problems, at least not forever, and now at age 35 he’s facing a tough decision about whether he wants to continue pitching with diminished raw stuff and a new team. If he keeps going, I’ll keep rooting for him. And if he calls it quits, I’ll start rooting for him to find his way into the broadcast booth.

Perkins has the seventh-most relief appearances in Twins history, ranking third in saves (behind Joe Nathan and Rick Aguilera) and seventh in Win Probability Added. Among all relievers with at least 200 innings in a Twins uniform, Perkins is third in strikeout rate, third in K/BB ratio, and eighth in ERA. And he did all of that after nearly washing out of the majors in his mid-20s, and while talking often and openly about the role sabermetrics, intellectual curiosity, and an open mind played in his career turnaround.

Glen Perkins, Proven Closer™.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now