In the top of the fifth inning of the first game of the 2017 World Series, Clayton Kershaw threw a fastball for strike three. That’s not particularly unusual—Kershaw had 11 strikeouts over seven innings last night, racking up two called strike threes and one foul bunt off a four-seam fastball. What made this pitch unique was the way that Kershaw threw it.

Back in September, Jeff Long and I published on how the theory of pitch tunnels was evident in the body of pitching work compiled by one Dallas Keuchel, who also made an appearance in last night’s game. Mentioned in that piece was that a certain Clayton Kershaw defied the logic of tunnels, proving that they were simply one way to approach pitching, not the only way. Both Kershaw and Keuchel were excellent in Game 1—though Keuchel gave up more runs, and struck out fewer batters—and they did their jobs in the ways uniquely suited to them.

That’s not the subject of this piece, though—that can be explored at length later. Right now, we’re talking about pitch no. 57 of Kershaw’s night. In his previous at-bat, the first time he’d seen Kershaw all year, Josh Reddick singled off a 1-1 curveball. It was the first hit for the Astros, who were already down a run thanks to a first-pitch Chris Taylor leadoff home run.

Who knows exactly what Kershaw was thinking when watching Reddick walk up to the plate for the second time. Possibly nothing except the kind of blind determination to strike hitters out, maybe “this guy ruined my attempt at a postseason perfect game,” or potentially just “it’s too hot, we really should do something about this global warming thing.” Whatever it was, we’ll likely never be privileged to know. What we can tell is that Kershaw pitched as if Reddick had personally offended him.

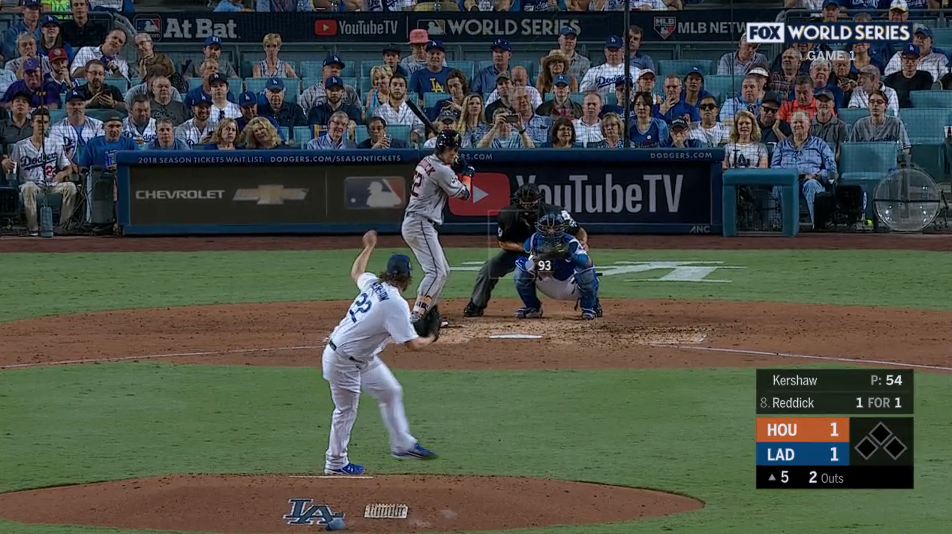

Strike one: A four-seam fastball over the outside bottom corner.

Kershaw threw a first-pitch fastball to a left-handed hitter 77 percent of the time during the regular season, so the Astros’ hitters jumping all over themselves guessing at the first pitch of any at-bat weren’t wrong to do that. Reddick takes this pitch almost casually, though, perhaps thinking of the fact that the previous two batters grounded out on a second and a first pitch, respectively. There’s a slight flinch when the ball approaches the zone, but for the most part, Reddick takes this opportunity to stare down Kershaw.

In 2017, approximately 40 percent of Kershaw’s first-pitch fastballs were strikes.

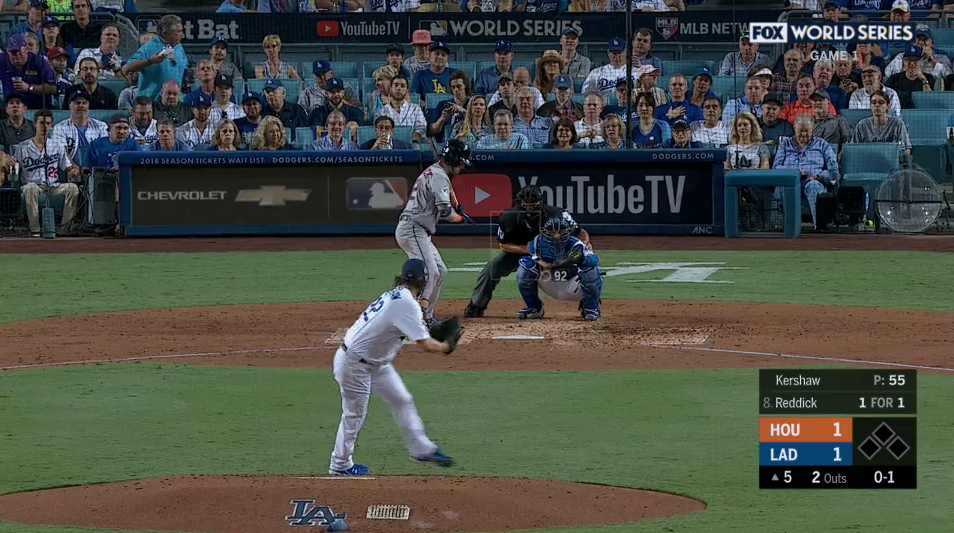

Strike two: Another four-seam fastball, again over the outside bottom corner.

This time, Reddick’s not so sure. He watches the pitch into the glove, and if you believe FOX’s somewhat suspect rendering of the strike zone, this could have easily been called a ball. It doesn’t matter, though. This pitch is just filler, just the means of getting Reddick down 0-2 against Kershaw, a pretty terrible place to be. If he can dial up the player card in his head, he’ll be expecting a slider. Even if he can’t, he’ll be expecting a slider. By this point in the game, Kershaw’s already struck out four Astros on sliders.

Strike three: Two-seam fastball, just off the center of the strike zone, right at the knees, for a called strike three.

A month or so into the 2017 season (after briefly experimenting with this in 2016), Kershaw—already one of the best pitchers of this or any era—decided to change things up. Instead of sticking to his fairly consistent release point, and already deceptive and unique delivery, he decided he could make life even harder for hitters, and change that release point. On two-seam fastballs, or sinkers, he began dropping his arm down closer to a side-arm position, something more usually seen on funky-cool relievers and teammate Rich Hill. He used this trick a few times throughout the mid-part of the year, then seemingly shelved it around when he suffered a lower-back strain that landed him on the disabled list.

Now, the outcomes on this pitch aren’t exactly the greatest. It gets put into play more than any of his other pitches, at around 22 percent of the time, and he’s almost as likely to miss the zone with it as his changeup, a pitch which it could be argued exists to miss the zone. Functionally, though, this drop-down slider works as a sort of secondary changeup, thrown mostly to left-handed hitters.

Reddick wasn’t sure what to do with it, the only drop-down pitch Kershaw threw all night. He’s frozen in a web of his own indecision. He has a brief thought to swing at it, late enough that if this were one of Alex Claudio’s 65 mph changeups (which he’s used to seeing from this release point) he might have had a chance—but this is a 94 mph missile, and the ball is already in Austin Barnes’ mitt. A second later, home plate umpire Phil Cuzzi rings him up, and all Reddick can do is shake his head.

It’s not like this particular sequence was a pivotal moment in the game—despite an Alex Bregman home run, it was fairly evident by this point that the Astros just weren’t going to be able to claw anything else off Kershaw. Even if Reddick had singled again, it was unlikely that he would have come around to score. In the grand scheme of things, this is just another out.

Taking an even larger step back from the game, though, this is proof that being the best pitcher currently in the game isn’t enough for Kershaw. That unceasing drive to improve, to make it even more difficult on hitters, is really what sets him apart. Most pitchers change their arm slots as a ploy of desperation, some hope that by throwing from a weird and awkward angle their stuff will regain the danger of their youth. Kershaw doesn’t need that—or even to warn his catcher it’s coming—he just wants to be even better.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now