Have you ever noticed how we never ask real failures their opinion on failing? Google “people who fail.” Check out the top results.

People who failed, but only at their first attempt. Highly successful people; famous people; people eventually on their way to something. Any search for quotes on failure returns wise words from Winston Churchill and Oprah and Michael Jordan and Bill Gates. Just a bunch of famous failures. It makes some kind of sense. We aren’t interested in engaging failure per se—we’re interested in lessons.

For the most part, we only ask about failure later, after the failing is over. We want to know what you learned; we want to know how you turned it around. You slept on your parents’ couch, but you got that screenplay done. The first three tries crashed and burned, but boy is that new app slick. You averted global catastrophe! It’s not that every failure gets a second act; it’s that we’re only really interested in the ones that do.

Athletes and children have it a little different. Of athletes and children we ask questions. From athletes and children we demand answers all along the way. We make them dissect their failures as they happen, though our sights stay fixed on progress, on overcoming.

Cody Bellinger isn’t a failure, but he’s been failing. Not for very long, and not in a way that is that unusual, and not even that badly when you consider how baseball can go, but failing. He’s had opportunities to help his team win, and he’s whiffed. It hasn’t mattered as much as it might, because the Dodgers have a lot of guys who can help them win, but of course it matters some. It has been at times costly.

Going into Game 4 last night, he was hitless in the World Series. His postseason was marred by 19 strikeouts, including four in Game 3.

Buddy. Those are the kind of hacks you take when doubt radiates down into your shoes.

Saturday didn’t start off much better. Bellinger flew out in the second inning and struck out swinging in the fifth inning. So far his night was marked by more failing; more questions waiting for him at his locker.

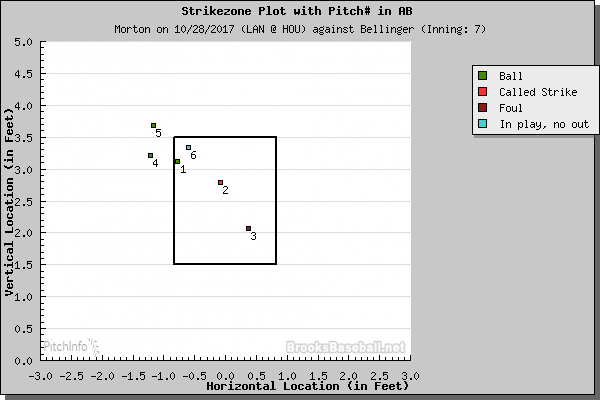

In the seventh, he stood in verus Charlie Morton again. They began. Ball, called strike, foul. Pass, fail, fail. Ball. Ball. Pass. Pass. And then? Well. “In play, no out.”

Bellinger had been failing, until suddenly he wasn’t. He sent an 80 mph curveball into left field for a double. A few feet over, and he might have been rounding the bases, but the double would do. The broadcast camera caught him swearing loudly in relief, and then a moment later you could hear “it’s a miracle.” Logan Forsythe would single him in to tie the game. It wasn’t failing.

In the ninth inning, with runners on first and second, Bellinger faced Ken Giles and sent a four-seam fastball into left for an RBI double to put the Dodgers ahead. According to Brooks Baseball, during the regular season, he saw 863 four-seamers. He hit .292 against them; he slugged .607. During the postseason, he’s seen 56. He’s hit .077; he’s slugged, well, .077. Sometimes you just have to hit like you can. Sometimes you just have to not fail.

Austin Barnes tacked on a sacrifice fly, and Joc Pederson unloaded a three-run home run to put the game away and ensure the series would go back to Los Angeles. The insurance runs provided needed cushion, but it all started with those doubles.

Bellinger will be the NL Rookie of the Year. He hit 39 home runs with a .331 TAv. He was worth 4.8 WARP. He’s a very good player. And he’s been failing. On the biggest stage, with his team down two games to one, in a small sample, with a roaring crowd, and Charlie Morton shoving, he was failing. He was sleeping on his parents’ couch.

And then suddenly, he wasn’t. Suddenly there was a miracle. What are hits if not miracles? He made contact; he broke through. He’ll fail again, because that’s what baseball players do, but on this night, he didn’t. He got different questions. He got to tell us how he did it. After the game, he told reporters: “I hit every ball in BP today to the left side of the infield. I’ve never done that before in my life. Usually I try to lift. I needed to make an adjustment, and saw some results today.”

On this night, he made an adjustment and sent a pair of doubles to left field; he got a second act. He saw results. Cody Bellinger isn’t a failure, despite the brief time he spent failing. Much to the Dodgers’ delight, he’s too busy being on his way to something else.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now