Last year, 122 players reached first base after a strikeout: more than a hundred times, a team received the opposite of a ghost runner, a living person who didn’t belong there. As far as rules go, it’s not quite at “you must never lose contact with the base for a duration imperceptible to the naked eye” bad, but it’s down there, as Sam Miller once lamented. It’s the vestigial tail of the baseball rulebook, a callback to a game when six balls were necessary for a walk, the batter could ask for the exact type of pitch he wanted, and dogs were allowed to play outfield. There’s no good reason for the rule to exist now; while it offers the opportunity for fun little records like “four strikeouts in an inning,” even admitting the possibility that someone could strike out four batters in an inning feels like a bug in the code. It’s a dumb, arbitrary rule saved only by the fact that all rules are arbitrary, that baseball is as it is because people just decided the game may as well be that way.

I would have designed the sport differently. Motion one: I would make breaking a bat an instant out. A pitch that breaks the hitter’s bat is an unqualified success on the part of the pitcher; it’s a violent, attention-grabbing thing, an exclamation, worthy of celebration. A broken bat feels like it should hold more weight in the course of a game than it does. Yet for some reason, we decided that dropped third strikes were special enough to create some loopholes, and bat snapping wasn’t. It’s random.

And honestly, as much as I feel for the people who are trying to win at a sport, I embrace that randomness. The rules and customs of a sport are what give it color, what make it into a bizarre pantomime mockery of real life, with its colorful pajamas and fireworks and artificial, hypnotic drama. In fact, the more obtuse and arcane the requirements for behavior are, the better. I understand I may be in the minority on this, but I’m rarely transfixed by sheer, unrefined feats of athleticism, the 500-foot home runs or the cartoon sliders. People are constructing skyscrapers and robots every day. We reached the goddamn moon. Nothing a man can do with a two-foot stick against a ball, particularly on the three-millionth iteration, is going to capture my imagination that fiercely.

For me, what makes baseball special is the problem-solving aspect of it, particularly when normal reasoning collides with these arbitrary, unnatural rules. It’s the abrupt, chaotic reaction of a Josh Harrison rundown, the inexplicable two-strike bunt by the DH, Aaron Judge just running for a base when he’s already both out and safe, where baseball reaches the sublime in its absurdity. The rules of baseball combine to allow for expressions of human ingenuity. The more restrictions, the more opportunities for this enjoyable stupidity that is our national pastime. And the more ceremonial the act of playing a sport becomes, the more coded its language and its analysis, the more it feels like a celebration, a harvest festival.

***

A couple of weekends ago I found myself at a friend’s Halloween house party, a 39-year-old dressed 20 years older, surrounded by twentysomethings who looked the part. We sat on thrift-store couches, swallowing light beer and watching the Dodgers lock down Game 4 when the question came. A confession: though I’ve frequented my share of watering holes, I had never played beer pong, only seeing it as a tailgate set piece, never used. I would say that, in terms of familiarity, it ranked around the same level for me as crokinole, or cricket.

The mystery was quickly dispelled. There is not a lot to beer pong: we stood in the laundry room, a folding table and 20 red solo cups between us (filled with water; we drank at our own pace). We tossed balls into the cups. I won’t romanticize it further; it’s a glorified translation of throwing playing cards into a hat, or shooting pool, or watching a baseball game. It’s a pleasant way of passing time, a test of skill in the very loosest sense. I won a few, lost a few. But what I enjoyed most about it was the rules.

Each formation of the cups has its own name: three lined up are a stoplight, five interlaced a zipper. There are house rules to be established or abolished before competition: when can you deflect the ball away, or retrieve your own on a miss? Can you blow on a ball still spinning near the lip of the cup? When do you remove extra cups? It’s an elaborate, patchwork, schoolyard system, a callback to the wallball games of my childhood, each beginning with a litany: “no corners! no drops! no headers! no…”

My takeaway was that beer pong is interesting less as an activity than as an archaeological study, an evolutionary step in the process by which games become sports.

***

I grew up in a backyard. An only child, my life was a calendar of self-appointed projects: mapping the terrain of the undeveloped marshlands behind our house, cutting paths in the stickerbushes and hunting for landmarks; creeping fearfully near the abandoned two-room shack with its decaying furniture and rusty gasoline cans and the eyeholes cut into the wall; numbering blocks of wood and hiding them over the winter to give my future self a scavenger hunt the following spring. I was a master of devising entertainments. One summer I created a miniature Olympics, marking off 25 yards by foot and then timing myself with a stopwatch as I ran, walked, and skipped across the finish line. I created a golf course by digging a single hole and planting a flower pot—one hole was all I felt I could get away with—and then hitting to it from eight different directions. I played wiffleball by myself. For most people, childhood goes too fast; I’d venture that mine extended just about the right amount.

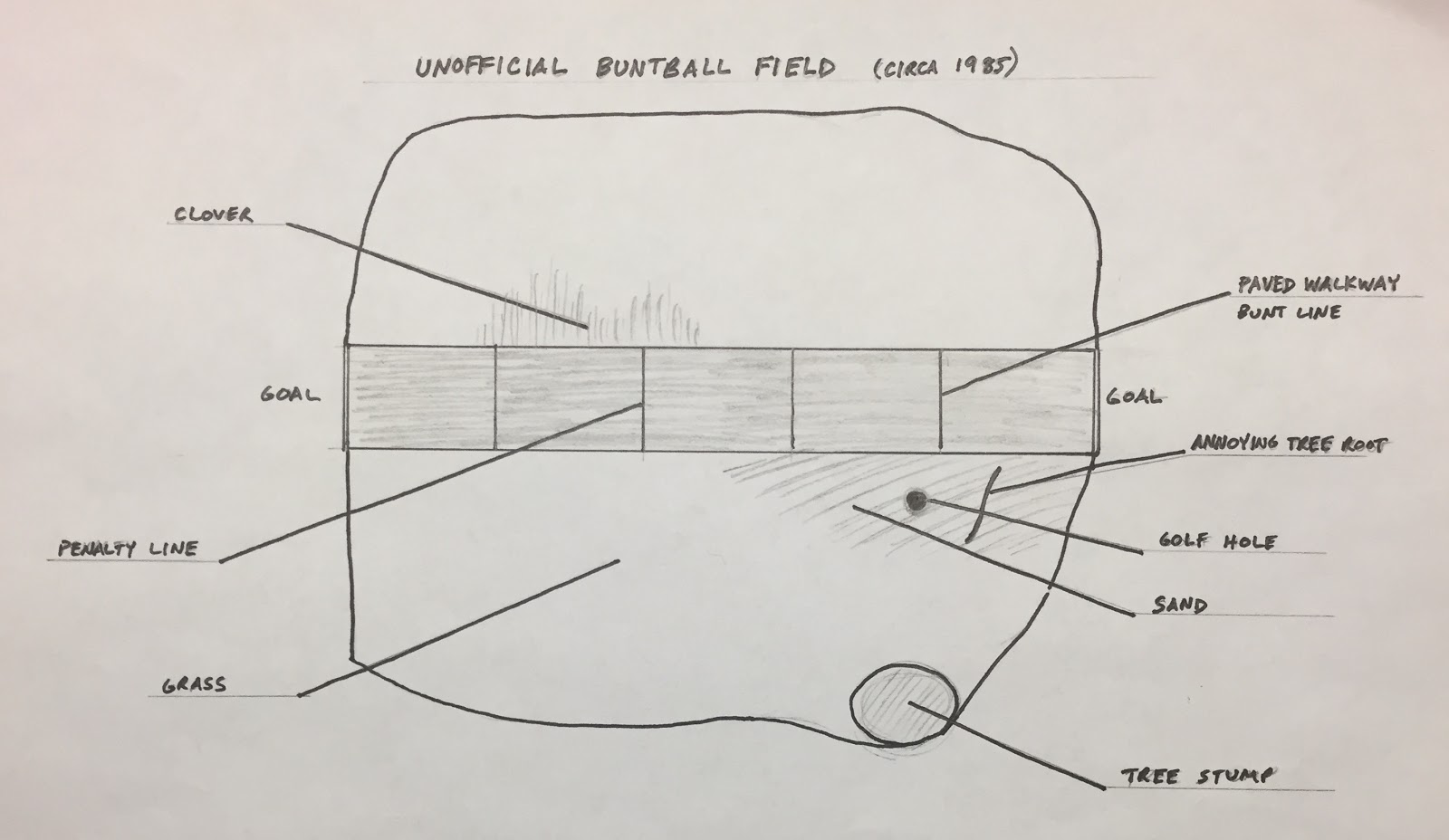

But the most Dubuque thing about my childhood was the sport I invented, entitled buntball. Buntball was a combination of baseball, golf, and soccer. I’ll lay out the rules; it won’t take long.

A point in buntball is scored when the ball (a plastic practice golf ball, typically) is struck through the goal by the bat (specifically, my faithful yellow wiffle bat). The winner was the first to 10 goals, winning by two. The ball is put into play by standing in front of one’s own goal and bunting the ball into the field of play, at which point the two players hit it back and forth on the field in an attempt to score a goal. The turn-based nature of combat was vital for allowing a single player to pretend to be both players, as one might do if one were an only child.

Goals could not be scored on bunts; doing so was a major penalty, and allowed the other team to make a bunt from the midline to score a free throw-style goal. Bunting the ball out of bounds created a similar, although more difficult, penalty. Hitting the ball out of bounds on a normal golf swing meant that the hitter had to bunt, giving the other side the next opportunity to score.

The sport gets its name from the importance of bunting; a good bunter could place the ball deep in the opponent’s territory, giving them a difficult shot and field position. The other strategic factor is the concrete path bisecting the field, because a ball hit to the center, on a shot on goal, would make for a smooth, easy corridor for the opponent if they missed. Thus the sport carried a pleasant layer of risk-reward behavior, and I imbued my fictional opponents with different personality traits and skills (some bunted aggressively, some over-hit their shots, some played conservatively). I recorded the box scores and kept basic standings.

Buntball had its flaws as a sport, of course. The 10-goal requirement was ridiculously high, and games could sometimes take the better part of an hour, especially when I was cold and both teams couldn’t hit a shot. The curved surface of the wiffle bat added unnecessarily to the difficulty of aiming, and a plastic golf club would have done the job more efficiently. Conservative play could make the game extremely boring, similar to the dump-and-chase style of hockey going on in the same era. Games were unbearable when my father had forgotten to mow the yard.

The result, from the perspective of an adult, is not the sort of sport I would want televised. But as a midsummer picnic activity, with beer in hand, it’s probably no worse than cornhole or beer pong. It’s hitting a ball around with a bat. It’s wasting time, evolved gently into something barely greater: not a sport, but enjoyably sport-like.

***

This is where the humanity of every sport is locked: within its amiable, time-wasting origins. We do something to see if we can, then find out how well we do it compared to others. It’s the kids in the backseat of the car, holding their breath while they go through the tunnel. Or golf, a quarter-mile conversion of kick the can.

It’s difficult to disentangle baseball as a multi-billion-dollar industry from the childhood games that spawned its early history. For a sport with such an incredible history, where we can track the number of hits by men who played four years after Canada became a country, what I miss most is that nascent period just before: the baseball of the 1840s and 50s, when a game transformed into a sport, and people paid and were paid for the playing of it. But even for similar, modern pursuits, the transition is incredibly difficult to see, and sometimes fails in the process. Esports are the obvious example of this, as the culture and analysis begins to crowd around the already-present money. Perhaps board games, another former childhood pursuit, will follow.

The backyard I’ve supplied my children isn’t the one given to me; it’s pleasant and suburban, wide enough to contain a game of croquet but not wiffle ball. I want to teach my children buntball, or at least make one comical attempt, but it’s not time yet; my son will still chew on a pine cone on occasion, and my daughter is far more interested in using the wiffle bat to slay bubbles and pretend that she’s Twilight Sparkle. But when the pair are occupied, I sometimes set up the wiffle ball tee-ball set and play a game.

This is a new one. It started as just hitting balls off the tee, using the pitching wedge from a plastic golf set; the materials combine perfectly, so that I rarely hit it over the fence when swinging at full power. The aim is for the perfect line drive: a column between the ropes of the swingset ahead. After I hit all four balls, I walk down and hit them back. It’s amazing how naturally rulesmaking comes back: I give myself three hits for each ball to touch the base of the tee at the top. If a ball strikes another ball, it’s a free shot. Hitting the tee itself, off the ground, provides “forgiveness” on one other ball that fails to make it back in the allowed three strokes. Like the perfect arbitrary ruleset, I almost always succeed. It’s pointless, and complicated, and it kills time while my wife cooks dinner. It’s childhood, eternal childhood.

This sport doesn’t have a name, and it probably won’t deserve one. The encroachment of autumn will draw its season to a close, as with baseball, and next year it will likely be replaced by something else. But under the gray Seattle sky, as the kids played in their kinetic sandbox on the deck, I took a couple more swings.

The final ball had that perfect resonance up the arms, the signal to the brain that something is right, and I watched eagerly as it flew, whistling softly, toward the goalposts. It struck the one rope, caromed into the other, then landed, impossibly, into the baby swing facing away from the plate. I threw up my arms, celebrating the absolute impossibility of this achievement, feeling for a moment like Joe Carter. I had created a sport and I had beaten it. I turned to my kids, grinning idiotically; but of course their heads were down, kneading their purple sand. That’s the best and the worst thing about sports; they don’t matter. I left the ball in the seat, gathered the rest, and took the kids inside to eat some stroganoff.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now