photo: Keith Allison

Control

Rachael McDaniel

When I was born, Roy Halladay was 20. Now I am 20, and Roy Halladay is dead.

***

I wrote a lot as a little kid. I was overly energetic, frequently bored, always bouncing around, and writing was one of the ways I could expend that energy without hurting myself. I’m glad I wrote so much, because I wouldn’t remember— wouldn’t want to remember— the truth about how I felt about life as a little kid.

The earliest diary entry I have is from when I was six. I wrote, “Nobody understands me. Everyone in the whole world hates me. I am so alone.” There are tear stains on the page. And I know exactly where I was when I wrote it: curled up on the bathroom floor, where I did all my writing. Where I am, incidentally, right now.

Most of the entries are like that. I had a bad brain. I still do.

***

I don’t remember when I first saw Roy Halladay pitch, because I don’t have to. For my entire childhood, Roy Halladay was the Toronto Blue Jays. The Toronto Blue Jays were my brother’s favorite baseball team, and they never did very well in the standings, but I didn’t care. Because Doc was the entire team. He was the only one that mattered. And he always did well. As far as my young eyes could tell, he was always perfect.

It was hard for me, back then, to sit through an entire baseball game. I watched him, though, every start I could. I was constantly in awe. He never got injured. He never got tired. None of the other pitchers ever seemed go for as long as he did.

The most amazing thing about Doc to me, though, was the finesse with which he placed the ball, squarely in the catcher’s glove. He threw so hard, but located like he was painting with the tiniest, gentlest of brushstrokes. And when the batters did manage to get to him, he never seemed shaken. He never screamed or cried like I did. He was always in control.

I wished I could be like that. I so badly wanted embody what I saw in Doc’s pitching. My world was so chaotic: Everyone around me was in conflict. My own mind was in conflict. Everything was completely out of my control. I hated it. I wanted it to stop. But I couldn’t do anything about anything. I was just a kid.

So I would go out, a too-tall six- or seven-year old with a gross scuffed baseball and hand-me-down clothes, and throw against a fence, as hard as I could, trying to pinpoint a location in my imaginary strike zone. Exactly like I thought Doc would. I’d do it again and again for hours, until my arm hurt, and then I would keep on going until someone made me come inside. And I would be frustrated, because Doc wouldn’t have had to come inside. Doc always finished what he started. He always went the distance.

I don’t think I was ever happier than when I hit my spots.

***

I always tear up when I think about Roy Halladay. I tear up when they mention him on Jays broadcasts, when they bring him on the field for celebrations. I teared up writing a piece about his last game with the Jays. Because Roy Halladay gave my unhappy childhood the pure, transcendent joy of being in control. That feeling has always been what baseball means to me, truly, at its core. It’s the feeling I chase when I’m watching the sport, and it’s the feeling I chase when writing about it.

Doc is there in all the ways I interact with baseball. And when I need inspiration, when I feel myself spiralling, I always go back and watch his old starts. They were, until today, just as comforting as they’d been when I was six.

***

Until today, I’d never existed in a world without Roy Halladay. I don’t know what this means, and I don’t know what to do about it. I am writing about it, and crying, the same way I’ve always processed things.

But I can’t go and throw a ball against the fence. I’m too old for that. I’m not a kid anymore. I have no spots to hit. It’s November, and it’s cold, and I’m 20. And Roy Halladay is gone.

Command

Nicholas Zettel

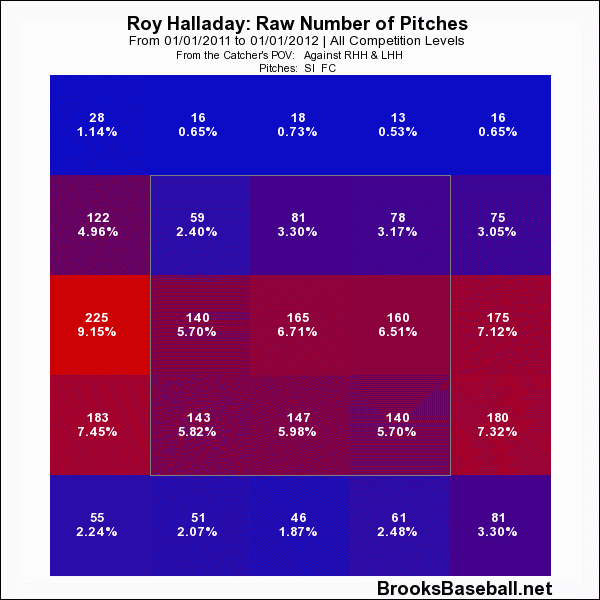

Roy Halladay had the best stuff I’ve ever seen. When I have to think through a puzzle, or grind through a challenge, I often run my mind through pitching sequences. How would I approach this? The fastball is always Halladay’s sinker-cutter blend. It’s the type of pitch that, if the stars aligned for one day and I could wind up, I would face a right-handed batter with no fear and ride that armside run and fall. Commanding that pitch would almost be too much to ask for. When Halladay’s ball left that hand, he could land that moving fastball to any area of the strike zone, and contort its edges. Here’s his 2011 plot from Brooks Baseball, a year I watched Doc work twice against my beloved Milwaukee Brewers:

Brooks Baseball calls Halladay’s primary moving fastball a cutter, but even that pitch ran armside, or “in” against right handed batters, from Doc’s hand. The plot above demonstrates what difficulty batters must have had against Halladay during that 233.7 inning, 2.44 Deserved Runs Average (DRA) season. While both pitches featured amazing armside movement, Halladay could land both pitches across the zone, and indeed did so with nearly absurd regularity; the pitch totals are symmetrical and methodical in a manner that describes a pitcher confident enough to attack the batter anywhere. More fascinating still is how Halladay used both pitches to generate missed swings and groundballs, the former from the glove side of the zone, the latter from the armside of the zone. As though Halladay needed any additional pitches, this middle-to-middle-low strike zone approach with the moving fastballs perfectly walled off breaking balls and changes of speed that darted just as sharply but lived exclusively off the bottom of the zone.

This compartmentalization of the strike zone should not take away from the organic beauty of those moving pitches from Doc. What I loved about watching him pitch was that his stuff seemed as unfair as a fireballer that rides in at 100, but Halladay wasn’t throwing 100. Those pitches just twisted and turned, outlining the zone, and moving in such a manner that must have felt like 100 factorial to batters.

Certainly there are purer pitchers in terms of velocity, maybe even better pitchers in terms of guile. Someone could easily bring up Greg Maddux. It’s especially tough to talk up Halladay’s stuff when his career overlapped with Pedro Martinez, who also morphed into a brilliant moving fastball expert and is on the short list for best pitcher in history. Luckily, Pedro’s success was just ahead of my time as an everyday baseball fan, so Halladay was it: the moving fastball, the best pitch in the game. To this day, I’ll take a scouting report with that movement over one with the fire; we’ll be lucky when we get to see the next complete moving fastball arsenal that allows us to invoke this comparison once more.

The Day Roy Halladay Cut Down Broad Street

Kate Preusser

Even if you’ve never been to Philadelphia, you’ve probably heard of Broad Street, but if you haven’t spent time in the city, you probably don’t understand its function: a ley line, a baseline EKG measuring the city’s heartbeat, the city’s nave and navel. Every year the Broad Street Run draws thousands of people to Philadelphia from across the country. The route starts in North Philadelphia, near where Broad Street proper begins (before it runs into Jenkintown, the first line of refuge from the city when white flight exploded in the 50s), and cuts straight through the heart of the city, ending at the Navy Yard. It’s just ten miles, but in 2010 that was long enough to span the two Philadelphias: from the bulletproof glass Chinese food places and the stately, shambolic Divine Lorraine Hotel of North Philly, straight down to the elegance of Center City: preserved Furness buildings and Golden Age architecture and the wedding-cake confection of City Hall. Citizens’ Bank Park pops up shortly after you clear Center City, signaling the end of the race is near.

Ten miles: it’s not that long for a distance runner, a matter of minutes down I-95. But in the school where I taught in North Philly, just a few blocks off Broad Street, it might as well have been Point Nemo. To be clear: there are vibrant, lovely school communities in the Philly public school system. And then there were ones, in 2010, that were labeled as “failing” under No Child Left Behind, full of young teachers like me, the bottom-of-the-listers who were reassigned to schools every year as budgets were cut, where the drinking fountains didn’t work because the old pipes had contaminated the water, where you’d pull a ream of paper from the supply closet to find it covered in mouse droppings.

Meanwhile, just a few miles down Broad Street but what felt like light-years away, the Phillies had played good baseball all summer, led by staff ace Roy Halladay, whose perfect game the past May I had watched in a bar (I didn’t have cable at my apartment) that offered dollar Yuengling pints. I high-fived the bartender after the last out. Phillies Fever re-infected the city, the outbreak powerful enough to reach us all the way in North Philly. There’s something about the playoffs that will draw even nonbelievers into the church of baseball, and there was something about Roy Halladay with his big, pigeon-toed leg kick and easy smile and the way he could make batters look so foolish. Pitching isn’t always the easiest skillset to sell kids on, lacking the drama of big home runs and showy athleticism, but they liked Halladay; it was impossible not to like this man, who’d chosen to come to Philadelphia above all other places. I printed off copies of newspaper articles about him and called it reading practice. “He looks nice,” opined a student over a copy of the Daily News I’d brought in. I went to agree, but she continued. “Not like most white people. He has a nice face.” Then she looked at me, apologetic. “No offense, Miss. You have a nice face too,” she said kindly. “That’s why they’re so mean to you.”

The Phillies didn’t win the World Series that year, and I didn’t become magically good at my job. This isn’t that kind of story. But I did get involved with a program that trained Philly public school students to become distance runners, and we entered the Broad Street Race that spring together, and I crossed the finish line with a student who just three months prior had been suffering from asthma and using an inhalator. And all that wouldn’t have been possible without an idea I had when I left school early on that Wednesday in October for Halladay’s start in the NLDS, headed to a bar by school, and toasted to him over dollar Yuenglings every inning of his no-hitter, when I realized this thing he was doing was taking place just blocks away from where I was at that moment. Of all of Roy Halladay’s feats, making Broad Street shorter might be the most impressive.

The Opposition

Mary Craig

The Red Sox had clinched the Wild Card the previous night and thus the lineup was filled with Trivia Night bonus names like Joey Gathright and Rocco Baldelli. The game–between the playoff-bound Red Sox and fourth place Blue Jays–was just about as meaningless a September 30th game as one could design, but for one element: Roy Halladay.

The vast majority of his starts were events, and regardless of the outcome, you just felt lucky to have been able to watch him pitch. Or, at least, that’s how most people viewed him. For me, a Canadian Red Sox fan, Roy Halladay was no less than a constant itch on the bottom of my foot. When he wasn’t being brought up in trade rumors, he was rendering Red Sox bats so futile they may as well have been match sticks, and when he wasn’t doing that, he was negotiating with bank robbers. During the latter part of the 2009 season, he was everywhere.

And that September contest was no exception. Everyone expected him to do well against the Red Sox Junior Squad, but his performance, like his being, exceeded all expectations. He threw his second straight shutout and recorded his ninth complete game of the season, doing so on an efficient 100 pitches. The thing about Roy Halladay was that his dominance was so matter-of-fact it was almost easy to overlook–he preferred a simple groundball out to an epic showdown, commanding the mound each game for as short a time as possible. In many senses, he was a throwback pitcher, but there was also something novel about him.

It was a school night, and so I couldn’t allocate the typical 3+ hours of my time to watch the Red Sox. Perhaps it was because of this time crunch or because the game was so meaningless, but it was the first time I truly appreciated Roy Halladay mowing my team down for 2.5 hours. It was efficient, skillful, and fun. I chuckled when he struck out Ortiz for the third consecutive time, and I cheered when he recorded the final out, not solely because it meant I could go to sleep, but because it was a genuinely beautiful game.

Over the next several days, I saw more people at school wearing Halladay jerseys and shirts than I had seen in the combined past five years. No longer was the school a clash between a handful of Red Sox and Yankees fans with hockey jerseyed onlookers. A real, actual baseball culture was developing, all because of Roy Halladay. I finally had three-dimensional people with whom to discuss the sport and to whom I could explain the understated brilliance of Roy Halladay.

Roy Halladay was always a pitcher whose whole was greater than the sum of its parts, which is something I learned in those two-and-a-half hours on September 30th.

Promise

Matt Sussman

Roy Halladay ascended to the Blue Jays roster in 1998 amidst a strong pitching staff. Roger Clemens, Pat Hentgen, Chris Carpenter, Woody Williams and Juan Guzman assembled the third-best ERA in the American League. They couldn’t quite catch the Red Sox for the Wild Card, but they did give the 21-year-old Halladay a taste of September.

In his second major league start, the final game of the year, he faced the last-place Detroit Tigers. A get-the-season-over-with game turned into must-see TV as Halladay took a no-hitter deeper and deeper. Dave Stieb had the team’s only no-hitter ever (and still does), but it wasn’t at home like this one.

The Tigers went down in order through the first four innings. All the while, the Jays seemed to go through their pre-game motions of subbing out regulars like Tony Fernandez and Carlos Delgado, because that’s how you roll on Game 162. A fifth inning error downgraded the game from perfect, but the outs kept piling up through the fifth. The sixth. The seventh. Somebody at ESPN poked a sleeping producer with a cattle prod and started giving score updates to a nation without cell phones. The eighth inning was a breeze. He had a 2-0 lead going into the ninth. Gabe Kapler lined out to left. Paul Bako grounded out. This was supposed to be it. On the final vignette, pinch hitter Bobby Higginson spoiled the conclusion with a solo home run. Halladay got the next batter out to win 2-1.

Go back and listen to the crowd jubilation on the home run, and notice how it changes to exasperation. No-hitters are white whales to some of the game’s best, and who knows if he would ever throw one again. (He of course did: a perfect game with Philadelphia and a postseason no-hitter after that).

Halladay had a great family, a swell fanbase, an indelible run as a pro athlete. He had just bought a plane, extending his freedom to pursue his charitable passions and his own leisure. Occasionally when something just starts to get good, it ends abruptly and without explanation.

Heat Stroke

Trevor Strunk

Earlier tonight I wrote a long and heartfelt tribute to Roy Halladay the man and the player, and I think I did a good job. Completely wrung out of emotion, I wanted to come to Short Relief to tell the story of seeing Halladay at his famous “heat stroke” game.

Ah, you don’t remember the heat stroke game. Well! I’ll paint a picture: the year is 2013. Rahm Emmanuel is disappointing millions with weirdly conservative policy and privatization schemes. Jay Cutler fever is spreading. And the city of Chicago was just learning about an upstart team called the “Cubs.”

I was living just a few blocks away from Wrigley Field, which was exciting on game days because I got to ride the train and pretend I was a sardine or a very avant garde tiny-home-owner. But beyond the crowds of dark blue that made getting home an enterprise, there was of course baseball to be had, and Phillies baseball at that. So every year, I’d make sure to go to one of the Phillies-Cubs tilts at Wrigley, and this year I picked a doozy.

The starter was Roy Halladay, and it promised to be a great game, even though both teams were effectively out of the race. It was August 30th, and neither club had more than 62 wins. Nevertheless, a game is a game, and we had nosebleeds, which at Wrigley are kind of charming. Less charming was the weather: 91 degrees, with the pavement and proximity making it feel like 119. We were sweltering, and everyone on the field was too.

Fortunately, we ended up next to the Women’s Volleyball coach of Ole Miss University and his pals, one of whom taught Nate McClouth in elementary school. And yes, before you ask — they could have been lying, for sure, but I think I’ll forgive them if they were because my word those are whimsical fibs.

They bought us beers, let us in on their gambling, and overall showed us a wonderful time in the heat. Roy, on the other hand, wilted, coming out in the sixth with what looked like a serious injury. My stomach sank.

As it turned out, it was only heat stroke — not that that’s nothing — and not a UCL or a broken arm. The Phillies ended up winning (not that it much mattered) and we bid adieu to our friends. The next day, I realized I’d shared an experience not just with my wife or those random fans, but with Roy, who was as hot as I was and was suddenly mortal as a result.

I don’t pretend that this makes me closer to him or somehow more impacted by his tragic passing. But there is a way in which we can somehow feel acquainted to people who are so much larger than life, even if we’re watching them from a seat 60 feet higher than they are. I’m gonna miss Roy, but we’ll always have hot, sweaty Chicago.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now