Time is a Serpent Eating Its Own Tail

By: Emma Baccellieri

Participating in baseball’s Hall of Fame season requires establishing a friendly relationship with baseball’s history—watching players from the past, putting them in context by reading about the past, calibrating standards by analyzing elections of the past. The whole thing is predicated on looking back. And yet, despite that, the process is decidedly not nostalgic. The past serves as the source material here, but the past is not the point. The future is the point. The purpose of the exercise is deciding who is guaranteed space to survive in baseball’s collective consciousness and who is left behind: who gets to live forever and who ends up forgotten. It’s drafting the future of the sport’s story by looking at its past through a selective lens of the present, a relationship with time complex and fundamentally somewhat unfair.

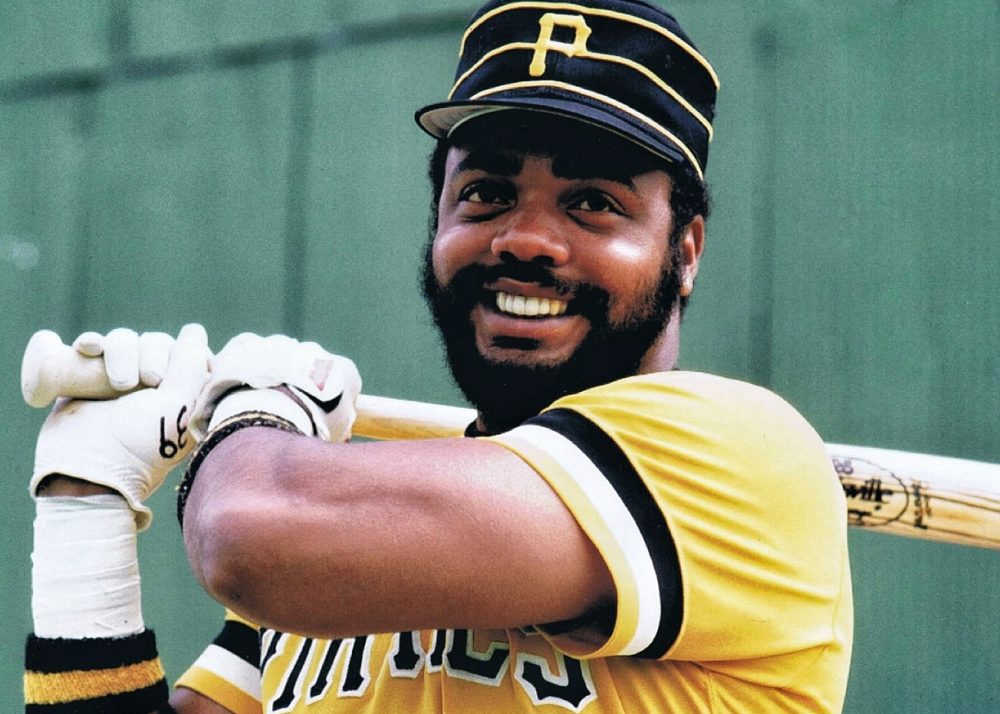

On the subject of time and complex things that are fundamentally unfair: there is this technique seen in writing and talking about Dave Parker, on the modern era ballot this year. It goes like this. First, you are called to remember Parker as he was in his prime. To remember him hitting the cover off the ball, getting the runner at home from deep in the outfield, generally being so dominant as to earn the title of baseball’s first million-dollar player. (This part is par for the course in Hall of Fame reflections. This part is normal.) And then, you are called to look at Parker as he is now. He has Parkinson’s disease.

I understand why people use this technique. It’s effective: sentimental without being sappy. It’s also dishonest. Parkinson’s has everything to do with time, but it has nothing to do with this blunt binary of a glorified before and a miserable after. That’s not really the nature of a progressive condition with a deeply uncertain timetable. Every Parkinson’s diagnosis is different—they say, over and over—and so there’s no secure framework for any future, which means that there is no conventional understanding of time that can carry the meaning that it once did. The only guarantees for the years to come are that it will get worse and it will not go away. But it could be very slow or very fast or any of the maddeningly vague possibilities in between, and so there isn’t much that you can hope for other than a present that expands to take up as much space as possible. Maybe this is the last Thanksgiving where you can pretend that it’s normal without any effort; maybe there are a few more of those, and then a few where you can pretend that it’s normal if you really try to lie to yourself, and then a few where you have learned to stop lying. Maybe this is the last Thanksgiving, period. That sort of thing.

There’s an argument to be made that Parker was once the best player in baseball, if only for a little bit. From 1977 to 1979, he seemed like he could maybe become one of those players who earns a lucky pass to escape the ordinary process of being forgotten. But the window shut quickly; other things happened, the relatively brief moment of that brilliant present collapsed into a longer and less satisfying future. He didn’t make it into the Hall of Fame in 15 years on the regular ballot, and he very probably won’t make it this year. The Hall will not remember Parker. Let it; it has no jurisdiction over us. His immortality is ours, to wear whatever shape we wish, in whatever time.

Jose Bautista’s House Has Many Rooms

By: Kate Preusser

© Winslow Townson-USA TODAY Sports

If you are on Twitter and have tweeted about baseball even once, there is a good chance that you are one of the 996,000 accounts followed by Jose Bautista. It’s gotten so that it’s almost a mark of pride in baseball twitter to not be followed by Bautista’s account, which follows everything from the usual MLB suspects to a woman in London who hasn’t tweeted since 2016 whose account has exactly two followers: her daughter and JoeyBats.

In an interview with For The Win in 2015–back when his account followed a mere 492,000–Bautista explained his approach to social media: “I feel like I need a team of people supporting me. Social media is a big part of that. I want to make sure that the fans can get to know me…if you talk about baseball, if you talk about me, the Blue Jays, MLB, if you kind of help grow the game and create awareness, my team follows you. All those things that I want to talk about and I normally do, if other people talk about it, my team is gonna follow you.”

Bautista is upfront about the fact that it’s his team controlling the account, although doing it from his direction to help grow the game. He wants baseball to be a bigger conversation, and understands that the way to do that is to invite more people into it. Even for those acquainted with Bautista’s social media strategy, there’s an undeniable initial thrill in being a Twitter Nobody followed by a Twitter Somebody:

For every Colleen, though, there is the harsh reality of a Mark:

It’s Hall of Fame Season, which means it’s time for the annual Small Hall – Large Hall debates. Those who champion seemingly “fringe” candidates will craft arguments around advanced stats and the need for the Hall to adapt to modern baseball (like inducting a DH, for example), and those who believe they have a sworn duty to protect the exclusive sanctity of the Hall of Fame will argue that it’s not the Hall of Very Good. So far, the Marks are besting the Colleens, as there’s been an exponential decrease in players born post-1950 inducted into the Hall. We’ll have to wait to see what happens when writers go to vote for players who follow them on Twitter.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now .

.