We like our decisions based on precedent. Precedent is undoubtedly what agent Scott Boras tries to present to owners in a 75-page book outlining the merits of signing Jake Arrieta. “I give them all the book, and the onion starts to peel,” Boras said this week. “And all of a sudden there’s only a small group left who do what [Justin] Verlander, Arrieta, and [Max] Scherzer do.”

Within both his paper-bound appeal to power and his “offhand” comments–sure to be remembered more distinctly than anything in the screed–are nods to the cases he wants associated with Arrieta’s name. Like any good litigator of subjective domain, he’s highlighting touchstones that can be true and persuasive, while hiding less appealing true and persuasive things behind his back. And that’s OK. Boras has proven that his personal appeals and grand gestures and occasionally wayward logic are effective means of maximizing his client’s income, which we’re all for.

What he, understandably, doesn’t do is acknowledge when the precedents are harder to come by, slipperier to pin down, which is very much the case with Arrieta. Of all the recent big-ticket free agent pitching cases to hit the market for dissection and eventually judgment, of sorts, Arrieta’s will say the most about how we interpret our newest data sources, and just how ready we are to stake fortunes to their insights.

I’m not sure when it became apparent that Arrieta’s brand of dominance was destined to be discussed–something to be believed or not. It was probably after that second no-hitter. It didn’t seem like he was 2015 Arrieta anymore, but … no hits. It may have been even before that. During Arrieta’s mind-boggling 2015 season, when he netted the Cy Young award that likely features prominently in Boras’ book, he struck out only 9.3 batters per nine innings and allowed contact on 84.4 percent of swings in the zone. Both very good, to be clear, but not indicators that would make you exclaim, Goodness, there must be a sub-2.00 ERA attached to this!

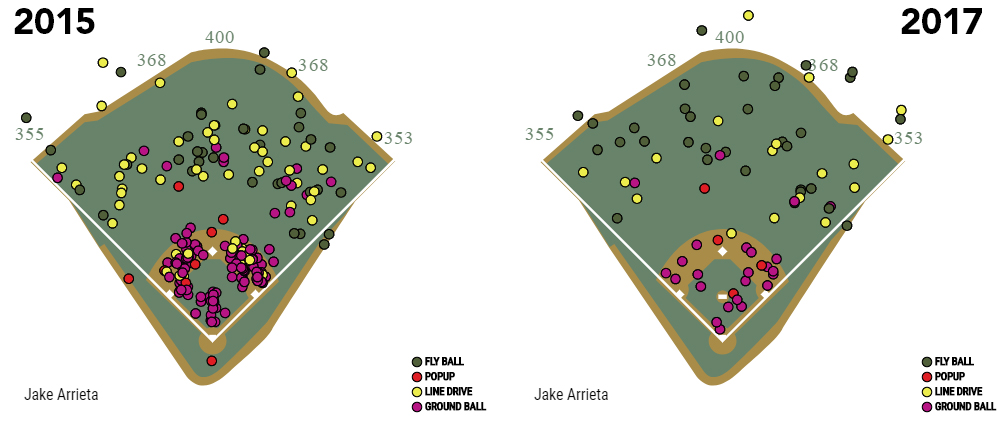

In the first year of publicly available exit velocity data, Arrieta was a perfect storm of sliders and sinkers and weak grounders, forcing us to wonder if the idea of contact management, or soft contact, filled in the gaps left by our standard methods of evaluation. As is typical with pitching, we didn’t really get a chance to find out. Things did not continue apace. His control and command wavered, especially with the slider. Despite the no-hitter, 2016 brought regression that DIPS theory, blind to contact quality, would have led us to predict. And 2017 saw the backslide continue.

The contemporary information inundation is unquestionably a positive for any number of reasons that I don’t need to enumerate on the digital pages of Baseball Prospectus, but it also tests our mental discipline: Maybe Justin Verlander’s pitch data points to decline, but maybe it points to a correctable physical issue. Maybe Zack Greinke’s pinpoint strike-stealing skills are diminished, or maybe they got muddled in the complex tango of joining a new club in a new park with a lesser catcher. The fact that each season’s data set is heftier and more granular doesn’t mean it should drown out last season or the one before any more quickly.

For almost every exhibit portending Arrieta’s decline into mediocrity, it’s possible to summon reasonable doubt.

The most worrisome sign of decay is his slider usage. As Eno Sarris posited in 2016, Arrieta has struggled to spot his slider and its cutter-like variation. Instead of pounding the low-and-away corner against righties, he’s missing up or in the dirt.

As you might expect, he’s responded to this loss of command by going away from the pitch. After wielding it 29 percent of the time, to devastating effect, in 2014 and 2015, Arrieta used the slider less than 19 percent of the time in 2016 and then only 14 percent of the time last season. And even with hitters getting fewer looks at it, they have been more and more capable of laying off.

In 2015, Arrieta was forcing hitters to end plate appearances on that slider. Almost 38 percent of the balls put in play against him came off it, and resulted in a paltry .186 AVG and .270 SLG. Only 16.5 percent of balls in play came off the slider in 2017, and the results reflected the greater selectivity hitters were afforded by wildness. The contact wasn’t noticeably harder, though. Arrieta allowed an average exit velocity of 83.9 mph on the slider, still better than average and only half a tick worse than 2015. It was simply in the air far more often, which might speak to how much of the pitch’s problem is tied to location.

It could also hint at the progress hitters have made at countering low and downward breaking offerings.

Then there’s the sinker. In 2016, it took a hit as the slider became less of a threat. In 2017, it took a hit from diminished velocity. But, Arrieta also might have unlocked something with it. Sometime around early July, he ramped up usage of the sinker and committed to two basic spots on the heatmap: Up, breaking away from lefties, and down and away, breaking in toward righties.

Here’s a data point on what that elevated sinker can look like against the lefties who account for most of the gains the league has made against Arrieta:

It’s a hellacious. Even blocking out the filthiness of that specific pitch, the idea behind that location seems to be a smart one. Elevating it will mitigate some of sinker’s velocity decline, and steer clear of the nitro zones for most lefties. It’s not going to make up for the loss of the slider’s effectiveness. Nevertheless, from July 1 on he prevented hits at his usual elite clip (.204 AVG), and he made balls in play a poor proposition for his opponents (.234 BABIP). He didn’t have the whiffs of old, and there were still more homers involved than you’d want, but it was an adjustment that made the most of what he had.

This is why we have to wrestle with the complex beast of his track record. An inability to wrangle the slider almost certainly threw off the overall use of his sinker and caused his overall results to sink. The original reason for skepticism, Arrieta’s possible contact-management skill, is an amalgam of all these other abilities and tendencies. Like fickle homer prevention numbers or the command and control abilities for which BP has created metrics, we are still learning how to feel about Arrieta’s most salient selling point. It’s tempting to observe his return to earth and assume he will soon crash into it, but Boras will, smartly, use his pulpit to remind us how he reached such heights.

And so you go to your mental scales.

There’s no guarantee he ever regains command of the slider. Even if the velocity rebounds a bit in 2018, we can’t expect an over-30 pitcher’s fastball to go anywhere but down. The strikeout rate dropped in 2016 and we shouldn’t count on improvement without the slider returning to prominence.

Still, the sinker remains a weapon, and in our most recent extended look at Arrieta, it was being deployed effectively. Even with the noted negative changes in his profile, he remains an excellent preventer of hits. His issues have not managed to keep him from posting better-than-average DRA numbers. The same can be said for the crude results of ERA, by the way. And finally, there is the great, big, unavoidable question mark of hope: It could all come back together. There is precedent, right? Just recently, the personal “it” factors for Justin Verlander and Zack Greinke and Dallas Keuchel have just … reappeared to varying degrees. It could happen for Arrieta, couldn’t it?

We have looked askew at murky brands of greatness before, and wondered whether that ability to get called strikes could really persist, whether that velocity gain is sustainable. Often, our skepticism is justified. But Boras, through Arrieta’s current availability, asks a hard question: Are you sure it can’t happen again?

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now