Baseball Pros, Counterculture Baseball Game

By: Matt Sussman

There are two categories of NES baseball games: ones who have heard of MLB and ones who haven’t. Perhaps the oddest one I’ve come across is Quattro Sports, which is actually four games, but one of them is titled “Baseball Pros.” This was released in 1990 by Codemasters, which among other games put out a really underrated Micro Machines game the following year. Their most disruptive video game contribution was the Game Genie, which may explain in great detail how Baseball Pros basically warped the reality of the national pastime in a much subtler and more destructive way than Base Wars ever could.

The game has preset teams in RBI Baseball fashion; a lineup, four bench guys and four pitchers. The teams are all around the world, including on-the-nose stereotype teams such as Mexico Sombreros, London Royals, Berlin Brewers, Australia Boomerangs, Peking Dragons, and Hawaii Volcanoes. There should be no disputing where these teams are from.

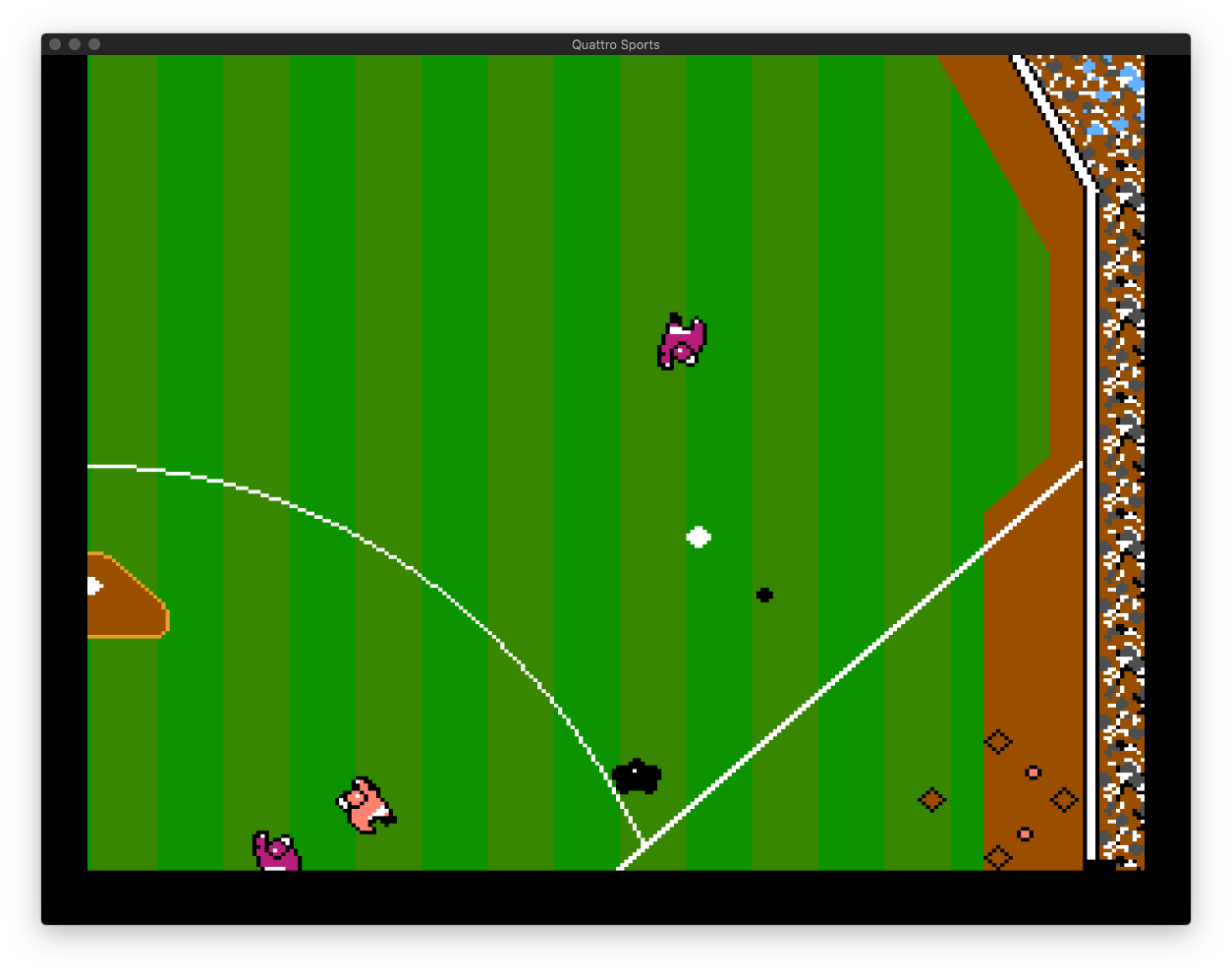

To its credit, the game music slaps and most of Codemasters games do this. The fielding display is horrendous, and the ballpark basically has that gawdawful Fenway Park right field on both sides. The primary issue is that all fielding and all baserunning are done by CGI athletes who are terrible at it, and therefore the pitching is also bad (unless you are a strict FIPologist). Most of the infield is already covering bases, leaving only the pitcher and the other middle infielder to rove. The outfielders move but only once the ball gets sorts close to them. Basically the batting average in this game is way over .500.

But the slugging is also .500, because the baserunners are so slow, legging out a double is near impossible. Hit it directly to an outfielder and you’re toast. I ripped a ball off the left field wall and the fielder still threw me out at first. Outfield putouts are common, because it takes about six seconds to run to first. Your average Molina can do it in under five.

They changed some other rules as well. For example, the only force play is at first. You can advance on a fly ball before it’s caught. And games are 10 innings, because some programmer who has never seen baseball probably thought nine was a weird number to end on. They might be right.

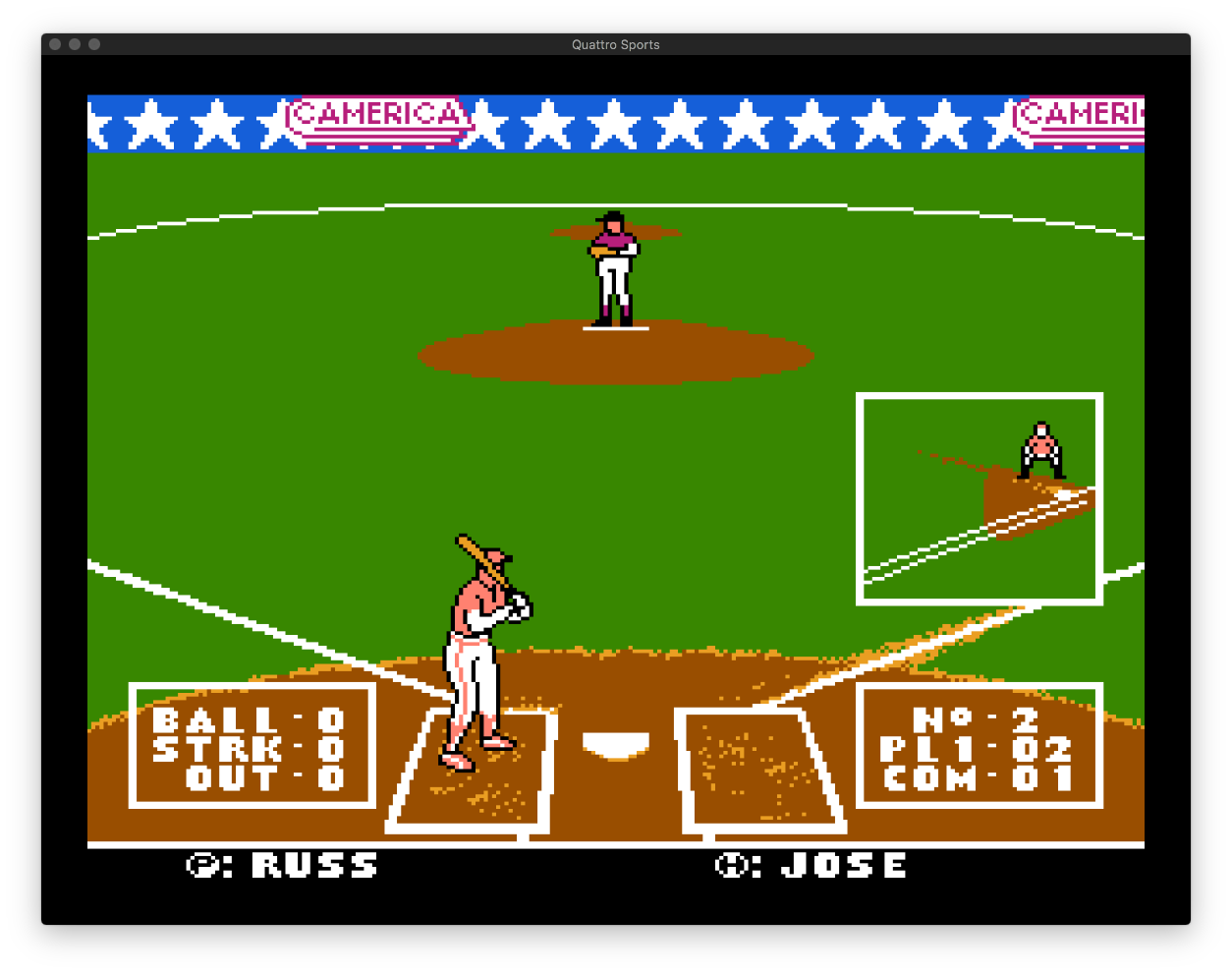

I played the Mexico Sombreros against the Moscow Bears. First of all, the Moscow Bears has a pitcher named Russ. I’m not even mad at that one. But as you pile up the innings of crooked numbers, your main game is just to keep hitting singles then hope someone knocks it into the crowd. There’s no reason to switch pitchers unless you’re Tony La Russ and just *have* to.

The game was 22-22 after 10 innings, and after grounding into my fourth bases loaded double play (which of course, starts at first, then to home), I realized that on the ground balls, I shouldn’t run on them. But I *should* run on fly balls. They switched grounders and pop-ups. They did it, those sons of guns.

But in the bottom of the 11th, the Bears scored their 23rd run of the game to win. Except … it wasn’t a walkoff. I had to finish the inning in demoralizing fashion.

Either Codemasters completely broke the game of baseball, or completely fixed it. Either way, since they buried it in a 4-in-1 game, nobody noticed.

Life Expectancy

By: Patrick Dubuque

For no good reason recently, I thought about one of my favorite statistics, RE24. Actually, RE24 isn’t a statistic so much as a chart: take the base state, take the number of outs, and it’ll tell you how many runs, on average, a team will score before the inning is over. What RE24 will not do, not even pretend to do, is care who the hitter is, or the pitcher, or try to distinguish between Billy Hamilton and Billy Beane out on second. It just gives you a simple, rounded baseline for what happens on average when you’ve reached that point.

I’m the sort of person who likes baselines. This is not a virtue. Some people look at a task in front of them and think: “what do I need to do to get this right?” I will look at that same task and ask myself “what do I need to go to exactly meet expectations?” It’s not laziness, or at least not primarily laziness. It’s pragmatism. I don’t want to do more than necessary because there is more to do, always more. I don’t have the luxury of being a perfectionist.

Because of this character flaw, I like nice round estimates. I like to look at the little dots and numbers on the corner of the chyron and think, “the pitcher is in (this) much trouble right now.” It’s not limited to baseball. I do this with football, recalibrate the odds of a field goal as the team moves down the field, consider the third down conversion rate based on yards to go. I do this with the grout in my shower. It’s quick, it’s easy, it’s good enough.

But as Mr. Ellis has been writing his notes toward mediation, and I’ve been editing them, I’ve come to think about the forces that have helped me develop the way I see baseball. And I wonder if I like RE24 for the very same reason that limits its usefulness: I like how it strips the humans out of the equation, averages them all to a blurry paste. I think it’s the averaging that appeals to me.

Thanks to the low kids-per-square-mile of my childhood neighborhood, my baseball often arrived through a screen rather than some idyllic, uncut field. And that video game baseball, in my era, often looked like this:

The graphical and programming restraints of the time were the ultimate form of democracy: each player looked and performed the same. It wasn’t until RBI Baseball in 1987 that players got names and varied in abilities; the first accurate face arrived somewhat later. There is artistry in limitation, as Twitter users learned with their 280 characters; early video games were forced to employ symbolism when they couldn’t render life perfectly. Or at least, they were able to render the simplified, solid green simplicity of childhood.

I was a small, nerdy boy; the anonymity presented by Nintendo baseball was a comfort. I had more individuality than I needed; all I wanted, my entire childhood, was to not stand out. Maybe that’s why I feel distaste at watching pitchers hit, or why my favorite players are the most forgettable, or well-rounded. And maybe that’s why I like knowing that a runner on third with one out should score 0.865 runs; that feels fair. That way I’m not blinded by the name on the jersey, expect perfection or adopt cynicism. I haven’t pre-written their story. They’re just everyone, a few blurry pixels, until the moment they swing the bat and become a hero.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now