The Other Greatest American Hero

By: Patrick Dubuque

As someone who stumbled into adolescence in the year 1990, I can assure you: it was a frantic time. The Cold War was over, and two generations of Americans confident in their place in a two-superpower world found themselves untethered. Instead we had a thousand points of light, and nobody knew what the hell those were, but it sounded difficult and vaguely Star Wars-themed. Popular culture reflected this sudden schizophrenia: The corny, comfortable eighties ground to a halt, with its measured synth drums and its carpeted, fireplace-framed living rooms. Alf was canceled.

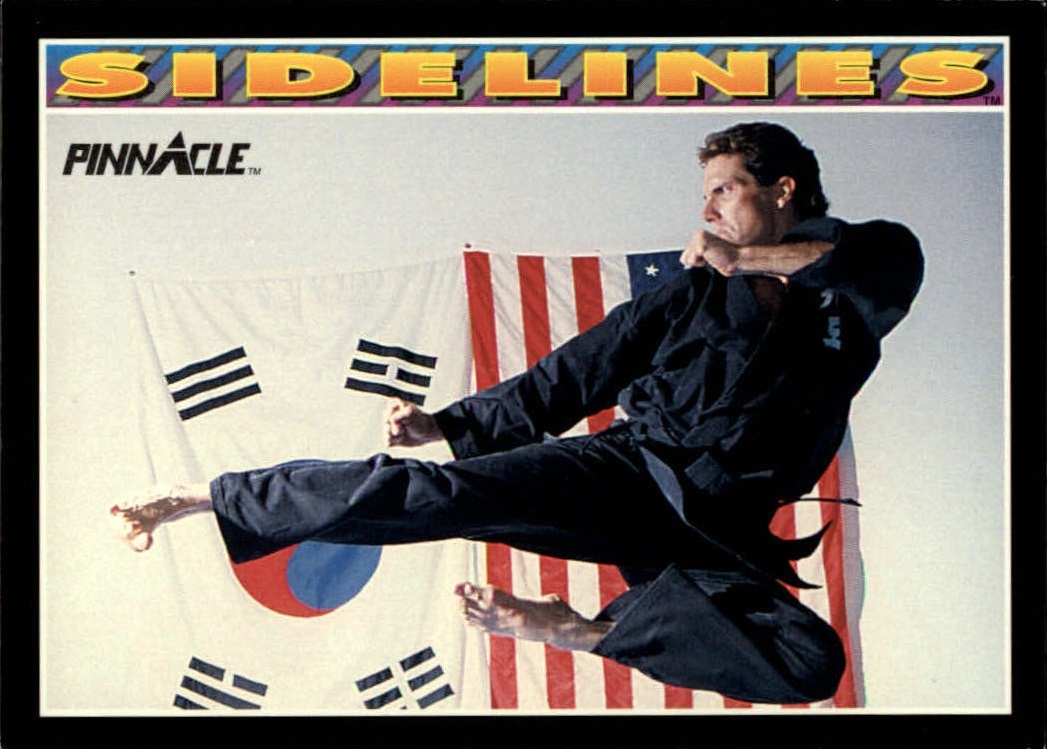

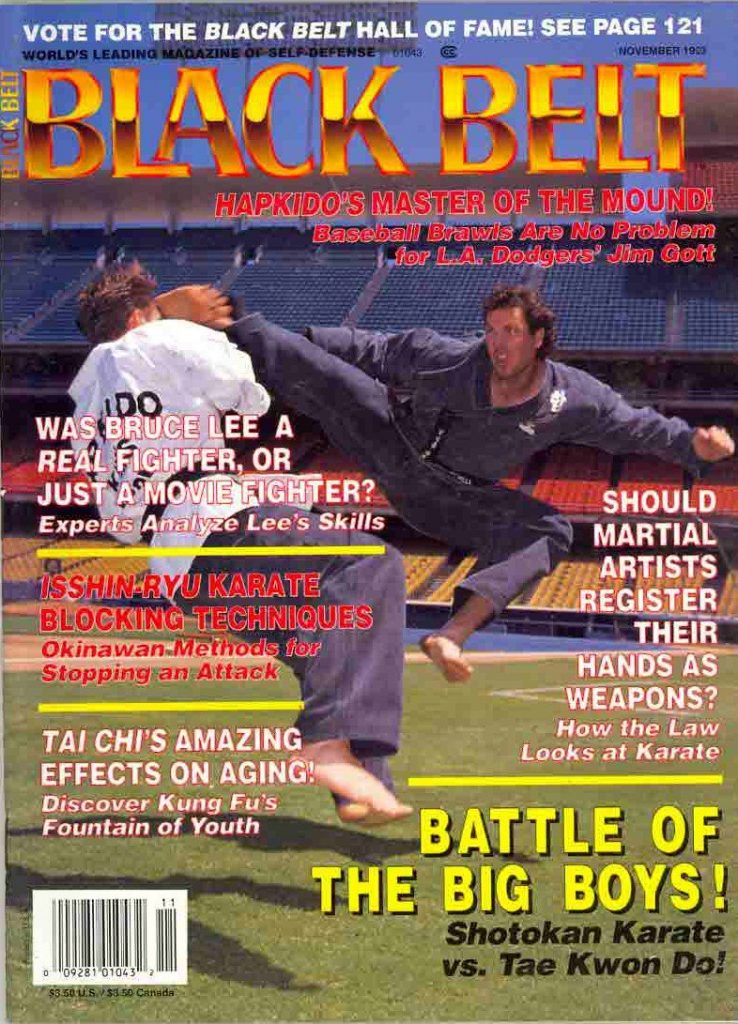

It was chaos, a cultural convergence zone. Turtles were suddenly ninjas and ninjas were apparently surfing children. Cops were rocking. Football players were playing baseball and baseball players were wearing football pads. Vanilla Ice snuck into national prominence somehow; that part is still a little hazy. There was a lot going on, so much so that we never really got a handle on this:

Jim Gott, a major league baseball player, was also a black belt in hapkido. That this failed to become a Saturday morning cartoon is a blow against Aquinas’ proof of the existence of god. The premise writes itself: Gott, between stints of his day job pitching middle relief on days the Dodgers are down by a couple runs, teams up with some kids from the local school: kids with attitudes, yes, but also with hearts of gold and fists of steel. Together they team up to solve nonviolent mid-level crimes, the kind where Jim Gott can punch a guy without having to worry about them just pulling out a gun and shooting him. Smugglers, say, or bank robbers. Or maybe robots, so Jim Gott’s fist could make them explode. Robot bank robbers.

Plus: all the baseball-related catchphrases a hack writer could ever want. This show would have been so easy to write that it’s amazing a computer somewhere hasn’t already accidentally produced it.

There’s no shortage of adventures that Jim Gott and the Fists of Freedom could go on together, learning valuable lessons about teamwork and the importance of keeping your arms up while roundhouse kicking. That we were denied this can only be interpreted as the first hint that America had lost its way.

(hat tip to Matt Gelb for bringing this to the author’s attention.)

Unhappy, Wants to Talk

By: Jason Wojciechowski

Christian Yelich unhappy with Marlins moves, wants to talk, says Jerry Crasnick.

Yelich: I’m unhappy with our moves, Mr. Jeter. I want to talk.

Jeter: Okay. That’s fine. You’re one of the game’s top young stars. You’re the best player we’ve got left. I think I can do you the very minor courtesy of listening to what you have to say. Go ahead.

Yelich: I’m not happy about the moves, sir.

Jeter: Alright. What about the moves?

Yelich: Mainly, the thing is that I’m not happy about them.

Jeter: … Right. Is there something in particular about them you’d like to say?

Yelich: Sir, I’m displeased.

Jeter: Is―okay? But can you elaborate?

Yelich: Mr. Jeets, the moves made me feel … well, it’s hard to put in words.

Jeter: Go on, son.

Yelich: I think it’s that the moves, sir, they don’t make me feel good. They make me feel bad. They make me not happy.

Jeter: …

Yelich (NODDING SOLEMNLY): Unhappy, I’d say.

Jeter: I think we’ve covered that ground.

Yelich: Yes, sir. So what I’d also like to say is that this unhappiness makes me want to talk.

Jeter: Good, okay. I’m glad you’re bringing this to me. Talking is healthy. So: What about it do you want to talk about?

Yelich: The moves, sir. They haven’t made me happy, and that’s what I want to talk about.

Jeter (LOOKING AROUND CAUTIOUSLY FOR CAMERAS): Is that right.

Yelich: It is, sir. It’s exactly right. These moves, and my feelings about these moves, well, it’s what I’d like to talk about, because they’re not sitting well with me.

Jeter (PICKING UP PHONE AND DIALING MICHAEL HILL’S EXTENSION): …

Yelich: Sir.

Jeter, while the line trills, with resignation: How do the moves make you feel, Christian?

Yelich: Not good, sir. Unhappy, even. Thank you for asking.

Jeter, hearing Hill finally pick up the other end: Michael, I have Christian here in the office with me.

Jeter (LISTENING): Uh huh. Uh h—what? Why are you laughing? Nono, don’t ha—

Jeter (STARING AT THE RECEIVER): He did that.

Jeter, (BACK TO YELICH, CAUTIOUSLY): Is there anything else?

Yelich: Well, sir, there’s just something I’d like to tell you about these moves.

Jeter (HEAD IN HANDS): Please, do go on.

(Scene.)

Notes Towards Mediation: Holiday Edition

By: Matt Ellis

So we’re a couple of days away from Christmas, and Hanukkah ends tonight. There will most likely be huge dinners, missed flights, uncomfortable beds in guest rooms, and horrific conversations about politics with family (on both sides). Nevertheless, I thought it might be interesting to close out 2017 in this series on baseball and media with a simple list of Two Things To Check Out, which will be referenced further throughout the rest of the offseason. Whether you are flying, trying to sleep in the basement of your brother Jeff’s midwest condo, or simply avoiding conversation, here’s some fun to put in your ears until 2018 graces us.

MLB Radio Broadcasts. archive.org, 1934-1973

I’m going to have a deeper post on the history of radio and baseball in the coming year, but for now this amazing trove of radio-broadcasted games provides a fascinating look into the history of the way the game was being mediated through one form in the 20th century. Listen to the difference in cadence from that Yankees/Tigers game in 1934 to the Mets in the 70s–the slow, eventual loss of crackle in the sound sent over the airwaves. Terminology–the way, arguably, player names come to be replaced by a description of spatial field mapping by the announcer, a transition wholly indicative of the shift from the contained assembly lines of Fordist production to the decentered and dispersed 1970s global markets. Mostly, listen to hear what has changed–and what hasn’t–in the process of mediating something that otherwise seems so difficult to represent.

1952 World Series Game Seven, Youtube

MLB Network always marathons Ken Burns’ Baseball doc over the holiday break, and while yes, obviously most of us reading this have seen at least forty-seven minutes of it each December for 20+ years, it’s 2017. YouTube hosts a number of classic games–not just the Pujols WS or Buckner’s error, but classic deep cuts you probably can’t even remember from the top of your head–and at the very least, they make for good background notes to mute other noise.

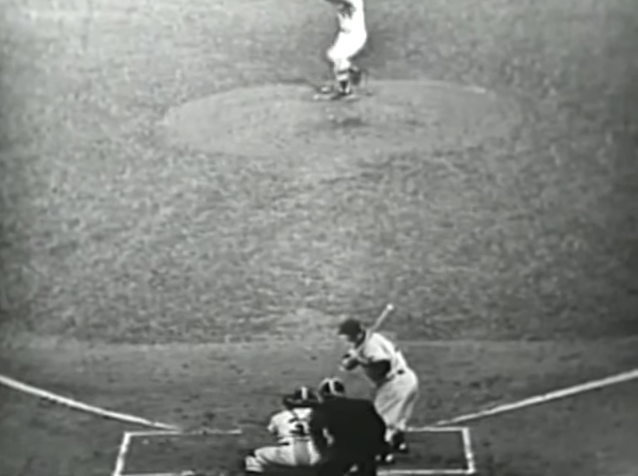

It’s more than a dusty historical relic though, it tells us something about the history of baseball mediation through its formal construction. Watch: the broadcast opens by introducing the starting pitchers for unaware audiences, and yet, despite our access to lineups on Twitter or schedules predetermined through newspaper reports and radio, this same introductory practice continues to this day on Root, Fox, TBS and the like.

Also take care to note the multiplicity of camera angles: your brain might be producing that image of one huge-ass single camera filming a contained live studio space of an I Love Lucy or something, but as early as 1952 there were already at least ten cameras covering the field for national baseball games. And perhaps, most importantly in a topic I will cover later–note the complete opposite camera angle for at-bats than what our contemporary moment provides for us!

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now