In Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay “Self-Reliance” he wrote: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” It’s often presented without the phrase after the comma, which is okay. Sometimes people drop the word foolish, which is not okay. Let’s stick with the shortened “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

There’s nothing wrong with doing something consistently, if it makes sense. It’s when the consistency becomes foolish that one displays a little mind. Mowing the lawn every week during the summer is consistent and not foolish. Mowing it in the winter is consistent and foolish.

What made me think of this, as you might guess, is Dusty Baker.

When the Nationals announced Baker’s firing, a lot of Baker discussion ricocheted around the internet. Some was fond. Some wasn’t. This article, deep from within BP’s archives, made the rounds.

It’s from March 2004, after Baker had completed his first year as manager of the Cubs. This was nearly 14 years ago. For those of you who’re at least, say, 38 years old, think back to March 2004. What were you like then, professionally? Probably different than you are now. You’ve learned some lessons, some of them hard. You’ve let go of ideas that proved to be wrongheaded, and adopted new ones in their place. You haven’t fallen prey to foolish consistencies.

But Baker’s never been able to fully outrun some of these quotes. Let’s evaluate the most damning of them.

“Sooner or later, somebody is going to get hurt, and then they are going to blow it all out of proportion … But go back and look at the overall picture. For a guy who is supposed to have run pitchers into the ground, look around and see our track record of how healthy our pitchers have stayed. Who has had healthier pitchers?”

To some, nothing defines Dusty Baker, manager, like Kerry Wood and Mark Prior, pitchers. The season before Baker’s quotes, the Cubs’ top three pitchers were Carlos Zambrano (214 innings, 3.11 ERA), Prior (211, 2.43), and Wood (211, 3.20). They were, respectively, 22, 22, and 26 years old during the 2013 season. Prior and Wood were first-round draft picks, chosen second overall in 2001 and fourth overall in 1995, respectively.

Lacking both rotation depth and a reliable bullpen (Joe Borowski, anyone?), Baker rode his young stars hard. Zambrano averaged 107 pitches in his 32 starts, and had six starts in which he threw 120 or more pitches. Wood averaged 111 pitches in his 32 starts, with 13 of more than 120 pitches, including one of 130, and one—a seven-inning outing in May!—in which he threw 141 pitches. Prior averaged 113 pitches in his 30 starts, with nine of 120 pitches or more, three of them over 130. Additionally, in the postseason Wood made four starts with pitch counts of 124, 117, 109, and 112; Prior made three starts of 133, 116, and 119; Zambrano made three starts of 95, 102, and 112.

Two of the three were never the same. Prior pitched parts of the next three seasons, compiling a 4.27 ERA over 329 innings, before injuries ended his career. Wood lasted another nine seasons but never qualified for the ERA title again, eventually converting to relief in 2007. For the rest of his career, he pitched 477 innings with a 3.77 ERA. Only Zambrano was unimpeded, as he started 30 or more games in each of the next five seasons. While he was only 31 when he threw his last pitch, his demise was perhaps a product of poor control rather than a destroyed arm.

So yes, Baker was arguably complicit in the breakdowns of Wood and Prior. And that was a mistake. But did he display a foolish consistency, continuing to run his pitchers into the ground?

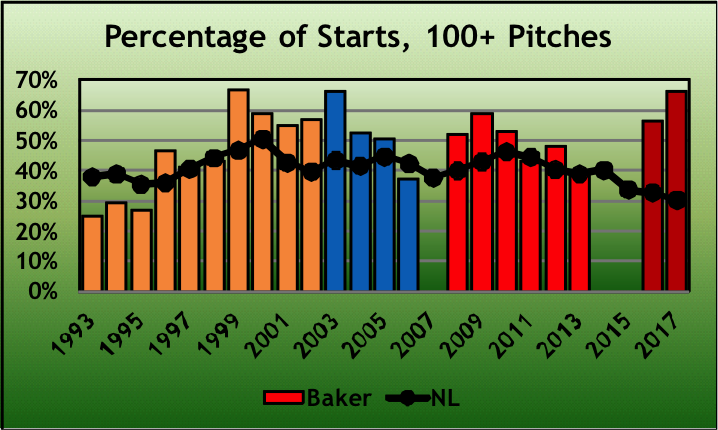

Here’s a chart showing the percentage of pitchers, under Baker, whose starts exceeded 100 pitches. I’ve color-coded the chart: orange for Giants, blue for Cubs, red for Reds, dark red for Nationals. The solid black line indicates the National League average during the years 1993-2017. (Baker didn’t manage in 2007, 2014, or 2015).

So yes, Baker has pretty consistently had his starters throw 100-plus pitches more frequently than average. But there’s a big caveat. Baker has generally managed good teams, with winning records in 14 of his 22 seasons. Good teams usually have good pitchers. Good pitchers are more likely than poor pitchers to last 100-plus pitches. Letting Max Scherzer throw 107 pitches when he’s cruising isn’t foolhardy. Letting Ubaldo Jimenez push his pitch count above 65 when it’s the third inning and he’s already given up nine runs isn’t a viable option.

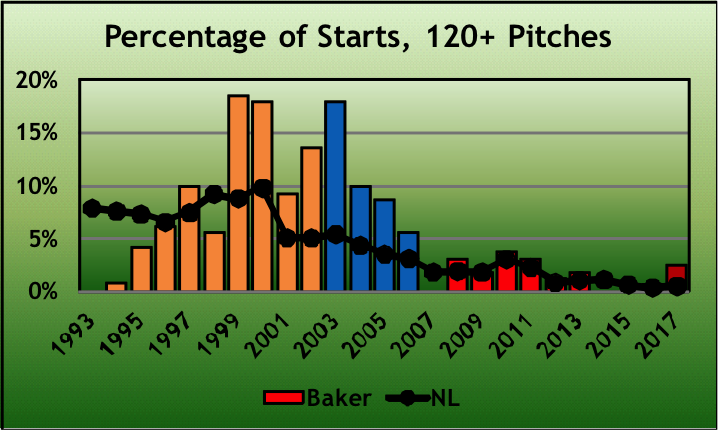

So let’s look just at games in which Baker’s starters threw 120 or more pitches, as the young trio of Zambrano, Wood, and Prior did 28 times in 2003:

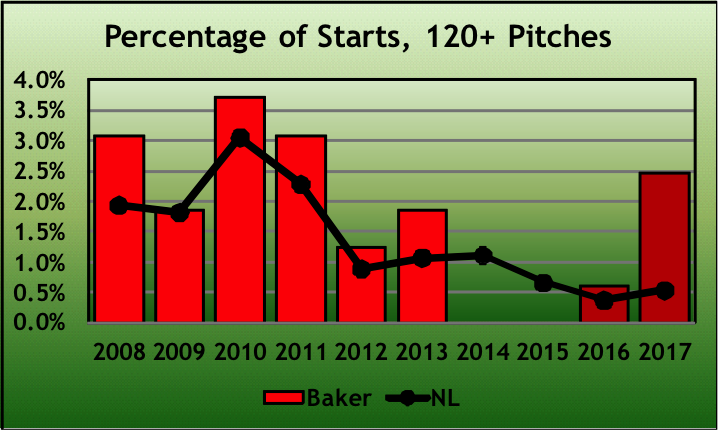

As you can see, Baker started riding his starters hard in 1999, reaching a peak, relative to the National League, in that 2003 campaign. But he learned something during his Cubs tenure, and, like the league as a whole, became reluctant to run up his starters’ pitch counts. Let’s zoom in on his Cincinnati and Washington tenures:

Yes, he’s still above the league average, but we’re talking very small numbers. In 2016, one Nationals starter—Tanner Roark, April 23, 121 pitches in a 2-0 victory over Minnesota—threw 120-plus pitches. That was enough to slightly exceed the NL average. This year, Scherzer (June 21 and July 7), Roark (May 2), and Gio Gonzalez (August 20) had games with pitch counts of 120 or more. At the time of those games, Roark was 30, Gonzalez 31, and Scherzer 32. Baker doesn’t mess with young pitchers’ arms anymore. No foolish consistency.

“I think walks are overrated unless you can run … If you get a walk and put the pitcher in a stretch, that helps. But the guy who walks and can’t run, most of the time they’re clogging up the bases for somebody who can run.”

While the usage of Prior and Wood was probably the biggest knock against Baker, the above quote gets the most ridicule. Walks are good! They contribute to offense! Given the choice of clogged or unclogged bases, always go for clogged!

Yet, you have to admit, there’s a truth there, if one that’s not well-stated. Little League coaches’ admonitions aside, a walk isn’t as good as a hit. If there’s a runner in scoring position and first base is open, a walk isn’t going to advance him. We already know that. Bill James’ original Runs Created formula gives walks the same weight as hits in its “On Base” component, but gives walks a weight of only 0.26 compared to singles in its “Bases Advanced” component.

And once a batter’s on base, his speed does come into play. This season when Byron Buxton was on first or second when a batter hit a single, or on first when a batter hit a double, he took an extra base 71 percent of the time. He had an on-base percentage of .314. That’s the same on base percentage as Mike Moustakas, but Moose took an extra base only 13 percent of the time—he went first-to-third on a single only once in 19 chances and never scored the 13 times he was on first when a double was hit. So Baker has a point: Moustakas’s .314 OBP didn’t contribute as much to Kansas City’s offense as Buxton’s .314 contributed to Minnesota’s.

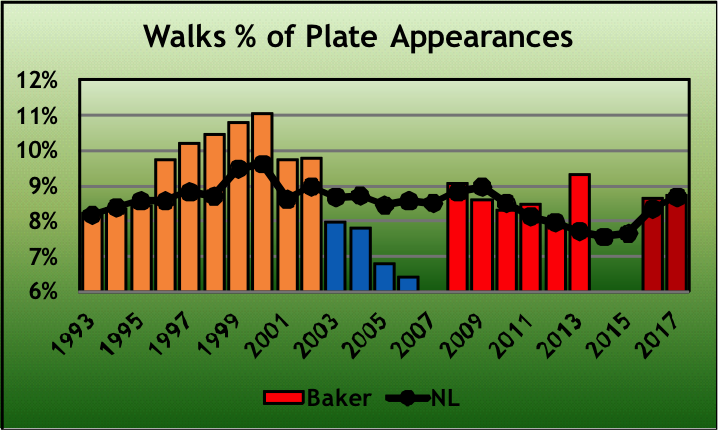

But did Baker’s teams actually eschew walks, emphasizing aggression at the plate over patience? No, they did not:

While he was in San Francisco, NL hitters walked in 8.8 percent of plate appearances. Giants batters did so in 9.7 percent. In Cincinnati, Reds batters had an 8.6 percent walk rate compared to 8.4 percent for the league as a whole. In Washington, the team walk rate was 8.7 percent vs. 8.5 percent for the league. Only in Chicago—where he managed free-swingers like Aramis Ramirez, Corey Patterson, Michael Barrett, Ronny Cedeno, and Neifi Perez—did his teams walk at a below-average rate.

So the complaints about Baker? They’re not really fair. He doesn’t have his batters avoid walks, at least to any extreme degree, and while he rode young pitchers hard a decade-and-a-half ago, he learned his lesson, avoiding a foolish consistency.

Baker seems to be a good manager of people. Players enjoy working for him. He may not be the very model of a modern sabermetric general, but he’s not the dinosaur he’s made out to be, either. Certainly, he has his faults, as do we all. But a little mind doesn’t appear to be one of them.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Forgive us, then, for remembering that Dusty The Arm Killer put Prior back into a game just moments after he landed on his shoulder following a collision with Marcus Giles on July 11, 2003.

Prior grabbed his shoulder after the tackle and stayed on the ground for a couple minutes, but good thing Baker only pitched him 2 2/3 more innings that day.

Immediately following that extra 66 pitches - during which he gave up 4 runs on 5 hits and 2 walks - Prior missed a month with a shoulder injury.