Like so many Japanese men of his generation, Shingo Furuya was a company man. Fresh out of college with an economics degree, he joined the Hanshin Electric Railway Company and devoted his life to it: worked ridiculous hours, floated through reorganizations and sideways promotions. It’s how he became the manager of one of Hanshin’s corporate subsidiaries: the Koshien baseball stadium. At 56, after one more business dinner, he became the general manager of the Hanshin Tigers.

At first blush, it seems like a strange progression. Furuya didn’t know baseball; Japanese general managers rarely did in his time, 1988. The field manager was responsible for the team roster, and the owners for the financial decisions. Furuya’s position was mediator, negotiating with both sides, and with the players themselves, trying to keep everyone happy. It was not, at that moment, an easy job. Champions a few years earlier, the Tigers had slipped into last place. Their hometown hero, Masayuki Kakefu, was seeing his glorious career wind down early as he struggled with injuries. He’d made public his intentions to retire; Furuya was busy trying to talk him out of it. And then there was Randy Bass.

Japanese teams had long struggled with their gaijin players in the seventies and eighties; the allure of talent always seemed to be undone by underperformance, miscommunication, alienation, and expectations. Bass, a busted first base prospect in the majors, proved different. He became the league’s MVP and its finest foreign player to date, and was equally on good terms with Japan and his employers. They, in turn, loved him back.

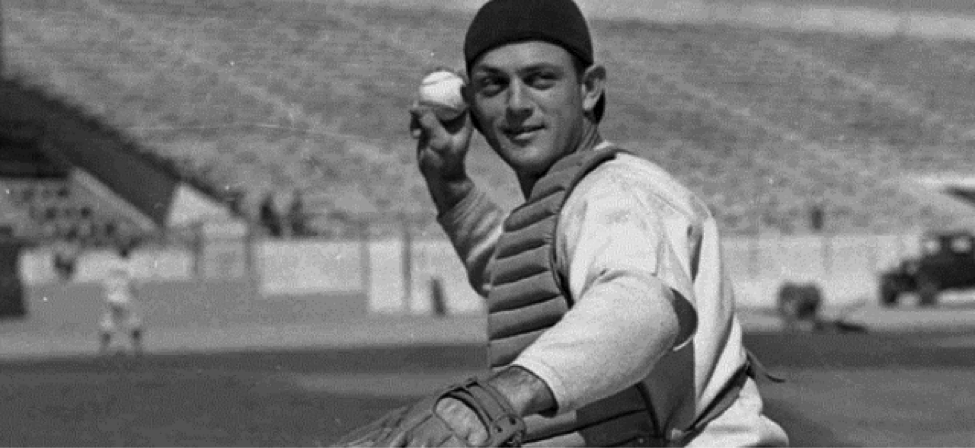

Randy Bass, future king in a foreign land. Photo: MiLB.

But even that happy story couldn’t last. In early 1988, Bass learned that his young son back home, Zachary, needed treatments for brain cancer. Bass asked for, and received, two weeks leave to be there for the treatment, a laudable corporate act by Western standards, shockingly generous by Eastern ones. When the two weeks were up, Bass did not return. There were complications, attorneys, a conspicuous losing streak. The Tigers ultimately responded by cutting their star and waiving their responsibility to pay for medical bills as per his contract.

Bass claimed that he had been given permission by phone to continue to stay by his son’s side. The team declared it a lie. Bass produced an audio recording of the conversation. The man on the other end of the telephone was Shingo Furuya. He knew Bass well, had met his family. He made a promise he had no power to keep. It was true of all his promises.

Furuya traveled to Tokyo to meet with the Hanshin owners in the aftermath. He called his wife that evening, after the stories broke, as he always did when he was on the road. Instead of “sleep well,” he said “goodbye.” Then he stepped onto the external stairwell of his hotel room, eight stories up. Two-and-a-half seconds later, Shingo Furuya died in the garden below.

***

It’s almost difficult to believe in baseball ever being worth taking one’s own life. And in a casual glance, the connection between baseball and self-harm is a fleeting one, punctuated by the psychotic rage of Marty Bergen, the acute despondency of Willard Hershberger, or the alcohol-soaked despair of Hideki Irabu. There are conditions within the game, a self-selection process, which would appear to build some mild immunity to the urge toward self-harm: the dogmatic, myopic positivity of the modern athlete, and the dilution of failure across an endless stream of games.

Williard Hershberger, retrieved from Alchetron, via CC3.0.

There are exceptions like Hershberger, players who were directly rebuffed by their failures, and killed themselves out of despair. Generally, they are pitchers with arm problems, men whose loss of purpose was both abrupt and tangible. Reds starter Benny Frey, in 1937, was sent to the minors after his arm gave out, and he refused the assignment. When his arm failed to heal, he connected a hose from the exhaust pipe to the backseat of his car in his sister’s garage. Pea Ridge Day, after spending tens of thousands of 1933 dollars at the Mayo clinic to revive his own career, slit his throat with a hunting knife.

But even in these extreme cases, there are other factors. The philosopher-poet Jennifer Michael Hecht, in a work to be discussed in detail below, notes:

“In the Great Depression of the 1930s many individuals took their lives, either when they lost all their money in the stock market crash or during the period afterward, with its grinding unemployment. When we think of it now it seems surprising that people could take these widespread hardships so personally, but this seems to be how the mind works–all misfortune feels local.”

So it was with Furuya, who shared the same problems as many middle managers in similar situations. He also shared many of their fates.

***

I spent my early twenties as a lost undergraduate student, failing my useless liberal arts classes and my parents. I missed classes and then grew too anxious to attend classes, anxious that I would be confronted over my truancy. After being put on academic probation, I toyed with the notion of suicide, though never seriously. My lack of ambition proved both my demon and my angel. Lying in bed in the empty midmorning, I envisioned joining the military and throwing my body against imaginary Cossacks. Instead, I sent myself into exile for a time, taught overseas, and the darkness slowly passed.

Recently I finished reading Stay, the philosophical history of suicide and its pros and cons, written by Jennifer Michael Hecht. (Doubt, a similar treatise on skepticism through the ages, is one of my favorite books.) I was surprised to discover it weighing me down, despite the fact that its message is intended to perform the opposite. The thesis is strongly anti-suicide without resorting to the usual tactics of organized religion, shame, and hellfire. It is meant to be positive and constructive.

If you were to ask me directly if I were for or against suicide, as a liberty, I would probably say for. I do not mean dying with dignity in the hands of an incurable and painful illness, and neither does Hecht; that is a separate matter. But for the person who is in anguish, who seeks control over his or her own existence and identity, who simply does not want to live: instinctually, I would allow them the choice not to.

Hecht (and others, as she details in her history) do not. The counterpoint: Because it is a lonely act, it is by nature a selfish one, not because it necessarily willfully ignores or betrays the feelings of others, but because the signal between them is severed. She does make the argument, for completeness, that suicide is a crime against the future self because its desire may only be passing and its results permanent; the fact that some people who make the attempt come to regret doing so seems proof enough. Ernie Lombardi is an example of this. But to Hecht, the primary drive toward taking one’s own life is alienation.

What makes suicide wrong, she argues, is that we owe our lives to the people around us, those who love us and depend on us. We owe it to our society, the shared strength of which is diminished by our decision to opt out. When it comes to existence, we are not allowed to vote with our feet; our decisions touch others no matter how isolated we feel (or want to be). We cannot remove ourselves from the world.

I sympathize with this sentiment, and yet as I slowly took it in, it chafed at me. The timing, personally, is poor. I currently possess two children, ages three and one, who are convinced they will disappear if I am not looking at them. The yoke is heavy enough. And as far as the social contract, it’s perhaps not the best time to argue for the indebtedness of the individual to the government, at a time when the latter is in the business of consolidating power. If we live to serve a society, it’d be nice to see that society hold up its side of the bargain a little better.

But I understand that these are means to an end. Society has for nearly two millennia sought ways to dissuade suicide: rendering it illegal, sinful, shameful. Bodies of the voluntarily departed were publicly defaced, inheritances denied, barred from heaven, all in an effort to make the act as unappealing as possible for the survivors. And for good reason: sociologists in the 20th century discovered that suicide does, in fact, have a snowballing effect in society, either through popular culture (The Sorrows of Young Werther set off an epidemic upon publishing) or by an infectious despair at the loss of a friend or relative. Hershberger in particular was surrounded by suicide his entire life. It was a constant reality to him.

Ianthe Brautigan, daughter of the counterculture author Richard Brautigan, explains in the preface to her own memoir, a work entirely about her relationship to her father:

“This is not a book about therapy, nor is it a self-help tome about suicide and grief. I threw away all my books on both subjects long ago … Although I don’t have any answers, I firmly believe there is no right or wrong way to navigate the suicide of a loved one, except to make sure you do. I don’t pretend to be put back to rights. I just wanted to help break the silence that exists concerning suicide, so I broke mine.”

***

People outside of Baltimore might not remember Mike Flanagan. He won the AL Cy Young award for the pennant-winning Orioles of 1979, and made the All-Star team the following year, but after that he was a quiet and constant presence in the middle of Baltimore’s rotation for a decade. He threw the final home pitch at Memorial Stadium in 1991, by then a middle reliever, facing two Tigers and striking them both out. After retirement he stayed with the team, moved up to vice president during the franchise’s lean years in the late 90s, when the Yankees dominated all. The losing built up, and Flanagan found himself relocated to the broadcast booth, doing color for MASN.

Mike Flanagan and Earl Weaver, 1979. Photo from AP.

Flanagan was a quiet, thoughtful man, constantly reflective, always trying to find something to tweak or improve. He was the quintessential crafty lefty, employing study and technique in place of raw talent. He took that same work ethic into the front office, where he toiled to improve the club despite little positive results. In public, he was polite, non-confrontational, amiable, and silent. In private, the frustrations of every loss, every setback boiled within him.

“He used to talk about shadows," his wife Alex told reporter Dan Rodricks in 2012. "He would say, 'Sometimes there's this shadow that comes into my life,' and he wouldn't see anything good, just these shadows. … He would see the world in black and white, without color."

Stung by criticism in the press and online, struggling to make ends meet with inconsistent work, unable to find value in himself, Flanagan began to drink: at first, openly, and then after a heart-to-heart with Alex, in secret. He took a shotgun and shot at woodchucks on the property as therapy. When Alex traveled to be with her ailing mother, one day, Flanagan turned the weapon on himself.

Alex commented that she still felt guilt, still searched for other pathways that might have led out of the darkness. It’s natural, and tragic. The family knew, they supported, cajoled and cared. They searched for a way to connect, to show him how valuable he was. They couldn’t reach him.

***

At the end of his book, The Conquest of Happiness, the philosopher Bertrand Russell caps off 200 pages of what makes people unhappy, and finds in conclusion:

“The whole antithesis between self and the rest of the world, which is implied in the doctrine of self-denial, disappears as soon as we have any genuine interest in persons or things outside ourselves. Through such interests a man comes to feel himself part of the stream of life.”

Though he lived to a ripe 99 years old, Russell grew up in the Victorian era of Britain, a time when appearances and repression dominated culture. He rejected these things and, late in life, threw himself into the noisy, active, living democracies of the American 1960s. Going with the flow didn’t mean avoiding conflict, or not making waves: it meant immersing one’s self in the current of the times, to feel a part of something. To avoid feeling alone.

As an introvert, I don’t find the prospect particularly thrilling. I find it difficult to reconcile my own preference for personal, local democracy and my desire, at all times, to be left alone in my room with a nice book. But in terms of living, the grand search for meaning, it’s indisputable: the key is to immerse. To live in whatever way you choose, as long as it’s not in silence.

And that brings us back, finally, to baseball. Sometimes I joke that I got into baseball to have a way to avoid talking about real things to strangers. But at the same time, there’s something real in this. In a social network that feels increasingly isolated, baseball offers an increasingly rare opportunity to feel connected with other people, a model for taking disparate individuals and creating a working team. It is instant camaraderie.

A baseball team is, among its other properties, an excellent microcosm for a small society: specialized people banding together to achieve a common goal, dependent on each other’s skills, stuck with each other’s personalities. Thomas More would be proud. As with every collective, there are problems, differences in direction and ability, inequality and unfairness. Regardless, each is its own nation. Any member leaving the arrangement would have an obvious effect on the welfare of the whole. Any member being left behind loses a piece of themselves.

Ballplayers do still harbor their private problems, hide injuries from their trainers, grouse about management in hallways, suffer anxiety and depression despite a fan base that expects nothing less than 100 percent performance, even the day a man’s child is born. Similarly, we should strive to destroy these barriers, allow the life of a ballplayer to be as natural as we would want our own. We should strive for openness, for understanding, just as we would a suffering friend. We should all make a baseball team with our baseball teams.

***

When they ran tests on the brain of Ryan Freel, former utility man for the Reds, they found evidence of second-stage CTE, the first such discovery in a baseball player. Long known to be an issue with football players, its discovery within a player in a relatively low-impact sport renewed awareness that brain trauma was, in fact, a problem in professional sports. Freel himself once estimated he suffered “nine or ten” concussions. An outfield collision that sent him off the field in a stretcher derailed his career, and a pickoff throw that tore off his helmet effectively ended it.

Ryan Freel. Photo: Getty Images.

Freel made a comeback attempt, did some youth coaching, but as with Flanagan he found stability a difficult thing to maintain. He, too, struggled with alcohol, though he seemed to have bested it. When the tests confirmed to his family his erratic behavior, the mood swings and headaches and attention span problems, it was in one way a relief.

"Oh yes [it's helpful], especially for the girls," Freel's mother, Norma Vargas, said of his three children, speaking of the study to the San Diego Times-Union. "We adults can understand a little better. It's a closure for the girls who loved their dad so much, and they knew how much their dad loved them. It could help them understand why he did what he did. Maybe not now, but one day they will."

Freel’s stepfather saw the other side of the coin. “It's a release in that there was a physical reason for what he did," Clark Vargas was quoted. "On the other side, for me, Ryan fell through the cracks." Whether by medical ignorance or indifference, baseball, in a way, had failed one of its own.

***

In Roman times and before, suicide was generally considered at least neutral and potentially noble: Socrates drinking the hemlock, Samson pulling down the temple. It transformed, over the centuries, along with other mental illness into something secret, shameful, something to disguise. We are only now beginning to understand how deadly that private shame has been. Men like Hershberger, Flanagan, and Freel ended up alone, in pain, amongst their friends and family. It may not always be possible to solve the divide—depression is as deep as it is obfuscated—but reversing the stigma of self-pain is the best way forward.

Socrates, refusing to appeal his suspension.

Baseball did not save Shingo Furuya; in fact, the entire structure of his existence, the powerlessness and the responsibility, the societal norms concerning corporate honor and expectations, appear to have driven him to his act. I wish it had been otherwise. Japan has struggled to overcome its culture of suicide, which appeared to be improving until the economic downturn of the late 90s drove it up again.

Furuya’s fate was sealed as he stepped out of the owner’s meeting that evening, because at that point, there was only one path left that he could see. If he had been honest with his wife, if he had called Bass, if he could have rejected the code of honor baked into his sensibilities, there may have been another way. There is almost always another way, when one is rational. It is difficult to be rational, when the shadows appear.

In the end, I guess my issue with Stay is not its message but the restrictions of its historical perspective, naturally oriented on the decision, and liberty, of the individual: the idea that eliminating suicide and failure is their responsibility or service toward society, rather than the other way around. In my mind, preventing alienation is the job of the community, not the individual, and suicide is a symptom of the failure of a society to tend to the health of its citizens.

Even those philosophers who fight for the sake of liberty in suicide aren’t rooting for it; no one wants people to die. The ideal outcome is for everyone to have that choice, and choose to reject that outcome, to find their value in living. That is the difficult thing, the important thing. But in the face of shadows, expecting rationality and utilitarian calculus out of those suffering feels lofty, dispassionate. Instead of rejecting death, we should be defending life.

Fortunately, we have tools for this, for creating a sense of value and community in existence. There are so many to choose from: we have art, we have philosophy and religion, we have charity, and we have baseball.

One clear virtue in baseball: that if suicidal behavior is contagious, the opposite is equally true. As models for the human struggle, athletes who were able to break through their silence and share their stories can create a positive culture. Men like R.A. Dickey, Evan Gattis, and Aubrey Huff (among others) have come forward to talk about their own battles against depression, doing their part to open cultural dialogue on the subject in the face of the stereotype of the athlete as infallible and monomaniacal.

It’s easy and cynical to treat baseball as a sort of postmodern nationalism, to see in it the usual gerrymandering and division of people by geography and demographics. But it also combines. It gives us a reason to talk to and care about each other, to share experience, create memories. As much as the language of baseball shouldn’t replace actual language, there is something in it, a code by which we can all relate to the people next to us, to feel part of something. Even if it’s a placeholder for more meaningful conversation, for an avenue toward help, it’s still better than silence. Anything is better than silence.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now