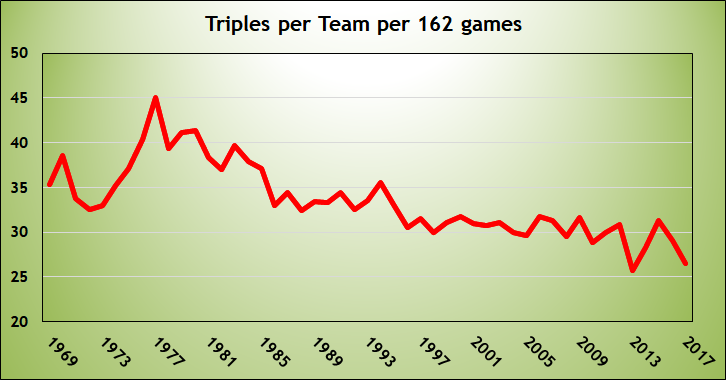

When I wrote about some under-the-radar trends in the 2017 season, I missed one: Triples. Triples are way down during 21st century baseball in general, and the current decade in particular. (Throughout this article, I’m going to look at the divisional play era, 1969 to the present.)

By this measure, the five seasons in baseball history with the fewest triples are, in order: 2013, 2017, 2014, 2010, and 2016. We’re in a triples drought.

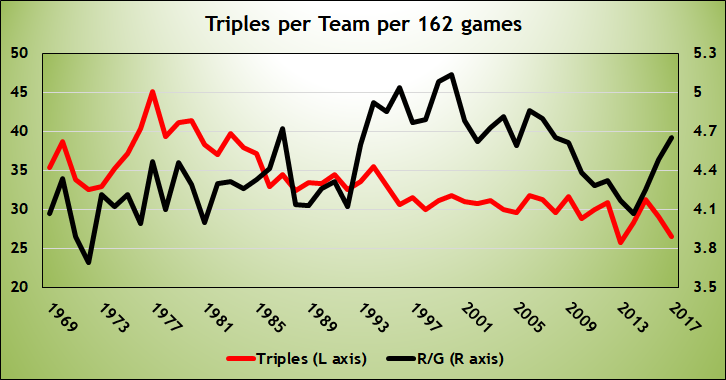

This struck me as curious. This isn’t just a reaction to the scoring environment. Here’s the same graph, but the black line is runs per team per game.

It makes sense that, in a high-scoring environment, there’s less reason to stretch a double to a triple, because the batter behind you has a good chance of driving you in whether you’re at second base or third base. Statistically, that means the correlation between triples and scoring would be strongly negative: More scoring results in fewer triples. But that’s not what’s going on here. The correlation between triples and runs per game is -0.30. It’s negative, but barely. It’s not a strong relationship.

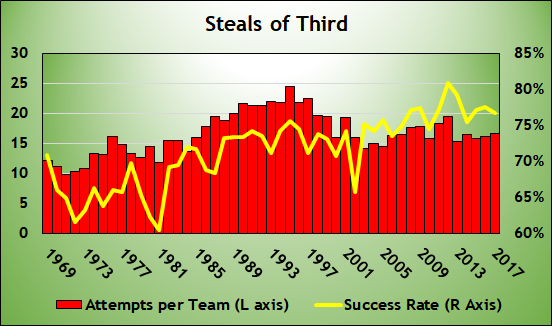

This got me thinking: How widespread is the aversion to advancing from second base to third base? Here’s a graph illustrating steals of third.

There are a couple things going on here. First, baserunners are increasingly successful when they try to steal third. The years with the highest success rates on steals of third are, in order: 2012, 2013, 2016, 2009, and 2011. This past season ranks eighth. Excluding the strike-shortened 1995 season, the 13 years with the highest rate of successful steals of third base are all since 2002.

But that success hasn’t been accompanied by more attempted steals. Teams have attempted 15-17 steals of third base per 162 games in each of the last five seasons. They averaged 18 or more every year from 1986 to 1999. They’re more successful when they try, but they’re trying fewer.

One other way a runner can sprint from second to third is by going first-to-third on a single. The analysis there is a little tricky. On May 9, Billy Hamilton was on first with one out when Zack Cozart singled. Hamilton stopped at second. That’s partly because Cozart’s hit was a line drive to left field, but Hamilton is really fast. It’s mostly because Devin Mesoraco was on second ahead of Hamilton. Mesoraco hasn’t scored from second on a single since 2014. He wasn’t going to score that evening in Cincinnati, either. Hamilton held up at second because Mesoraco was at third.

I looked at singles hit when the runner on first was the only baserunner or when the only other baserunner was at third. That allowed me to filter out situations in which a runner at second might’ve prevented the runner on first from advancing beyond second base.

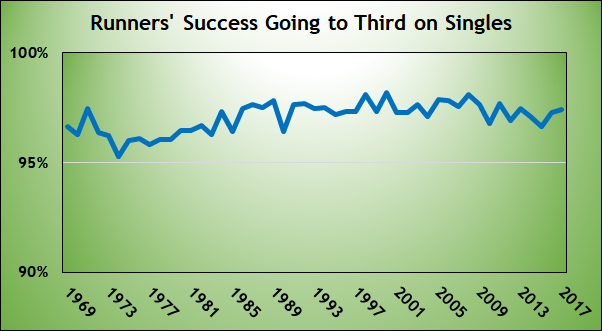

First, let’s look at how often runners trying to go first-to-third on singles succeeded.

For those of you who don’t like the way I play around with the y axis on my graphs: Cool down. I’m not trying to pull anything here. What this graph shows is that the success rate when runners try to go from first-to-third on singles has been pretty constant for nearly half a century. It’s stayed within a narrow band between 95.3 percent and 98.2 percent. No big change.

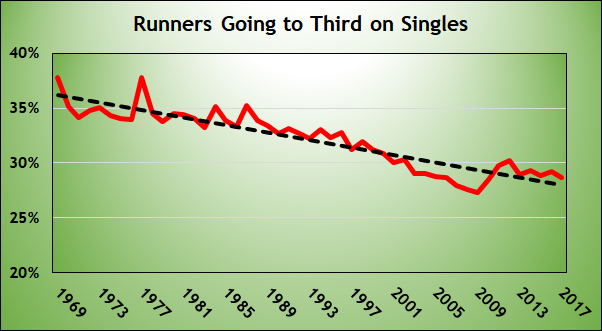

What is a big change, though, is baserunners’ willingness to attempt to advance. This graph shows the percentage of baserunners on first, with either no other runners on base or another runner on third, who’ve attempted to advance to third on a single.

The black dashed line is a trendline, but you didn’t really need it, did you? The trend is pretty obvious. Runners have become more reluctant to try to advance to third on a single, even though their success rate has remained unchanged.

So let’s put these three components together:

- Batters are less willing to try to stretch a double to a triple.

- Runners are less willing to try to steal third.

- Runners are less willing to try to advance from first-to-third on a single.

It’s as if there’s a stop sign at second base. But why?

We can dispense with some possibilities pretty easily. It’s not because baserunners are slower. Athleticism, across all sports, has improved with advances in training, nutrition, and lifestyle. That athleticism has also resulted in stronger throwing arms for catchers (on stolen base attempts) and outfielders (on runners trying to take an extra base), but with faster runners, that’s got to be sort of a draw, right?

Similarly, this doesn’t seem to be driven by the scoring environment. As noted above, it doesn’t make sense to try to eke out an extra base when there’s a reasonable chance that the next guy at the plate is going to put one into the seats. But the decline in aggressiveness on the basepaths began in the low-offense 1980s, continued through the Steroid Era, was unabated when scoring tumbled to a 4.1 runs per game nadir in 2014, and has endured in the current record home run environment.

Part of the answer, I think, is analytics. Run expectancy tables consider every base-out state (bases empty, runner on first, first and second, etc., with zero, one, or two outs) and count the average number of runs scored in that situation. This isn’t statistical hocus-pocus; it’s a snapshot of what actually occurred during a season. In 2017, there were 34,180 occasions when a batter came to the plate with no outs and a runner on first. The batter’s team scored 30,574 runs in those innings. So the average team in 2017 with a runner on first and one out could expect to score 30,574 / 34,180 = 0.8945 runs.

Say you’re a runner at first base with nobody out when a single is hit. We can use run expectancies to see that, in 2017, if the runner stops at second, his team could expect to score 1.4810 runs. If he makes it to third, the run expectancy rises to 1.7333, an increase of 0.2523 runs. However, if he’s thrown out and the batter holds, there’s a runner on first with one out and the run expectancy drops to 0.5407, a decrease of 0.9403 runs. So the runner had better be 0.9403 / (0.9403 + 0.2523) = 79 percent sure that he’ll make it, or he’s going to cost his team runs.

Similarly, a runner on second with one out represented 0.6899 runs in 2017. If that runner goes to third, either by stealing the base or stretching a double to a triple, the run expectancy is 0.9325 runs, an increase of 0.2426 runs. If he’s thrown out, though, his team has nobody on and two outs, and the run expectancy drops to 0.1094, a decline of 0.5805 runs. So stealing third, or trying to stretch a double to a triple, with one out had better work 0.5805 / (0.5805 + 0.2426) = 71 percent of the time, or the team is leaving runs at the table. Scroll back up to the chart of third base stolen base success rates, and you’ll see teams giving away runs throughout the 60s and 70s.

So sabermetrics has resulted in players putting on the brakes. But that doesn’t explain everything. After all, baserunners are doing a lot better than the break-evens that run expectancy suggest. What else is driving the caution?

I’d argue it’s another sabermetric concept: The replacement player. Specifically, an all-out sprint, even for 90 feet, risks injury. A player could pull a hamstring. He could get hurt sliding. He could injure himself landing on the base. His replacement is likely to be, well, replacement level. If you lose Mike Trout to a thumb injury, it’s going to cost your team a lot more runs than the 0.2426 gained in the paragraph before last. So my guess—and it’s just a guess, feel free to shoot it down in the comments section—is that managers and coaches are reluctant to try to take a extra base in a non-critical game situation for fear of injury. Maybe it’s not conscious, but it’s there.

Taken together, barring a significant change in the game, it seems unlikely that we’ll see players scampering over to third base the way they did a few decades ago.

Thanks to Rob McQuown for copious research assistance

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

I know these are extreme examples, but if speed is less valued today by organizations, it would not surprise me that the players they choose to employ are not as fast. I'm pretty confident that if the 1987 St. Louis Cardinals were to be transported in time to 2017 and challenge the 2017 Cardinals to the 50-yard dash, I am guessing most of the top finishers are going to be from 1987.

I am not confident that MLB players are slower today, but it certainly is possible.

That being said, I suppose that in the artificial turf-dominated '80s, you may have a point. The Yankees fell in love with speed and signed Dave Collins, the Rapid City Rabbit, to a free agent contract before the 1982 season. (They fell out of love and traded him at the end of the year.) But I don't know if you could still make that case in the 1970s as well.