The bible verse on Rafael Palmeiro’s Twitter profile reads:

“But he said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.’ Therefore I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me. That is why, for Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong.”

After that, another word: Faith.

Being a professional athlete—hell, being a functioning adult—requires some level of faith. Faith in one’s self, the indefatigable athlete’s optimism that crowds out the possibility of failure; or, in times of failure, faith in the law of averages. We have faith as we cross the street that the cars will obey the little red light and not end us, wipe out our lives and our loves in a single moment. Faith is both a virtue and a tragic flaw, depending on how the story ends.

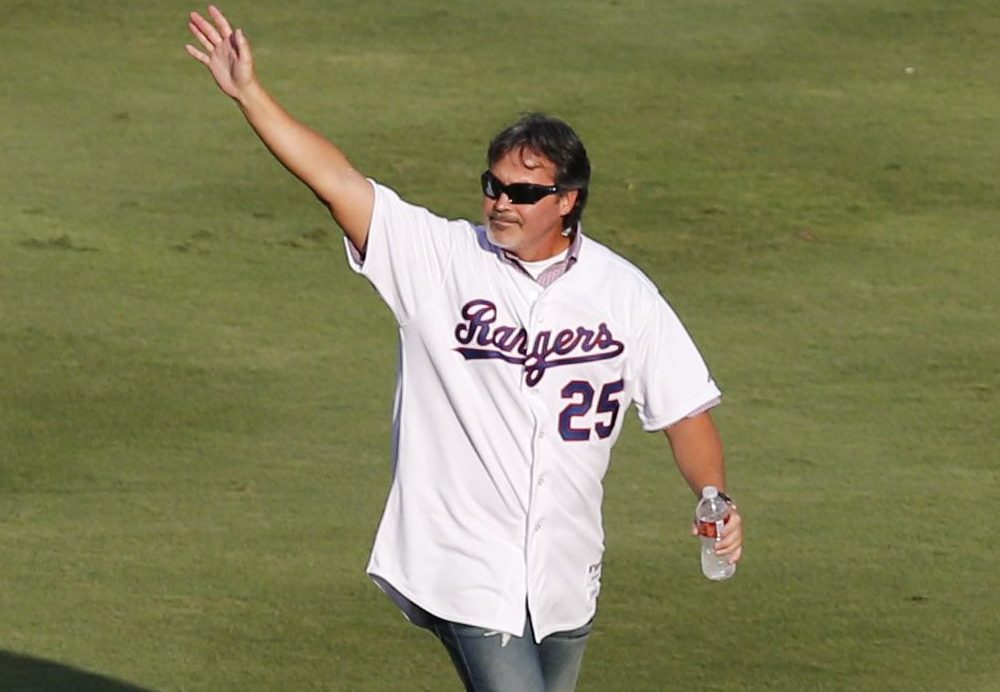

Faith is Rafael Palmeiro, 53 years old, so small and pixelated he almost appears to be his own video game character, hidden in white cotton clothing as he takes batting practice. It’s a strange 45 seconds of film: the empty batting cage feels a little oppressive, like the hold of a ship. Palmeiro swings as if underwater, almost gently, a swing so impossibly slow that when he connects, and the ball flies away toward an invisible right field, time itself seems to crawl.

Faith is Palmeiro discussing his comeback with reporters last month, dismissing the prospect of riding buses with teenagers: “If I go to spring training with a legitimate chance to make the team, I won’t have to go to the minors,” he said. A citation, here, is needed. But his motivation is not complicated. Bud Selig already has his place in the Hall of Fame, and Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens appear not far behind. Palmeiro is searching, either by narrative or technicality, for a chance to prove he belongs with them, that he can still change his story.

Clearly, this is madness. Every spring is sprinkled with comebacks, fertilizing the fields of February, to mixed results. One year it will be Brad Penny, a rumor created to generate rumors, meme fodder. Or an enigmatic Tim Lincecum. Or a rejuvenated Colby Lewis, or Jose Rijo, bringing his Hall of Fame vote with him to the mound. Or there’s Ed Vosburg, a chapter unto himself: a major leaguer at 24, again at 28, out of baseball at 32, injured at 38, and a major leaguer again at 45, exile and champion. These stories self-perpetuate, they embolden. All required that same faith, the ability to shut out the people who called it madness.

But no one has ever done what Palmeiro plans to do, plans as casually as one of his swings in the cage. Julio Franco retired from the Mexican Leagues at 50, having spent his 40s playing and training regularly. Jim Palmer, at 46 and seven years departed from his final start, already in the Hall of Fame, lasted two innings of spring ball before conceding. This isn’t the dream of a pitcher whose arm no longer seems to throb, or the first baseman toying with a knuckleball. This is a man attempting to do the exact thing he had done a decade-and-a-half before, when he was no longer capable of the task, willing this time to be different.

***

Nearly three decades ago, when Palmeiro was still a rising star, other men went through what he goes through now. Colorado real estate developer Jim Morley decided to create his own baseball league, choosing to counter-program by placing it in sunny, then-baseball-devoid Florida in the winter months, stocking it with an untapped resource: retired major leaguers. The Senior League ran for a season-and-a-half before dissolving, and it proved to be a fascinating and flawed idea. Morley hoped that the aged Florida citizens, many of them retired transplants or tourists, would flock to see their old favorite players wrestle for one more chance at glory.

The league had some names: Fergie Jenkins, Rollie Fingers, Bill Madlock, Graig Nettles. But what they quickly learned, what Palmeiro has yet to discover, was that as baseball entered the event horizon of retirement age, youth easily trumped talent. One of the top players in the league was the famous Tim Ireland, with his eight major-league plate appearances. By being 36, just over the minimum age cap, Ireland’s youth gave him a huge advantage, one that only grew as the season went on and hamstrings league-wide began to fray. Statistics for the senior league are hard to come by, but Ireland finished the year batting .374, with a .434 on-base percentage.

The league and its players developed a reaction similar to the one Palmeiro is now receiving: curiosity, amusement, but mostly discomfort at watching men who can’t let go. In his book, Extra Innings, David Whitford sits down with Bob Stoddard, a middle reliever in the 80s who knew, unlike most of the others, that this was no audition for a spring invite, and that at 36 his major-league career was likely over. Asked why he kept playing, he answered:

“You accept the fact that you’re not what you were when you were twenty-two. I know that I’m not gonna be as good as I once was. I know I can’t throw the ball ninety-five miles an hour anymore. But I know I sure know how to pitch, and I know these guys know how to hit. I’m not going out there thinking it’s a joke. Every day I pitch, even now, I learn more about the game.”

What we find isn’t a man trapped in his own youth, clinging to his fabled status as Major League Baseball player. Stoddard is doing the opposite: aging, growing, learning at the thing he did better than anything else in his life. It’s admirable, it’s harmless, and yet to most of us, it’s so clearly sad.

***

The news of Palmeiro’s comeback has been met with universal scorn: scorn for the man who used steroids and lied to congress, scorn for the sad old man fouling off pitches in a batting cage, and dreaming like a boy. It’s a democratic scorn, a common hatred for the person who earns undeserved attention, who isn’t content with his fame and his millions. We are a paradoxical culture, brandishing an ethos of dreaming and climbing, yet tearing down those who consider themselves special, and fail to know their place. For the former star, it’s just another element of his own narrative, the weakness and doubt he must overcome.

Few things in baseball draw ire so efficiently as the ballplayer who refuses to walk away, and instead tarnishes his own legacy and our memories, like the blurring Ken Griffey Jr. sleeping in the clubhouse. It’s strange that we’ve decided to speak on behalf of the players in this respect, particularly in the modern game, with its focus the allocation of human resources. The modern ballplayer is simply asked to execute in the situation he is provided. If Palmeiro truly is terrible, baseball’s invisible hand will brush him aside; certainly no team will be interested in adding him for his clubhouse presence alone. Reality will smother Palmeiro without our help.

But if we take that away, what’s left? A man who wishes he were a Major League Baseball player, just like the rest of us, but unafraid. That, more than anything else, is his true crime.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now