Derek Jeter does not like the donger machine. I have a suggestion for Derek Jeter. Derek Jeter can eat a six-foot bucket of—no? I’m being told no.

Here’s what you do, since you want to be rid of it so bad. You put the thing on the bed of a large truck. Military-size truck, probably, honestly. Pit-mine-machinery-size struck. And in any event once you get that thing on a truck, you’ve got yourself Miami’s hottest new mobile food destination. You pull that bad boy up outside the club. You pull it up at the brewery. You pull it up at the bar. Really, you just pull it up anywhere there is both alcohol and a willingness to actually have fun, which is to say you pull it up anywhere Derek Jeter is not.

It’s seven stories tall, so we don’t even need to worry about what kind of food truck it’s going to be. It’s all kinds of food trucks. It’s every food truck. It’s a ceviche & Panamanian-Chinese fusion & overloaded cheeseburgers & traditional taco & PB&J-but-grilled & Vietnamese comfort & tiki & empanadas & Korean-Mexican & soft serve & fried chicken & beignets & coffee & pizza & breakfast sandwiches & sushi burrito & lobster roll & migas & cheesesteaks food truck. There’s room for all these things. It will be a mobile Food Hall, a mobile Clifton’s Cafeteria. No hot dogs, though. Too painful. Too many memories.

And and and here’s the big thing, right, because the point of the donger machine isn’t that it’s a donger sculpture, but that it’s a donger machine, i.e. it has moving parts and it does fancy stuff when a donger happens. But we don’t have dongers in real life, not most of us, anyway, so the machine aspects are going to have to get repurposed. So here, obviously, is what you do, which is you designate one menu item per day as the Donger Machine Secret Item of the Day and every time that item is ordered WOOWOOWOOOWWHOAAAA the donger machine lights the hell up and the dolphins or swordfish or whatever those are go jumping and the seagull swoops around and the geyser spouts off and just all holy hell breaks loose for like a solid 30 seconds. Because when someone orders the Tofurkey Tornado Tacos at Donger Truck, my friends, my gosh, we all deserve a show.

There’s an old wives’ tale

That the hair and the toenails of a person

Keep growing after death.

It’s not true, of course. I like the idea

Of the body, ripped free of its spirit

Still grasping at something,

Stretching outward with the last dying embers.

Like everything, it’s an illusion

The skin retreating, keratin left behind.

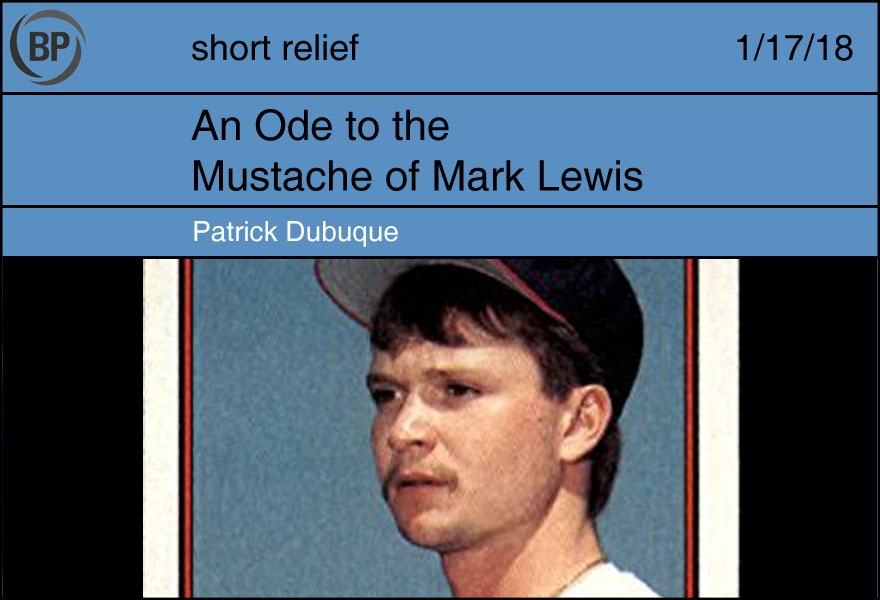

Was it the same for your mustache, Mark Lewis?

You, a child in men’s children’s clothing

Your accomplishments celebrated

Before you had time to accomplish them.

You, who began your career a thousand hits in the hole.

You, with a visage so cherubic

It made Wally Joyner look like a drunken longshoreman.

Was it a disguise? A motivational tool?

Or was your face already beginning to disappear?

That shadow over your upper lip

Entered my home sealed in the wax of a pack of cards

On my eleventh birthday, before my own found air.

I have grown and lost beards since then

Grown and lost so many things.

You were eight years older than me, that day. Eight years.

You are twenty younger than me now.

Someday my own skin will recede

And your mustache will still be there

Undying, untested, unashamed.

The exact origins of the term hot stove are uncertain, or at least uncertain enough as to be left a question in the Dickson Baseball Dictionary. The moment it gained widespread popularity, though, is clear: Hall of Fame historian Lee Allen’s book The Hot Stove League, published in 1955.

“If winter, for the baseball fan, is a time to look ahead and visualize successes for his favorite team, it is also a time to look back at the bittersweet path, to review the triumphs and the heartbreak of the past. Baseball knows no season, really. But fortunately there is a lull in the action that permits the fan to take pause and consider what he has seen and read about. There is no way of measuring the heat generated by each annual loading of the old, hot stove. No one has ever tried to show which was the greatest winter of all for the game’s devotees… But for sheer excitement, controversy, gooseflesh thrills, and variety of accomplishment the Hot Stove League has never provided anything to equal the year of 1884.”

That paragraph is from a chapter titled “The Hottest Stove of All,” grappling directly with the idea introduced in the book’s title. But this hot stove is so fundamentally different from today’s as to be almost unrecognizable. It is not about deal-making, because there were no deals in a game that was decades away from recognizing free agency; it is not about action, because what form would that action even have been able to take? Allen found the 1884 offseason’s stove so hot not because anything special happened. It was hot because of the things that had already happened—recent expansion of the game’s three biggest leagues, Old Hoss Radbourn’s 59 victories, various other standout performances and minor controversies. The stove was hot because there was so much to talk about and think about. That winter would be a baseball void was a universally accepted condition of the sport; the heat from the stove was just however you might choose to fill it.

Right now, the stove is cold. This stove is different from Allen’s: this one needs money to burn, and there is plenty of money around, but no one will light a match. Everyone has spent the offseason remarking on how cold the stove is—measuring the precise degree of coldness, offering solutions for heating it up, arguing over whether it is truly and permanently broken or whether it’s a temporary quirk of circumstance from decisions made by the group of men who can relight the pilot. The stove’s value comes only from what it can cook; it does not matter whether it might be a nice place to sit and warm your hands for a bit and think. No one wants to make time for that, anyway.

There is nothing but talk now. Once upon a time, this was what they called hot.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now