The heaviest snow Durham had in eighteen years fell a couple of weeks ago. It briefly quieted the city’s limbic system, which has been upheaved by development for a few years now, and lately with a frenetic intensity: Durham is a riot of cranes, excavations, ugly construction, overpriced restaurants, and the destitute flung into the chaos. The city is under full-body forced growth and strain, and it will only increase over the next several years.

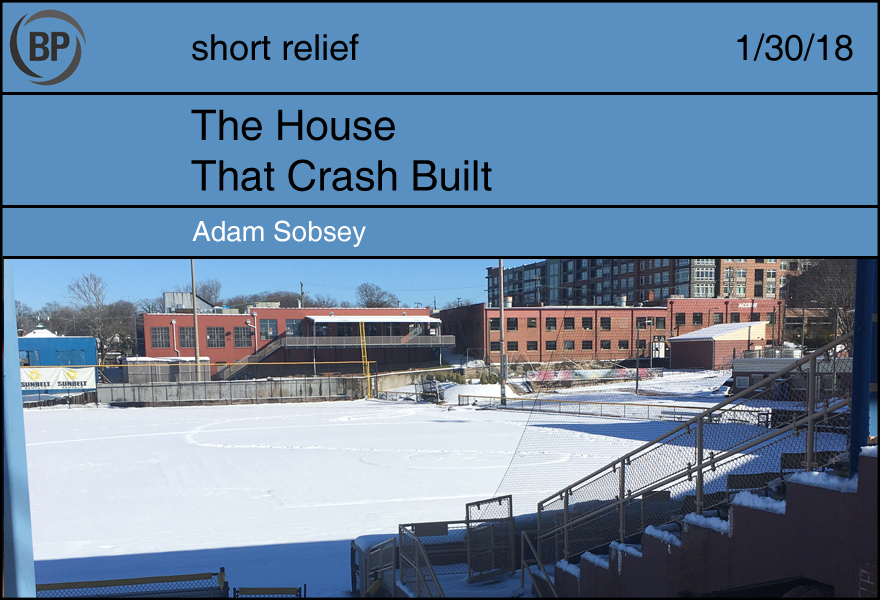

Historic Durham Athletic Park—the Bull Durham ballpark, the House that Crash Built—was still covered with snow for days after the rest of downtown had been cleared or melted of cover. The ballpark is in the center of the city, about a mile from the (no longer) new one where the Bulls now play. Without question, Durham Athletic Park is more than the city’s muscle memory, and more lifegiving even than its heart: it is Durham’s glands, its very genitals, hot with life even as it lies under the snow. If football is violence, then baseball, as Bull Durham persistently demonstrates, is sex.

The ballpark occupies land once unwanted, now valuable. The college team that plays here isn’t enough to keep Durham Athletic Park alive with only baseball. Nor does the occasional festival of blues or beer improve the ballpark’s life expectancy in its present form. It simply can’t hold out much longer. Every week, it seems, a new building is thrown up right around it, each one closer than the last, encroaching, menacing, smelling blood. The infidels are poised to sack this church of baseball.

Perhaps they can be stopped if the ballpark is transformed. A few years ago in Indianapolis, derelict Bush Stadium was turned into apartments. (Here is an excellent short documentary about that, by a pair of college students.) But Downtown Durham—the United States of America—doesn’t need more private space. It needs common ground. Our downtown has no city park to speak of. Make one out of the ballpark. Let there be frisbee in the outfield, a climbing wall up the left-field fence, picnic benches under the grandstand for hot summer days, Shakespeare on the diamond at night. Reopen a snack bar on the concourse, or park food trucks right on the warning track. We need a place where everyone can go. It’s already built. People will come.

It’s Tuesday and Trevor has booked a good, all-day job, one that will let him pay for a new batch of headshots or re-up at the gym for another year, he’s not sure yet; all he knows is he is going to be a fan of every MLB team, all in one day.

That’s how the casting agent had pitched it to him, at least. I hope they don’t make you wear a Red Sox jersey, she’d cackled, although I guess you have to wear it if they do! Trevor had laughed. He hadn’t reminded her he was from Omaha. A job was a job.

It turns out Trevor will not be wearing any jerseys, just a white t-shirt the jersey would be photoshopped over. “Just like how they do it with players!” says the photographer cheerfully, and Trevor wonders what that would be like, to wake up one day and find out you had been shipped cross-country. Trevor decides if he was a player he would probably get traded at least twice. He is good at lots of things–that’s the feedback his agent gets–but he knows he’s not as good as some of the other guys he goes out on auditions with, who suddenly stop auditioning because now people are calling them. The world is made up of those who want and those who are wanted, and Trevor knows, deep down, that just like most people, he will always be more of the former.

This is the kind of thinking his agent is always encouraging him to do, thinking it will help him book more jobs: become the character before you even step into the role. His agent does not think he is very smart, Trevor can tell; she sends him on jobs like these, modeling jerseys for the MLB shop, and not ones where he has to talk much, if at all. Maybe if he shows her how he can become a baseball player, even in a print ad wearing a white t-shirt, she’ll send him out for some bigger, better roles. So Trevor decides to do something else he doesn’t usually do–he asks questions of the photographer.

The first one is easy. “The Washington Nationals,” says the photographer, and Trevor doesn’t even have to ask. He closes his eyes for a moment and imagines Bryce Harper.

The next one isn’t any harder. Trevor’s most recent ex was from San Francisco and loved Buster Posey, who Trevor finds is just Bryce Harper, Less Shoulders:

Things get a little tricky when the photographer calls for the lights in the industrial warehouse they’re shooting in to be turned up a little to mimic the hot Texas sun. All Trevor remembers about the Rangers is their players were involved in that fight where Jose Bautista’s helmet got punched right off. Cockiness, he decides, and gives some Attitude Shoulder.

Trevor’s boss at his temp job at a startup in DUMBO before he quit to do this full-time it was a Cardinals fan, and Trevor takes a moment to summon his face and body language, the impression that used to kill at Friday happy hours. “Excellent,” exclaims the photographer.

But then things get harder. Trevor doesn’t know anything about the Diamondbacks, and decides to brave a question. “So, uh, who is their best player?” The photographer, switching out a lens, says something about All-American, and a name that sounds vaguely familiar to Trevor but maybe he’s thinking of that guy who was an actor in the 90s? Too late, Trevor realizes he is just doing Buster Posey But Concerned About The Growing Opioid Epidemic.

Trevor has never heard of the Cincinnati Reds.

“So the deal with the Mariners is…”

“They haven’t made the playoffs in a decade and a half, and haven’t made any significant additions to their starting rotation. Also, they wear teal, and that gets people really worked up.”

“And the Rays?”

“Take the Mariners, but with a smaller payroll. And they play in a dark, airless dome.”

Trevor waits for them to get to a team he knows–one of the New York teams, or even the Red Sox so he could joke about it with his agent later, or maybe the Dodgers; a friend had given him a Dodgers cap when he thought he was moving to LA to be a movie star. He waits and waits.

They never do.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now