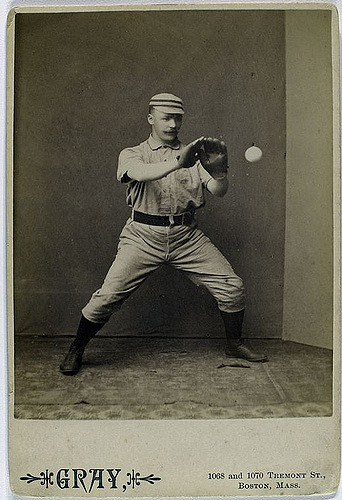

The nineteenth-century ballplayer: mustachioed, musky, Irish or perhaps aggressively not Irish, brawny, inclined to swearing and drinking, did I mention mustachioed?; an image, conjured rather easily due to the proliferation of photographs of late-nineteenth-century male baseball players; the kind who fizzle and pop into the half-lucid late-night dreams that are Ken Burns’ Baseball reruns at two o’clock in the morning.

I want you to close your eyes and imagine one of these men fielding a fly ball after one bounce.

It’s perhaps easier to envision a child fielding the ball in this way, since most adults we imagine as baseball players are professionals who have long since developed both the skills and the behavioral conditioning to catch a ball on the fly. In the middle of baseball’s formative century, about 150 years ago, there were far fewer adult professionals and many more adults playing the game of baseball recreationally, or for exercise.

Henry Chadwick, the “unstinting baseball propagandist,”(1) saw adult men catch the ball on a bounce many times in the 1850s and 1860s as he observed, annotated, schemed, and conjured up language and statistics and rules for the game of baseball. And Chadwick hated that these men would field the ball on one bounce. Until 1864, such a play functioned identically to an out caught on the fly; Chadwick and many of his contemporaries scolded the bound rule, as it was known, as “childish.” It was “a feat a boy ten years of age would scarcely be proud of,” according to Chadwick, and the box scores he developed demarcated differences between fly catches and bounce catches.(2) He was joined by many others who sought to make the game and its attendant imagery and culture into one for adults, and specifically, for adult men. The game’s premier clubs, usually located in or around New York City, sometimes played games with the fly rule as a practical exhibition of its purportedly superior (and masculine) quality.

The comparative skill needed to catch a ball on the fly as opposed to on one bounce is hardly arguable, and Chadwick believed that molding the game’s rules towards skill, and not merely exercise or recreation, would produce a finer game. By the end of the Civil War, professional and amateur teams throughout the United States largely discarded the ability to catch the ball on one bounce for an out, and the fly rule’s hegemonic rule began.

Chadwick’s motives, of course, are a point of interpretation: his vision of organized baseball was that of highly skilled, respectable men, and that vision, like his desire to rid the game of the bound rule, would eventually result in victory. At a time when baseball’s future was at stake—who would play it, where it would be played, how it would be played, and what it would represent—Chadwick made war on the bound rule, in pursuit of his manly ideal.

1. Warren Goldstein, Playing for Keeps: A History of Early Baseball (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 55.

2. Goldstein, 49-50.

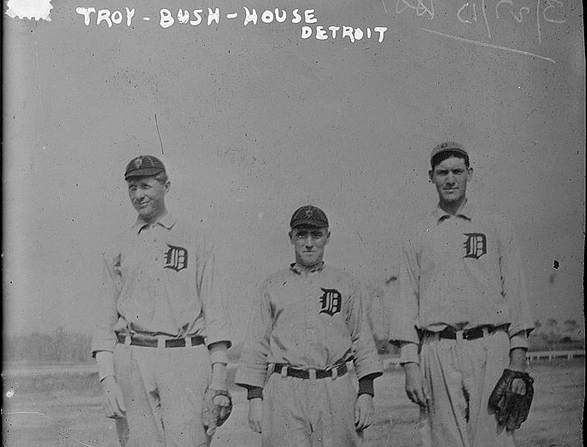

Robert Troy spent most of his life waiting. He was born in Germany but his family moved to a town called McDonald, boasting (then and now) a population of 2,500 people. Standing 6-foot-4 at a time, a hundred years ago, when that was a height of note, Troy pitched for the semipro county ballclub in his youth and towered over them in every sense of the word. The Phillies heard the stories, signed him for a tryout in 1910, but he didn’t surprise the spring; he was too wild, it was reported, and the 21-year-old “acted too much like an amateur on the ball field.” He spent the next couple of years bouncing around the minors, losing more than he won, getting sold from one town to another, waiting for the pitches to go where he aimed them.

It was in the Class D Southern Michigan League, the lowest pro ball there was, that they finally did. He led the league in both wins and strikeouts, and provided an exclamation point in the form of a doubleheader, where he spread eight hits across two back-to-back shutouts. Still only 23, it was enough to entice the Detroit Tigers to sign him to a contract and give him his big break. The opposing pitcher: Walter Johnson.

Troy dueled the Big Train to a scoreless draw for six innings, and if the wise men who invented baseball had been of a different mind, Troy’s life would have drastically altered. Instead, he went out to pitch the seventh, and gave up four runs. Devastated, unable to accept his failure, he left the team, and with it his major league career, a single start and a single loss. He fled back to the minors, where the teams began to get sold before he could escape them, until Troy’s baseball career vanished from the back pages into general store banter.

And then America entered the war, and then Robert Troy went to meet it. Now nearly thirty, he was made sergeant and assigned to lead the boys he once played ball with on the pebbled fields of Pennsylvania. And once again life became about waiting: waiting for supply lines, waiting for the push, waiting for the silence of the mortars and the signal to climb out of the trenches, out of safety and into the barren, cratered hell of no man’s land, into the machine guns and the barbed wire and the mustard gas. The attack led into the Argonne forest, but the title is a morbid joke; the trees had been blown apart by mortar, only the trunks still standing, like prefabricated tombstones.

The call came and this time Robert Troy did not run away. His division, the 80th, was the most highly-rated and successful of the American forces. They alone were called into action on three separate offensives, they alone succeeded in all three.

It was in the last of these, only a month before the armistice, among the noise and the smoke and the screams, that Sergeant Robert Troy was shot in the chest and killed. There are stories of songs of boys sent off to die, but by October 1918, Troy was no longer an amateur on the field.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now