Perhaps since the dawn of baseball, coaches have been asking pitchers if they’ve thought about throwing from a different location on the rubber. Start on the third-base side. Start on the first-base side. Stand in the middle. For almost as long, observers have been trying to figure out what difference it makes.

Anecdotally, you can come up with all sorts of ways the changes make sense. Man, if that southpaw stands on the first-base side, it’ll look like every pitch to lefties is coming into their ear. And when better results follow, beat writers and analysts and the pitchers themselves hail the change as the elixir that solved whatever ailed them.

“I’m a big believer in trying something, and if it doesn’t work, you go back to what you were doing,” then-Nationals reliever Blake Treinen said in 2015, after moving to the third-base side. “But this has worked. It hasn’t made me worse, so we’re going with it.”

Twins reliever Tyler Duffey offered a similarly inspiring endorsement of his minuscule but momentous journey across the mound early in 2017—one brought on by a chat with Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven. “It’s seemed to work so far.”

The numbers have not been as easy to wrangle as the anecdotes, though. Back in 2008, Josh Kalk (who has since worked for the Rays and was recently hired by the Twins) asked how release points affected success. After diving in about as deep as he possibly could at the time–the dawn of pitch tracking–he emerged with little more than a series of correlation charts that could have doubled as shotgun splatters, and words of caution for hurlers lapping up optimistic tales of mound shifts that led to glory.

“While you will hear from time to time that a pitcher is extra difficult because he varies his release point or because of an extreme release point,” Kalk wrote, “it doesn’t appear that either of these things makes a difference at the major-league level.”

***

When the Chicago Tribune set out to detail the financial success story that was McDonald’s in 2004, it acknowledged that “hundreds of changes, big and small” had led to a significant, surprising turnaround. But it led with that most mouth-watering of tidbits: A longtime executive, plucked out of retirement to aid the company, had rediscovered and re-implemented the original recipe for the “special sauce” that comes on Big Macs.

Made famous mostly by a 1975 advertising campaign, the formula had been changed somewhere along the line. What better to illustrate the global fast-food powerhouse’s resurgence than this easily identifiable tweak?

***

As you hopefully read in the excellent piece outlining BP’s latest research on pitch tunnels, we’re advancing toward better understanding these changes by using the batter’s perceptions as a starting point.

Based on that framework, you start to envision how this should go. And some things come out just the way you’d think: Right-handers have a more difficult time differentiating between Chris Sale’s pitches, for instance, because both the sliders and the fastballs look like they are breaking in from right field until one whizzes past letter high and the other hits them in the foot. Stephen Strasburg’s fastball and slider are indeed impossible to separate early in their flight, etc.

Other upshots are less intuitive. Rich Hill, who famously throws his curveball from all sorts of arm angles, moved to the third-base side during his absurd ascent toward ace-dom. If you’re trying to visualize it, that would be the opposite of what you’d expect to “create difficult angles” like the ones Sale uses. He has essentially eschewed tunneling altogether, but found enough control (usually) to allow his stuff to play.

One of the most attention-grabbing pitcher adjustments in recent years was Mariners lefty James Paxton’s shift to a lower arm angle. In making that change, he changed not his physical position on the rubber, but the direction of his stride, effectively altering his release point.

Since his 2016 emergence as an exceptionally good starting pitcher, Paxton has been striding toward first base, his arm extending out in that direction as he goes, and then firing the ball back toward the plate.

One result: His sequences that go from four-seam to cutter or vice versa are among the most deadly and deceptive on record. To lefties, they may look like a train passing by the nose of their car. To righties, they are flies buzzing straight into their faces, but veering in different directions at the last second.

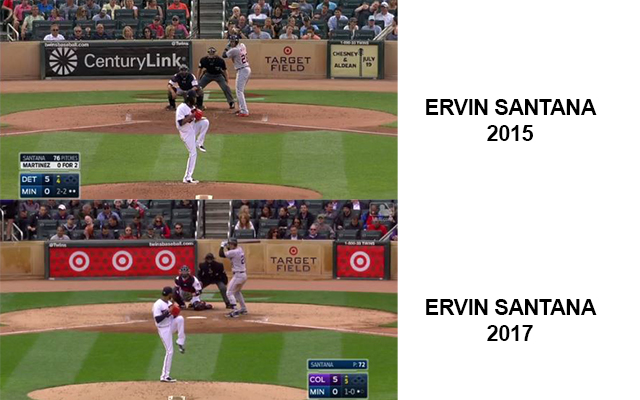

The Twins’ Ervin Santana–who has experienced a minor renaissance in his mid-30s–made serious gains in a different way. A right-hander, he also moved his release point toward first base (the same direction the lefty Paxton went) and reemphasized his sinker at the same time. As it turns out, it looks exactly like his slider in early flight.

The pitches in tandem have been elite in just about every metric for tunneling. They reached their maximum point of differentiation as late as any sinker/slider sequence, and that maximum differentiation is still not very large. Thrown back-to-back to right-handers, the complementary pitches end up 17 or 18 times further apart at the plate than they appear at the hitters’ decision point–elite not just among contemporary pitchers wielding the combo, but among those who’ve done so since 2008.

***

The funny thing about Googling “secret sauce” or “special sauce” is that you are not presented with rollicking tales of intrigue. No yarns are spun around corporate spy craft or culinary recon. There is no hand-written family formula in a safe. Instead, precise directions for making “special sauce” appear, down to the teaspoon.

There are, in fact, a lot of ways to make secret and/or special sauce. They all seem to be various shades of orange, just viscous enough to dip French fries in, with speckles of darker orange or chunky elements mixed in to meet the creator’s tastes. Some of them–like the ketchup/mayonnaise blend that has enriched the family of the Utah restaurateur who thought better of giving it a transparent name–are stupefying in their simplicity.

***

Duffey, the Twins reliever whose early results were enough to validate his tweak, was actually taking fairly exceptional action. A righty trying to cure platoon issues against lefties, he decided to simply use two different sides of the rubber, depending on the batter’s handedness. It’s an uncommon strategy, although one that Brewers starter Chase Anderson also took to in the middle of 2017, and one that has some history in Minnesota.

When Max Marchi cast a critical eye on Francisco Liriano’s mound positioning in May of 2011, the slider-whipping lefty had long used that unconventional, batter-dependent tactic. Thinking it could be behind Liriano’s command issues, a pitching coach asked him to stick with one side. After a few poor outings, he abandoned the idea and went back to creating bifurcated release point charts, immediately throwing a no-hitter that, middling as it was, likely closed the book on the issue. No one, remember, had any great way of figuring out what was happening.

Six years later, after Duffey’s rendezvous with Blyleven–who noted Liriano’s test run from the broadcast booth–we had a case where this potentially brilliant strategy could get a thorough look. In moving to the far third-base side against lefties, Duffey did find a modicum of success, but it’s not clear the move was behind it. His pitches were 12.3 times further apart at the plate than they appeared at the decision point for lefties, just a tic above the league average, and only a modest improvement over 2016. He appears to have abandoned it in September.

***

A few years back, I was working at a newspaper in Roanoke, Virginia. There was a bar downtown that I would frequent with co-workers. Aside from the self-explanatory main attraction, this bar’s calling card was burgers, fries, and the “special sauce” that came with them. Although I don’t think any of us had ever thought twice about the sauce on Big Macs, this sauce could have convinced us to eat just about anything. We developed a natural curiosity about it, and there is at least one Reddit thread to prove we were not alone. One night I even stowed away an extra cup and took it to my apartment–telling myself I’d get to the bottom of what was in it.

Like generations of pitchers and those who attempt to help them, I had no way of accomplishing that goal. It took me less than 24 hours to come to terms with that fact and pull the sauce out of the fridge to enhance the chicken tenders and fries I’d made from a box in the freezer. And while it served the general purpose, it wasn’t the same. Outside its intended pairing, it wasn’t that special at all.

The secret about special sauces is that they’re just shallow cover stories, each and every one. It’s not just the content of the condiments that matter, but the way they interact with their accompanying fry or burger.

Pitchers are neither fries nor burgers, but they have a similarly complex relationship with the little things that could make them better. What BP’s new numbers (and, to be sure, related research within clubs) allow for is some demystification of the development process for those who truly want to figure it out. Instead of sampling every arbitrary tweak they come across, pitchers are hopefully taking into account what worked for others with similar repertoires or body types or deliveries.

Yes, there is an almost magical allure to inexplicable goodness–providing us with stories of Dave Duncan and Ray Searage–that would be missed. And yes, it may be endangered, in a sense. But it’s nowhere close to extinct. Pitchers who do find more personalized, more straightforward paths toward their ideal selves, after all, can still say whatever they’d like in interviews. Something tells me they still won’t broadcast their secrets.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

The answer I'll give is: Assessing the injury risk of any one thing against the broad sample of "all pitchers" is basically impossible and mostly dependent on the person, not the idea.

I think pitchers should mostly be seeking out a balance between what feels the best and most natural and what works. It's extremely complicated, basically.