A year earlier DeGaulle fled Paris, resigning rule to the feuding students and labor leaders that took the streets as their own. Across the United States there were bombings and marches, and a year later four American college students would be shot dead on a campus by armed guardsmen, protesting the Vietnam war.

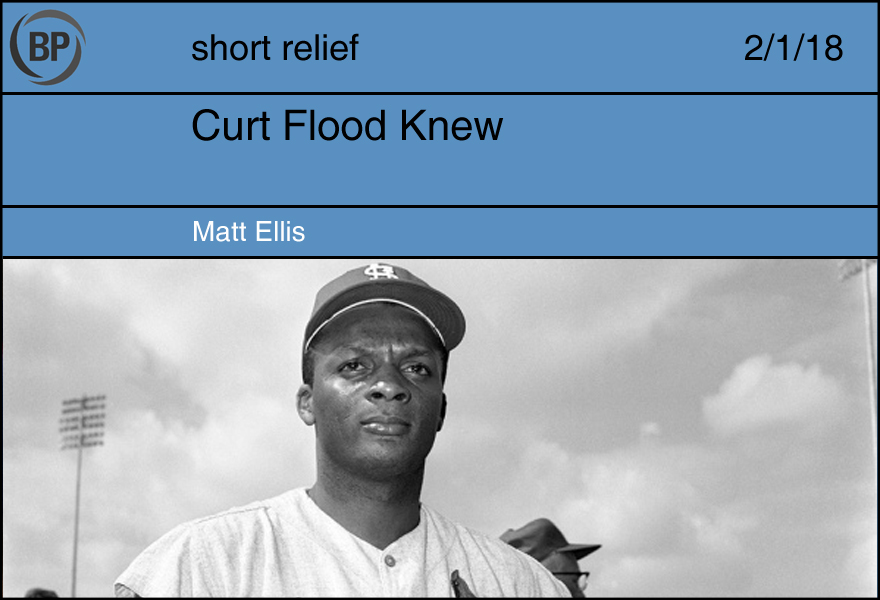

But instead it was December 24th, 1969. Five months earlier a man walked on the moon; two months, the Mets with one of only two championships in their franchise’s entire history. That day, Curt Flood wrote a letter to commissioner Bowie Kuhn demanding to be declared a free agent after refusing a trade to the Phillies (which, I mean, I’m a historicist too but come on). Everyone knows what happened next: Flood cited the growing black radicalism of the 1960s as his inspiration to challenge the reserve clause, and his case eventually went to the Supreme Court only to stand unchanged. The man played 13 more games in his entire life before being effectively blacklisted, but the event nevertheless paved the way for an eventual free-agent system to emerge–a system which would go on to influence the construction of every other major American sports league to the modern day.

In one sense, it was long overdue. The history of labor movements in the United States alone runs through something that looks vaguely like wealthy capitalists trying to satiate militant labor in the late 19th-early 20th Centuries, ceding ground to a powerful union movement through the 1960s, and finally restructuring the global economy to precarity and market efficiency after the near-bankruptcy of New York in the mid 1970s. It is in a sense it is ironic, then, that baseball essentially ran its course in the complete opposite direction, players finally only earning the true power of demanding compensation indexed to their output when deregulation began to sweep the post-manufacturing economic market in the 1980s.

Today, though, we are left with something entirely different. An owner-friendly CBA in concert with a lack of need to rely on expensive, established players emerged in the wake of the Cubs and Astros’ recent World Series victories, and we once again are facing what could be a troubling rearrangement of the baseball labor market, one which could bring us not simply back to the precipice of 1994, but perhaps to an even worse place: one which doesn’t end up with a momentary stoppage of work and instead to a new permanent class of temporary, underpaid workers producing more value for their work than they end up receiving through their entire careers, useful only for eight seasons before being disposed for the newest piece of cheap plastic.

Many words will be written about the impending impasse facing baseball, but I can’t help but think about the final years of Curt Flood’s life after he almost single-handedly did more for labor than anyone in the history of the game. After retiring and earning a paltry sum on a memoir, Flood purchased a bar on an island in the Mediterranean. After a brief attempt to return in the broadcasting booth, Flood finally died in 1997 due to complications from throat cancer. Meanwhile, baseball was three years removed from one of the biggest labor crises of the game, and the American economy was churning forward after the “final” victory of capitalism in the Cold War.

At that moment, the tumult of the sixties was all but unthinkable–there were no Weathermen, no mass strikes, no Pan-African movements holding legitimate power against a continually encroaching West that sought to take all it could, and make all it could. The worst was over; Ripken had saved the game with his streak and Sosa and McGwire were breaking records and wearing cereal boxes and local 10 o’clock news segments. It couldn’t get worse. How could it?

But Curt Flood was nowhere to be seen once the congressional hearings started. He occupied a few minutes in Ken Burns’ film, and was then quickly forgotten. What better way, then, to hide the biggest threat facing hegemony than a leaf blossoming brown.

But someone, somewhere, today, is Spring.

(photo credit: © Brett Davis-USA TODAY Sports)

MLB proposes 11th inning of All-Star Game start with a runner on second base. Your ideas are stupid. My ideas, though, my ideas are good. Here are my ideas:

- At the start of every prime-number inning, you get a runner on every prime-number base.

- At the start of every inning that people always think is a prime number but isn’t, you get rapped across the knuckles.

- At the start of every perfect-cube inning, you get a runner on every perfect-cube base.

- At the start of every inning that is both prime and a perfect cube, you get a glimpse of nuclear winter.

- At the start of every irrational inning, you get a runner at every point along the line between first base and second that corresponds to an irrational number if you take first base to be zero and second base to be one.

- At the start of every imaginary inning, the defense gets a unicorn in the outfield. If you eat the unicorn, you gain terrible knowledge. If you do not eat the unicorn, you get a manticore at third base.

- At the end of every inning before the last one, you erase all your runners. From existence.

- At the end of the last inning, your runners ascend to an exalted plane; this will seem to the fans, laughable mortals, the same as the erasure of the previous and subsequent runners, but the truth for those of us who know will be glorious and triumphant.

I am in a box. As far as I know I was born in this box and I will die in this box. I have never seen anything outside the box. It is just me, here, and a few inches of room between me and the walls. Sometimes I wonder how I haven’t suffocated by now, and then I wonder how it is that I know I should have suffocated by now, given that I don’t know anything other than this box. Sometimes I become aware of my own thoughts, which feature concepts like suffocation, and wonder where I got the language to think them from. Occasionally I wonder how I know I am enclosed—why I seem to have some awareness that there is something outside where I currently am, though nothing I have ever experienced suggests this to be true. These moments of dissonance, never resolved, are the most interesting things that ever happen to me. They are terrifying, and I try to forget them as quickly as possible.

At some point I indulge the thought of being enclosed for a little too long. I decide to try to break the box. I have no real expectation of anything happening. Still, I begin to feel panicky. I shift my arms ever-so-slightly, and something changes. I can’t quite tell what is different at first: my surroundings look the same, feel the same. It takes me a moment to realize that I am hearing something, an overwhelming noise that separates itself gradually into many noises interacting with each other. Voices and voices and voices, so close they must be right beside me. I am surrounded by people. Have I always been surrounded by people?

My chest clenches. I try to move more, but I can’t. I try to see if I have created some opening that is allowing the sound to get through, some opening I could exploit to escape, but there isn’t, and I can’t. The voices are all speaking the same specific language, with a lot of words I don’t understand and some that I do. I understand hit and throw and run. There are “strikeouts,” and there are “basepaths,” and there are “middle relievers.” Everyone around me is so excited for this strange thing that they are talking about, this thing with hitting and throwing and running and all the other words I don’t know. It’s starting soon—that’s the main thing. It’s starting soon. Everyone is so glad it’s starting soon.

I wish I could see this thing everyone’s talking about, or even just ask them about it. Some of the voices are very angry or sad, but they all seem so engaged, and they all have so many other voices to talk to. That seems like it must count for something. But there’s nothing I can do. I am still in the box, no better or worse off than before. Around me, the voices are counting down the days.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

How many ballplayers today, black, white or brown, can make that connection? The largely overlooked Curt Flood probably did more for the well-being of professional ballplayers than anyone in the history of the game. He ought to be put on the same pedestal as Robinson, but is sadly remembered as little more than a footnote in the pro sport labor wars, the little guy who dared stand up only to be ground into oblivion by unforgiving corporate machinery and a government that chose money and power over individual freedom. Flood is held up today more as a cautionary tale than what he really was, a man who changed the world and paid for it with his life.