This week, players, agents, and others have begun calling for the Major League Baseball Players Association to engage in a boycott of reporting to spring training or some other form of group protest to make a statement against the lack of activity in the free agent market this offseason. Others have voiced their additional displeasure over the pace-of-play rules that commissioner Rob Manfred has announced that he intends to unilaterally implement.

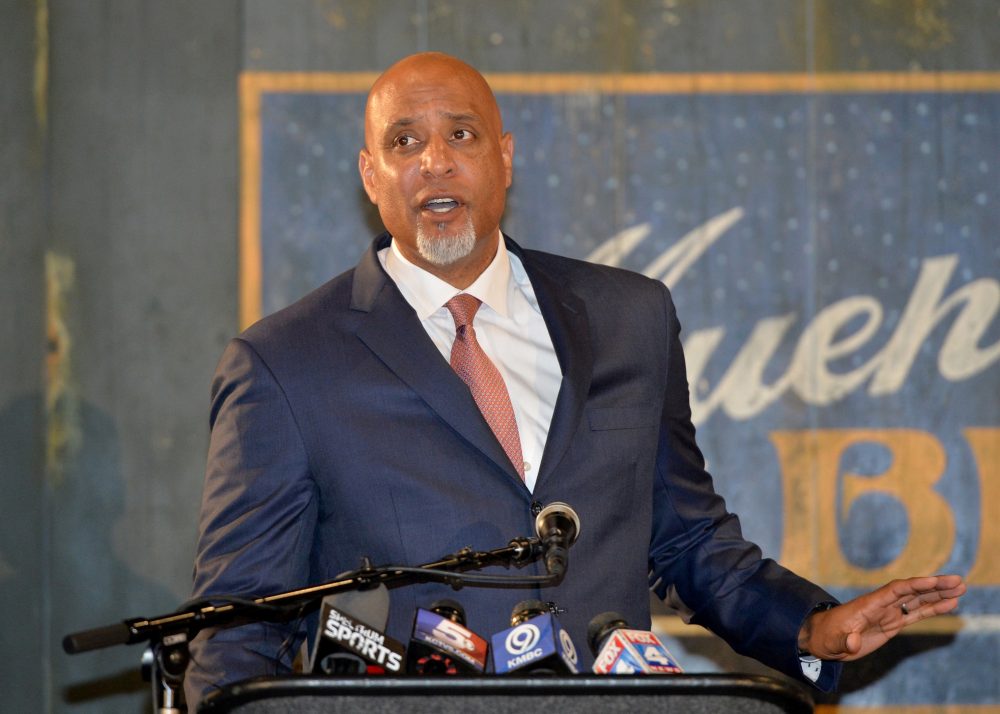

Tony Clark, the MLBPA’s executive director, issued this statement on Sunday:

Recent press reports have erroneously suggested that the Players Association has threatened a “boycott” of spring training. Those reports are false. No such threat has been made, nor has the union recommended such a course of action.

While the union is made up of the players, individual players, unless elected, do not represent the union, and this distinction is important with regard to statements about players withholding their labor during spring training. The union’s clear and unequivocal statement may look like they are turning a deaf ear to individual players’ pleas, but they have a very good reason.

Clark followed up on Tuesday with a statement that expressed the players’ frustration, but reiterated that there would be no boycott, but this time phrasing it positively (emphasis added):

Pitchers and catchers will report to camps in Florida and Arizona in one week. A record number of talented free agents remain unemployed in an industry where revenues and franchise values are at record highs.

Spring training has always been associated with hope for a new season. This year a significant number of teams are engaged in a race to the bottom. This conduct is a fundamental breach of the trust between a team and its fans and threatens the very integrity of our game.

If the players and their agents were truly asking for a “boycott,” it would be for fans to not attend spring training. By saying that players should not report to work, that is withholding of labor, which the law treats as a strike, not a boycott. And there are legal restrictions on the right to strike. The primary one is the bargaining cooling off period in the National Labor Relations Act, which governs labor relations in the private sector, other than rail and air.

The cooling off period provides that if either party seeks to modify or terminate an existing Collective Bargaining Agreement, including upon expiration, it must give 60 days notice to the other party and continue work during this period without resorting to a strike or lockout. (Spring training reporting begins February 12-14, depending on the team, with a mandatory reporting date of February 24).

The party desiring modifications or termination of an existing CBA must also notify the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service and the appropriate state agency within 30 days after giving the other party notice of the existence of a dispute. This is why nearly all strikes occur after the expiration of a CBA. Having not served notice, if the union were to endorse this strike, it would be in violation of the NLRA. But, equally important, if it were to serve notice now, on what would it be serving notice? In this case we do not have expiration. In fact, the MLBPA and the clubs negotiated a new CBA that became effective December 1, 2016, lasting through 2021.

While bargaining is recognized as a continuous process throughout the duration of a contract, the duty to bargain only extends to those matters that were neither discussed nor embodied in any of the terms and conditions of the CBA. Neither party can be required to discuss or agree to any modification of the terms and conditions contained in a contract for a fixed period if the modification is to become effective before the contact expires or before the matter can be reopened under the provisions of the contract. The mechanics of free agency are covered by the 2017-2021 CBA, so without a duty to bargain the union could not even serve such a notice, much less call a strike to protest the lack of free agent activity. The penalty for such a strike is that the players would lose their status as employees under the NLRA. In effect, their individual players’ contracts would be voidable.

Going back to the distinction between the players and the union, none of this is to say that individual employees cannot decide when to report to spring training in accordance with the provisions of the CBA, which requires reporting no earlier than 33 days before the start of the season. However, there is a difference between individual actions in compliance with the CBA and concerted activity to withhold labor endorsed by the union.

While the notice period prior to a strike is applicable for economic strikes, it is not for a strike due to the employer’s commission of unfair labor practices as defined by the NLRA. And, there is a duty to bargain mid-term over subjects not contained in the CBA. So, would the commissioner’s announcement of his intent to unilaterally implement pace-of-play changes constitute a ULP, making a strike legal, even without notice? It has been widely reported that the 2017-2021 CBA allows the commissioner to make changes to the pace-of-play rules with one-year’s notice to the MLBPA. This subject, too, is covered by the CBA and would constitute a clear and unmistakable waiver of the duty to bargain. I do note that the CBA article on rule changes is identical to the previous CBA.

Some have publicly criticized the MLBPA for various provisions of the 2017-2021 CBA. Normally, there is some segment of a union’s membership that is vocally disappointed with one or more terms of an agreement. Sometimes that displeasure can spur mid-term changes. Other times, it can lead to political changes within the union. But, under these circumstances, it cannot lead to a strike.

With that said, all agreements have some unintended consequences. Sometimes those consequences have negative implications for both parties and require them to revisit the terms. Other times, one party is satisfied with the result, and because there is no duty to change, it remains in effect for the duration of the agreement. That is likely the case here with regard to free agency, but it may result in a more aggressive posture or even a more hostile MLBPA leadership in the next round of CBA negotiations.

Eugene Freedman is Special Counsel to the President for a national labor union. He has been on eight term-contract bargaining teams and negotiated countless mid-term agreements.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

This contractual language reinforces the legal requirements I mentioned above when I wrote: Neither party can be required to discuss or agree to any modification of the terms and conditions contained in a contract for a fixed period if the modification is to become effective before the contact expires or before the matter can be reopened under the provisions of the contract. The mechanics of free agency are covered by the 2017-2021 CBA, so without a duty to bargain the union could not even serve such a notice, much less call a strike to protest the lack of free agent activity.