On Friday night, the staggeringly popular George Saunders gave a reading and a brief talk about writing in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The event was part of Saunders’ tour for his Man Booker Prize-winning novel Lincoln in the Bardo. The story is one that encourages a reader to get caught up in the craft, to figure it out; it’s a book that needs figuring out, difficult to read in fragmented time and in the vaguely distracted way so many of us do so many things, even those activities we love.

It’s telling that Saunders didn’t actually read from Lincoln in the Bardo when he did read. There seemed simply too much to do for such a reading to work: too many voices, only one mouth. The novel contains 166 speaking characters and is rife with ghosts. Spun from a historical fragment regarding President Abraham Lincoln’s grief following the death of his son, the novel treads the spaces between history and myth, research and wild invention. The title itself invokes the between-state: “bardo,” in Tibetan Buddhism, refers to the state of the soul between death and rebirth, and might be invoked in other contexts for other liminal states—between dream and wakefulness, the here and the hereafter.

This week pitchers and catchers will finally report, the beginning of recognizable baseball activities, but let us not fool ourselves: this is not baseball yet. Spring training, by its very nature, is not baseball; it’s not meant to be; we are encouraged on every front not to trust it. February is marked by voices we won’t hear all summer. Though they might echo back late in the season, or be shouted out from some shadowy place—in pleading, in hope and ardor—many of them will be as ghosts, haunting memory alone. Injury will quiet some; the swansong for others will not play. For others, their entry is not yet come, and for some it never will.

But for now, the place between is sweet, if overwhelming—polyvocal. Baseball in the bardo means that nothing has yet been decided—nothing has to be, yet. We’re free to listen, to imagine, to make our own conjectures about how the story might come together.

There are times, as a writer, when the writing almost feels unnecessary. It often happens when I am sitting on couches. It’s a feeling of empowerment, the mental equivalent of the feeling when the bat is on the shoulder, muscles coiled but not strained, ready to strike. I imagine musicians get this feeling more than writers, or at least with a greater density: the knowledge that you are about to knock them all down.

As I write this, I must confess: this is not one of those times. A practiced author has tricks to avoid writer’s block, stores up grain for the winter and revisits old content and swims through. I write principally for myself, mostly to attain that feeling. But when artistry is unattainable, the alternative is to be useful. I am going to be useful today, by discussing the relative merits of a certain portion of the Topps All-Rookie Team.

Topps, as you’re probably aware, is a baseball card company. Each year since the early sixties they’ve selected an roster of the best rookies, by position, from major league baseball. Sometimes those selections would go unannounced, strangely. But other years, a child ripping open the wax of a pack of cards might be fortunate enough to glimpse the golden bowl of the All-Rookie, an official invitation to hope.

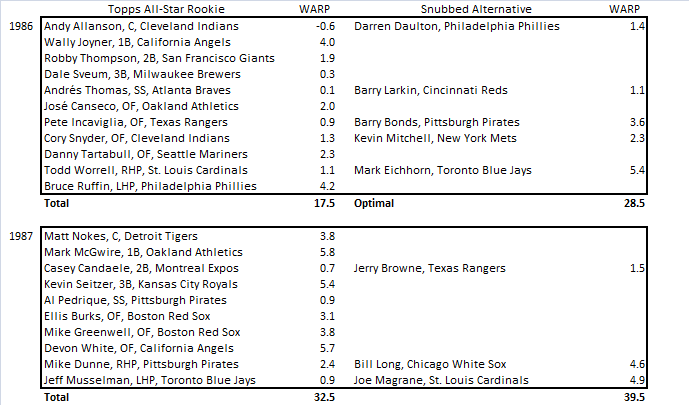

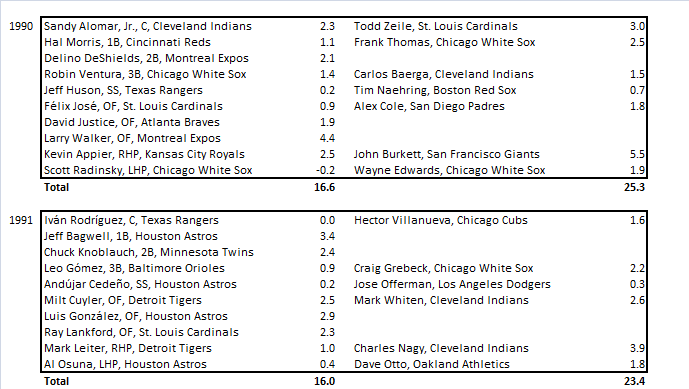

I’ve chosen to review Topps’ choices from 1986-1992, the height of the junk wax era, to see how they did in the fullness of time. Remember that each season is reflected in the next year’s cards – thus, 1986 would be the beautiful woodgrain of 1987 Topps, and so on.

It’s an interesting coincidence that the height of the junk wax era, 1987 and 1988, offered the strongest rookie crop of the era (1985, with Clemens/Puckett/McGwire, is probably the true king). It’s actually impressive how many Topps got right without the benefit of such things as, you know, OBP. But that sub-replacement Andy Allanson is an eyesore, and Mark Eichhorn is the single biggest snub, both in overall value and value lost. Mark Eichhorn is amazing.

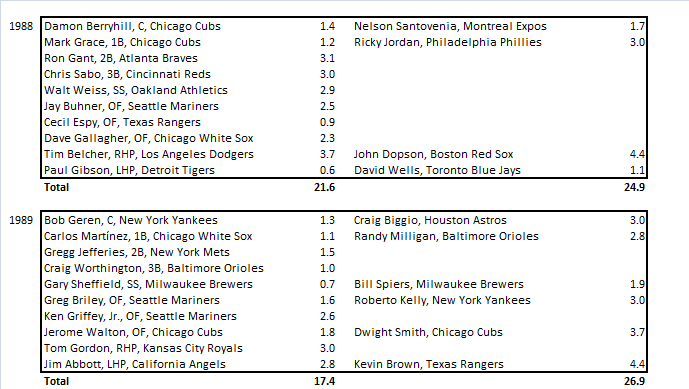

Even by traditional measurement, it’s hard to understand how Craig Biggio got passed over for Geren: east coast bias? There’s no way Kevin Brown was going to get selected over Jim Abbott. Topps usually avoids hype for its All-Rookie teams, saving that for its Future Stars brand, but Gary Sheffield over his own teammate is a clear bone for the investors.

The Frank Thomas omission is a really odd one – Thomas was already a huge name in both real baseball and in the price guides. One could only imagine folks falling in love with Morris’s empty batting average, or that razor jawline. Otherwise we’re getting into a collection of names you probably don’t remember being slightly better than other names you probably don’t remember. Which pretty much summed up the baseball card industry by 1992. And this article, really.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now