In Medieval times, your church was just a drafty hunk of stone without some good compelling holy relics. Bigger, better churches had bigger, better reliquaries. These objects were prized relative to their imagined power: Pieces of the True Cross or Jesus’s baby teeth, for example, would have significantly higher desirability than, say, a bone fragment from St. Blaise (patron saint against edema!). Similarly, relics from saints who performed miracles nearby or hailed from the same town as the church were especially valued, much as the people of Lewiston, Maine, might value Bert Roberge a little bit extra. The value of a relic comes from its proximity to the divine, a conduit from the sacred to the profane; possessing a relic can mean possessing a little bit of divinity itself. For this reason, they’ve frequently been the target of theft or destruction throughout history (to say nothing of the value of the containers, or reliquaries, in which they were housed, usually crafted from gold and inlaid with jewels or richly lacquered).

Most every baseball fan has a reliquary of their own, be it bobbleheads or autographed balls or actual baseball cards labeled “relics”: a fingernail-sized swath of a uniform worn by Derek Jeter, a sliver from a bat once held in the hands of Chipper Jones, a few threads from a jacket Babe Ruth once wore. Some reliquaries are more personal than others, honoring the hometown hero; some are orchestral in scope, celebrating the greats of the game. Either way, we put these things on our desks, small reminders during the workday of the bigger, better world of baseball awaiting us.

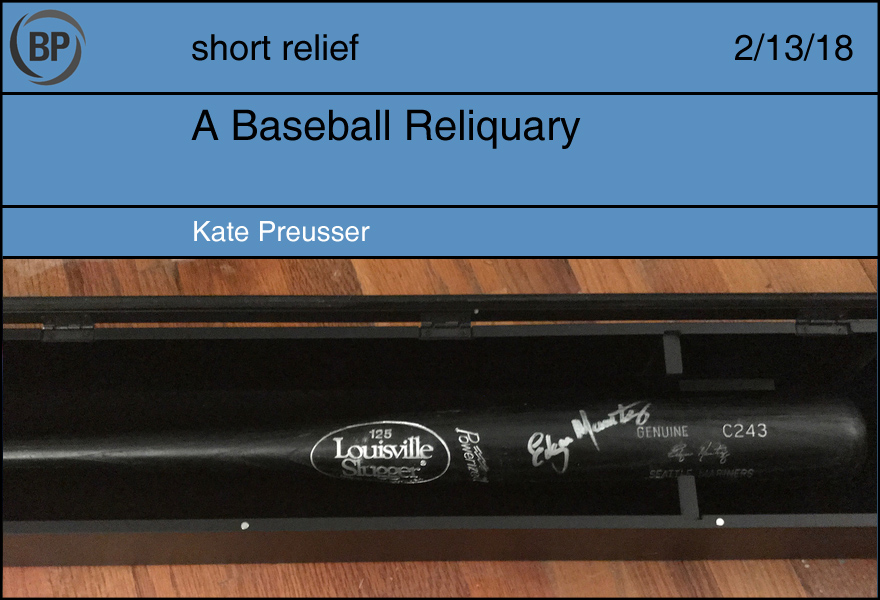

My own reliquary is typical of the smaller parish known as Mariners fandom–cards of my favorite players, a signed lineup card from the 2017 Modesto Nuts, a rotating cast of selected Mariners giveaways from the past year. But my most precious object won’t fit into my small desk-centric reliquary: a game-used Edgar Martinez bat. Occasionally I like to take it out and trace the silvered Louisiana Slugger logo, run my fingers over the complicated Braille of the wood grain, look at the spots where you could see he’d barrelled one up, powder-light halos on the black bat. (One day I will find a hyper-sensitive scale and see if it matches up with Edgar’s famously stringent measurements for what bats he’d deem acceptable, and try to figure out if the bat I have truly saw game action or was relegated to batting practice for being an eighth of an ounce underweight.)

That bat is one of the only things I ever truly, desperately wanted as a child; it had been donated to my school’s annual auction by the Mariners’ PA announcer, whose children attended the school. I remember crying when my parents brought it home, like the man himself was standing in front of me. I couldn’t believe it: an object my favorite player in the world had touched was in my house, leaning against the same wall where I took Christmas card photos and marked my height on the doorframe. I couldn’t stop staring at it. Eventually my dad tucked it away into a closet, fearful of thieves as a medieval priest. But I was content with just knowing it was there, in the house where I lived, the same air enhaloing both of us.

In late June of 2010, Miguel Tejada ended the longest home run drought of his career to date with a seventh-inning Camden Yards special that just cleared the left-center field wall. It came off a Marlins reliever named James Houser, who was making his big-league debut. He was 25. Houser pitched 1 1/3 innings and allowed three runs, all on Tejada’s homer. He never pitched in the majors again. His career ERA is 20.25.

The previous season, 2009, Houser reached Triple-A for the first time, as a starter in the Rays organization. Early returns were decent, but they owed substantially to an uncanny ability to induce double plays at critical moments and screaming line drives hit right at infielders. His fastball seldom topped 86 miles an hour; he had an okay changeup and curve. He nibbled, racked up high pitch counts and seldom lasted past the fifth inning. By midseason he led the International League in walks and had more of them than strikeouts. Everything about him seemed tentative and overmatched, on and off the mound. He was flummoxed by standard interview questions: “What do you want me to say?” he almost pleaded, softly, helplessly. In July, he radically changed his delivery, then changed it back. At the end of the month, he was released.

It was a glum end to propitious beginnings. In 2003, as a senior at Sarasota High, Houser was Florida’s “Mr. Baseball.” He grew up a Devil Rays fan and they drafted him in the second round with a $900,000 signing bonus. He was a tall, slender but projectable lefthander who rose steadily through the minors, but in August of 2007 he tested positive for PEDs; at the time, he was one of the highest-profile prospects ever caught. According to Baseball America, which ranked Houser 18th among Rays prospects before 2008, the Rays argued that he’d treated a heart condition with an amphetamine that caused the positive test result. It sounded fishy. He served the suspension.

The heart condition wasn’t a fiction. After his 2010 season, he had open heart surgery to replace his aorta and missed all of 2011. “I’ve got a wife and two kids,” he told an interviewer three years later, “so baseball was really the last thing we were thinking about when going into a procedure like that.” But he came back. Houser pitched in the independent Atlantic League for two seasons; in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Taiwan. He made it back to affiliated baseball in 2014, when he had five appearances for the Rockies’ Triple-A team.

In 2015, Houser became Varsity Assistant Pitching Coach with IMG Academy in Bradenton, right near his Sarasota hometown. “James comes from a rich background of baseball experiences,” according to his bio: Player of the Year, big leaguer. Think of what it doesn’t say—pitching around the world, heart surgery survivor—and it doesn’t look tentative at all. It looks like a baseball life.

(photo credit: © Troy Taormina-USA TODAY Sports)

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: there’s an MLB pitcher on the comeback trail.

I know, you’ve just spit out all the coffee in your mouth from the “There’s No Collusion in Baseball” mug that you got last November and insist on using despite everyone growing more and more uncomfortable with said mug as the days go by. But it’s true. Like the Bartolo Colons before him and hopefully less like the Mark Mulders before him, Tim “The Freak” Lincecum is planning a come “The Freak” back.

I think there are two immediate reactions one can have to the prospective return of the dude who last spent time in the majors getting beaten to death by the Champion Houston Astros’ early evolution in 2016:

1. Excitement over the return of a beloved fan favorite character of baseball lore and

2. Fury that teams are considering a longshot like Lincecum over stalwarts like Jake Arrieta or Lance Lynn who do not have to overcome the minor hiccup of “being 33 years old and three years removed from fifth starter numbers.”

And I think both are totally reasonable reactions! You can even be rooting for Lincecum while being pretty annoyed at MLB’s sudden transformation into the guy from college who just took his first stats class and won’t shut up about “inefficiency.” How do we split this difference and hold the two ideas in our mind at the same time you ask? Fan compartmentalization.

Fan compartmentalization is a concept that has been dulled by the recent value-obsession in sports generally and MLB specifically. It has a bit of the crotchety sportswriter to it, so it should be taken with several grains of salt, but the basic idea is simple. Effectively, it goes, you can be pretty excited about your baseball team making serious, sure-fire moves like signing JD Martinez or trading for Giancarlo Stanton — that’s the “Nintendo under the tree” moment in baseball fandom. But your Tim Lincecums, those are the unexpected books that your parents buy in a rush while checking out that become your favorite cult classic twenty years down the line.

The big names should sign, and they should get good money for their talent: I’d never debate that. It’s just that the big names have never really been the stories of the fun World Series teams we remember. They’re probably the biggest reasons the fun World Series teams win it all or are in a position to do it, but the human mind remembers the exceptional most of all, and the Ryan Vogelsongs or Albert Almoras or Marwin Gonzalezes stick out in our mind because they were never really expected to do what they did.

The truth is that collusion is almost certainly happening in baseball, and that’s a tragic thing for a beautiful sport. Because in an ideal world the Lincecum comeback story would be able to be enjoyed for what it is: the first glimpse at a potentially joyous narrative for the 2018 season. And there’s really nothing that makes the upcoming season more real than that.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now