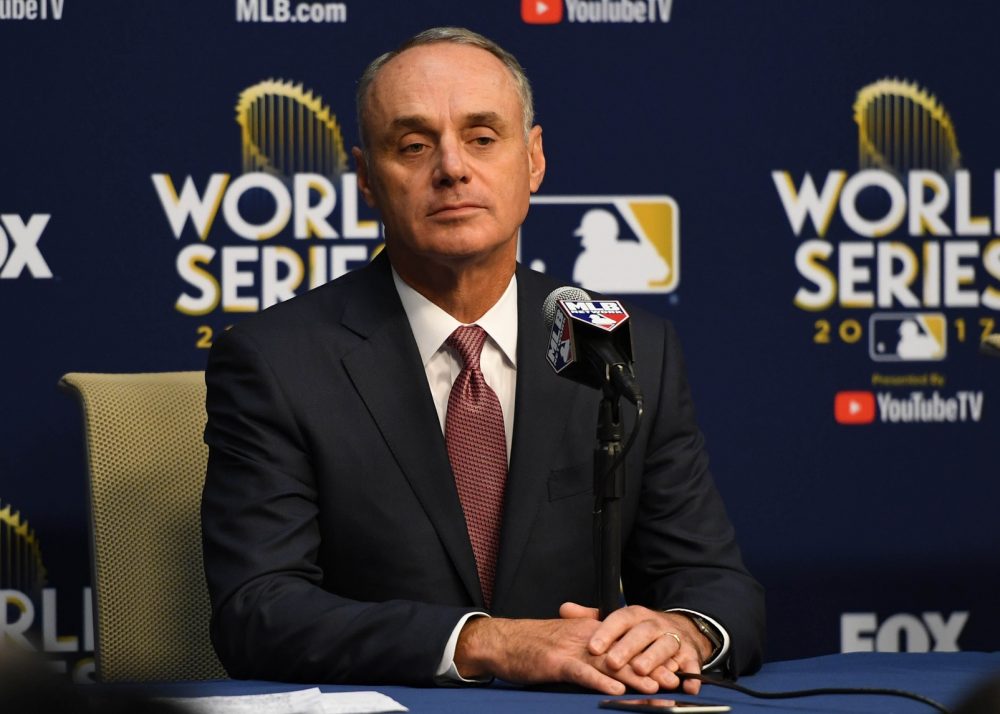

Rob Manfred was having none of Tony Clark‘s suggestion that MLB owners have been acting in poor faith in the free agent market. “It is the responsibility of players’ agents to value their clients in a constantly changing free agent market based on factors such as positional demand, advanced analytics, and the impact of the new Basic Agreement,” Manfred shot back in a statement last week. “To lay responsibility on the clubs for the failure of some agents to accurately assess the market is unfair, unwarranted, and inflammatory.”

In not so few words, Manfred is saying this season’s cold stove is just smart business. If players like Cy Young award-winning right-hander Jake Arrieta and All-Star slugger J.D. Martinez think they deserve five-year, nine-figure contracts, they have simply misread the market.

It’s certainly true that a number of long-term, big-money contracts for free agents over 30 years old have been catastrophic. It’s also true that the analytics movement that has been decrying such moves for over a decade has become entrenched in front offices across Major League Baseball. It might be true that avoiding the Martinezes and Arrietas of the world is the prudent business decision. None of that precludes collusion.

As Marvin Miller recalls in his autobiography, A Whole Different Ball Game:

“For a long time, even though the collusion was obvious, most of the sporting press and the media at large ignored it, or approved of it, or pretended that it was simply an allegation of the Players Association not supported by the evidence.”

Indeed, a glance at available newspaper records from the late 1980s reveals articles that at best refuse to take sides in an effort to retain an appearance at objectivity and at worst contain outright praise for the intelligence and frugality of the collusion plan.

Easily the most egregious of these was Daniel Okrent’s April 1989 article in Sports Illustrated, which praised commissioner Peter Ueberroth for his willingness to do whatever it took to drag baseball out of a “desperate spot” in the mid-1980s. “Someday they’ll write cases about him at the Harvard Business School,” Okrent wrote. “About the businessman who took on a new job in a new field, tamed the raging egos of his 26 bosses, turned his industry’s losses into unexpected prosperity and did it all while keeping his public image shining as bright as a new penny.”

Okrent was writing before the Collusion III case, but well after the owners had lost arbitration in both Collusion I and II. Ueberroth did not just happen to be commissioner during the time of collusion. He orchestrated it. And for years, Ueberroth’s legacy was as baseball’s financial savior, in large part because he was able to convince baseball’s owners—particularly its big spenders like George Steinbrenner—to engage in this scheme. Owners shared information about offers and as such were able to act in concert to prevent contracts of longer than three years, and they brazenly continued to do so even as the first two collusion cases were brought and subsequently won by the Players Association.

Okrent does eventually acknowledge Ueberroth’s role in the scheme:

“There are two singular blots on Ueberroth’s record, and the mention of either of them makes him bristle. Not only does he not accept blame for the charges of collusion by the owners (confirmed by two arbitrators), he does not even acknowledge that collusion took place—a stance worthy of the Flat Earth Society.”

None of this, though, impacts Okrent’s conclusion that Ueberroth’s legacy as commissioner is as a brilliant, business savvy man who saved baseball from financial ruin.

I find it frankly amazing looking back. Despite the evidence and arbitrators’ rulings showing the blatant reality of the owners’ collusion, baseball writers of that day were either unwilling or unable to call it what it was: the economic exploitation of the entirety of baseball’s labor pool, with losses trickling down from baseball’s richest free agents to its replacement-level journeymen and throughout the minor leagues as well.

It’s also amazing how similar public statements from the ownership side in the late 1980s are to Manfred’s statement from last week. “If they’re good players, we’ll take them,” Rangers owner Eddie Chiles told the Associated Press in 1987. “They’re probably pricing themselves out of the market.”

That same year, Barry Rona, head of the owners’ Player Relations Committee, told reporters: “There is always an open market. The fact that there is no bid on a particular player does not indicate that it’s not an open market.”

Of course, these similarities alone are not enough to prove collusion is occurring now. But we are human beings with critical thinking skills, and the connections here are not difficult to make. Even if actionable collusion isn’t occurring, free agents in 2018 are facing a historically stifled market.

When we call what is going on in this year’s free agent market “smart business,” we are making the same mistake baseball writers were in the late 1980s. They were valuing the short-term financial health of baseball’s owners over the long-term health of the game, its fans, and its players. The collusion of the 1980s may have led to immediate savings for the owners, but beyond the $280 million in arbitration rewards they wound up owing the players, their collusion also directly led to the 1994 strike, which dealt irreparable damage to the game and may have been a fatal blow had it not been for the home run explosion of the late 1990s.

And it also ignores that an active, healthy free agent market has historically produced fantastic and compelling baseball. “What happened with free agency turned out to be exactly the opposite of what the owners said,” Miller wrote in A Whole New Ball Game. “Teams could no longer stockpile talent, perennial cellar dwellers could improve themselves. Competition became keener, pennant races became more exciting, attendance increased, TV revenues went up, players were finally rewarded as the professionals they were, and everyone was happy. Everyone, that is, except the owners.”

Whether it is the result of collusion or mere stinginess, the owners’ current allergic approach to the free agent market threatens to create the exact opposite of the vibrant, dynamic league Miller describes above. And if you value “smart business” over the economic rights of the players and the entertainment of the fans, it might just say more about your priorities than anything else.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Agents and the union may not like it, but it's a direct outcome of the CBA.

In the end, all this article has to stand on per the current labor market is smug triumphalism ("But we are human beings with critical thinking skills, and the connections here are not difficult to make") and guilt by association ("And if you value “smart business” over the economic rights of the players and the entertainment of the fans, it might just say more about your priorities than anything else.") I get more and more disappointed with this iteration of Baseball Prospectus every day. "Critical thinking", my ass.

Otherwise, this is all speculation, and I'm not interested.