In the spring of 1896, a fifteen-year-old pitching phenom named Johnny Noonan was set to make his professional debut for the Brooklyn Flying Dutchmen. His manager hoped he would not only improve the team but, in doing so, help legitimize the fledgling, and faltering, Continental League. But during his first exhibition game, Noonan took a line drive to the head and fell into a coma. When he woke up, it was a hundred years later.

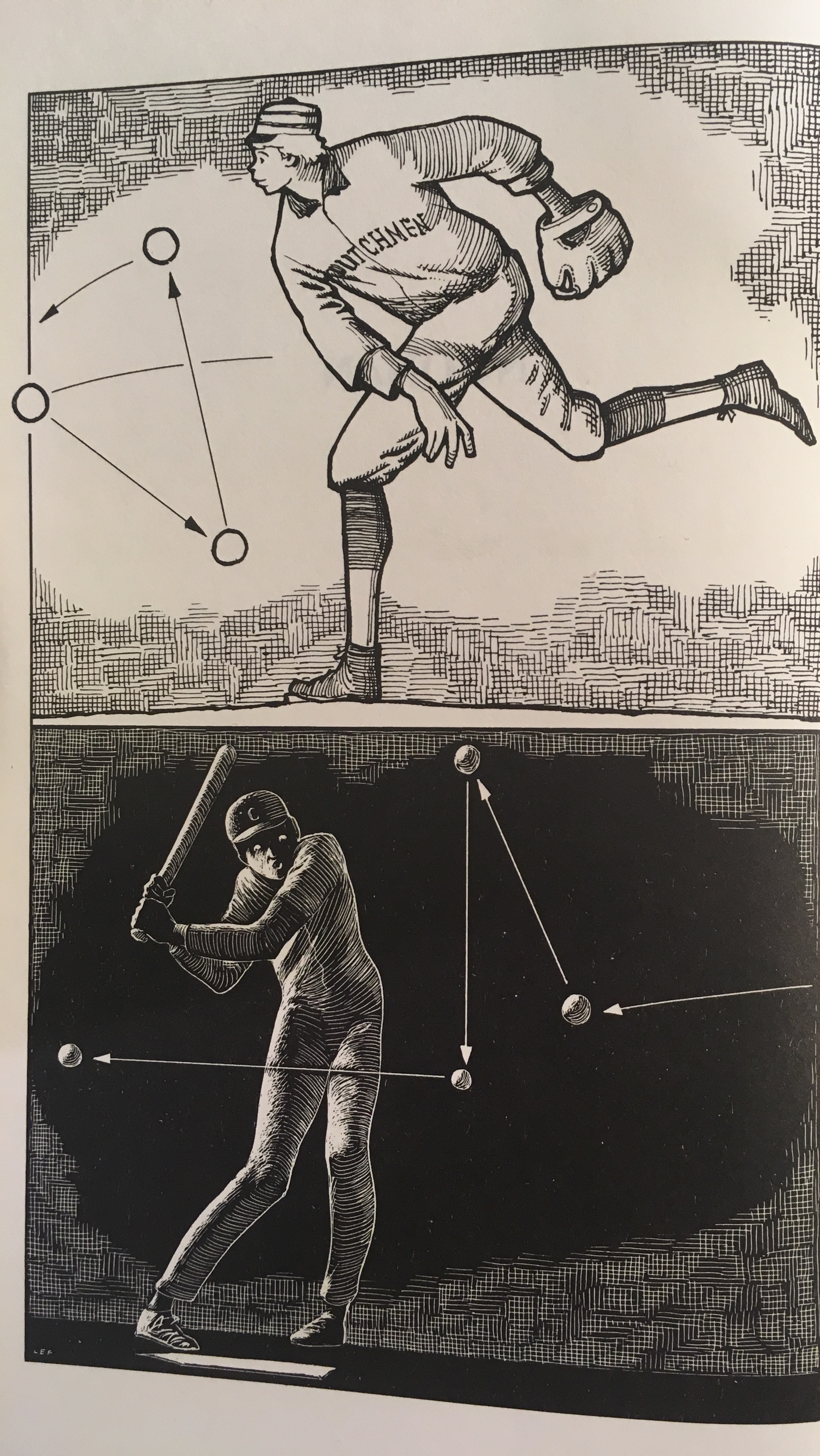

Oddly, that didn’t surprise him, but this did: he suddenly found himself with psychokinetic powers; he could will the ball to move anywhere he wanted. Soon Noonan was zigzagging impossible breaking balls over and around bats, and throwing not Bugs Bunny but Wile E. Coyote changeups that stopped dead in midair before plummeting to the ground under hitters’ futile swings. Noonan signed with the Mets, who kept the kid a secret (as they’d tried to do a decade earlier with Sidd Finch) until the World Series, in which Noonan achieved 81-pitch perfection—twice—and led the Mets to the championship.

Leonard Everett Fisher’s illustrated novel Noonan was published in 1978, during a decade plagued by oil shortages: lines around the block to buy gasoline, lengthened by the Iran hostage crisis. The book’s route from there to 1996 goes by way of the planet running out of oil in 1983. After a period of civilization-threatening panic, during which the US turns soot-black from burning through all its coal (our current leadership, take note), solar and atomic energy are fully harnessed.

But not all is well: “Life had become a humming bore. The whole country was enveloped in a monotonous drone of automation […] It produced a numbing effect. People would rather watch television and sleep than do anything else. And baseball, the national pastime, became the tedious symbol of the new malaise.”

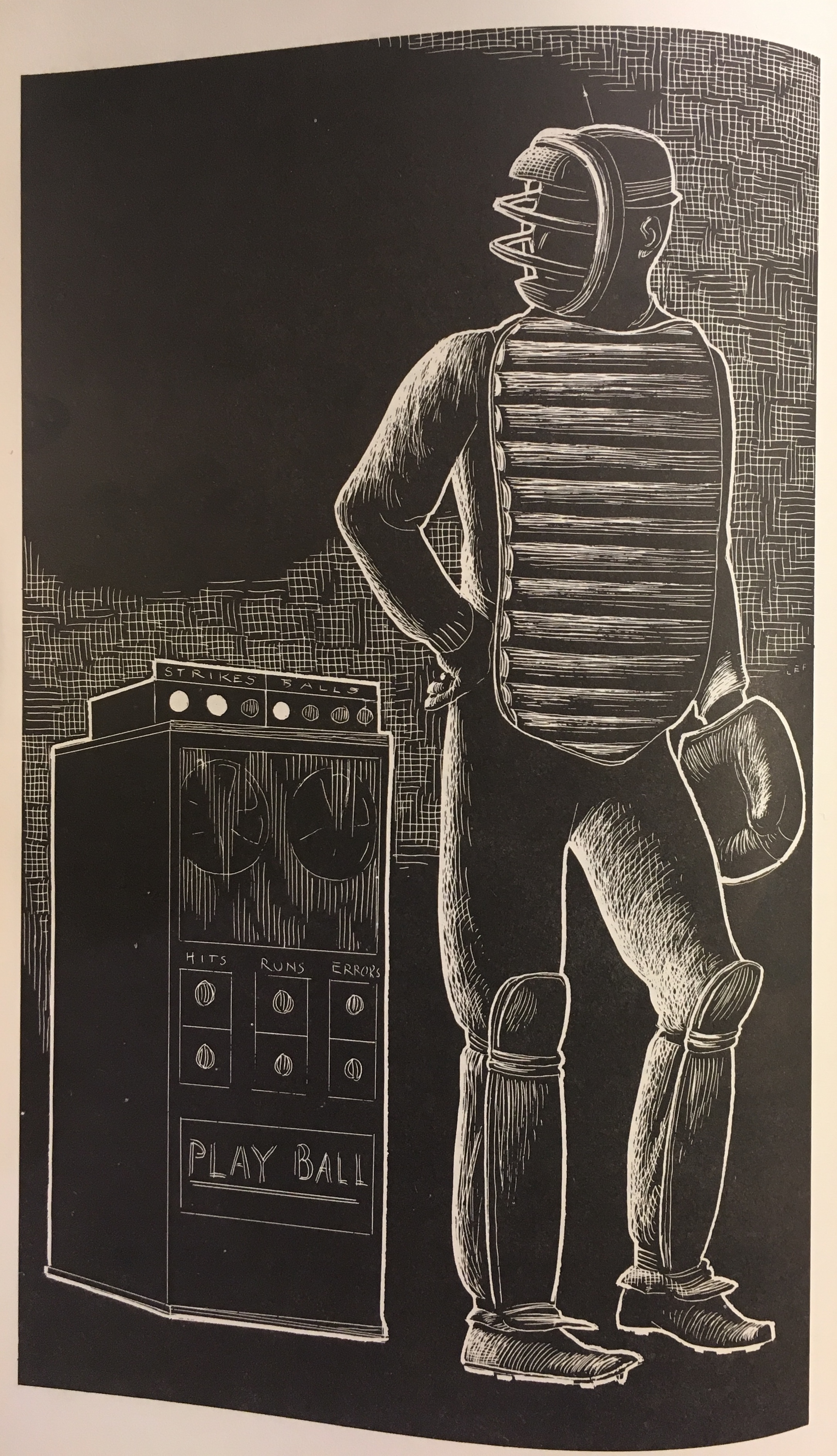

In Noonan, baseball survives the end of oil by contracting and consolidating into a single National League. Ballparks have been converted into “ballstudios.” No fans may attend games, and there are no umpires. Instead, “scanning devices and other sensitive electronic gear determined the outcome of every play, fed into a central computer behind home plate.” A human “tech-ump” (or “chump,” colloquially) “sat at his own computer console, which included an instant replay device.” Every single play is followed by a ten-second review, during which there’s a TV ad.

On the bright side, the worldwide effort to develop alternative energy has led to a truly international game: including ballplayers from “Russia, India, Italy, France, Indonesia”—even Iceland. Baseball has, in turn, aided diplomacy in the Middle East. Still, undercover US agents are planted on rosters “to keep tabs on the foreign athletes in the event that some of them were spies.”

Noonan is a short novel, intended for young readers, but it’s more complex than it may seem. Out of the apocalyptic crisis it envisions comes a sort of utopia, which in turn breeds a new dystopia, and the national pastime has, like any great institution, both changed and changed with the times: It helps beget a new world order and then corrodes inside it. And the novel connects the problems of both the future and the past, real and imagined, using the volatile material of the present in which it was written. There’s quite a lot going on in it.

“It took me three days to write that book,” says its author. Leonard Everett Fisher is ninety-three. His long, venerable career as an artist and designer includes the designs for a number of US postage stamps. He has also illustrated 250 books, dozens of which he wrote himself. He lives in Connecticut and is still active in the arts, currently serving on the board of the Westport Arts Center.

Fisher grew up in Brooklyn, a sandlot player and Dodgers fan. “When they moved, I hated them,” he says. “So I became a Mets fan, rooting for the guys who were always in last place.” (In Noonan, the Mets’ director of player development in 1996 is Ed Kranepool.) “I always thought about doing something about my love for baseball,” he says of the genesis of the book. Thomas Aylesworth, Fisher’s editor at the time (with Doubleday, as chance would have it), was an author of baseball books for young readers himself, and he encouraged Fisher to write one of his own. “So I sat down and wrote this fantasy.”

Like many fantasies, Noonan was assembled from elements of reality: not just the global oil problems of its decade of composition but, before that, Fisher’s study of geology and cartography in college. Drawing synclines and anticlines, Fisher got the notion that the earth might someday stop yielding oil. The 1970s were also the basebrawl era, partly driven by “controversy at the plate—in other words bad calls,” Fisher says. He anticipated “the human element taken over by computers,” and he isn’t surprised by the advent of instant replay and technologies like Statcast. “You could see it coming,” he says.

Noonan includes autobiography, too. “I grew up in an oceanfront house in Brooklyn, and we used to sail shells into the water to see if we could get them to bounce,” Fisher remembers. That detail pops up in the novel. When Fisher was seventeen, he collided with another outfielder in a sandlot game and nearly lost an eye. A baseball head injury; altered perception: “These experiences sat with me, and crept into what I considered to be the glue of the American people. If you look around the stands, you see every color in the rainbow.”

In Noonan, Fisher’s foresight of an increasingly corporate and technology-driven national pastime is thematically linked to poignant remorse over the past. The Flying Dutchmen of 1896 were not only going to help the Continental League challenge the National League; they were also formed to strengthen Brooklyn’s metropolitan identity and help resist annexation by greater New York. Among numerous real-life figures in Noonan is the reform-minded Seth Low, variously the Mayor of both Brooklyn and New York City (and President of Columbia University) who “embraced arbitration as a suitable labor-management negotiation tactic.” Low’s supporters in the book, including the philanthropist who bankrolls the Flying Dutchmen, hope to help make him President of the United States. (In Noonan’s 1996, Pete Rose is manager of the Yankees.)

We know now, of course, about the historical fates of Brooklyn and Seth Low (and Pete Rose), and about the deepening perils of our oil dependency. A certain sadness hangs over Noonan, but Johnny’s psychokinesis gives the book a ballistic, unpredictable energy that reflects the improvisatory speed of its creation. Reading it, you get the feeling that anything is possible. “Johnny’s perfect game was a metaphor for hope,” Fisher says. “I have children and grandchildren, and I worry about the kind of world we’re leaving for them. I’m an optimist. I may be a damned fool, but I’m an optimist so far as our world is concerned. Somehow or other we seem to come around, and I believe we’ll come around again.”

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now