In my Catholic high school religion class they taught us the value of seeing perspective from different angles; specifically the teacher talked about looking “at the light” as opposed to “in the light.” This was meant to be interpreted as, don’t mock someone for their beliefs unless you can empathize from a perspective of believing something yourself.

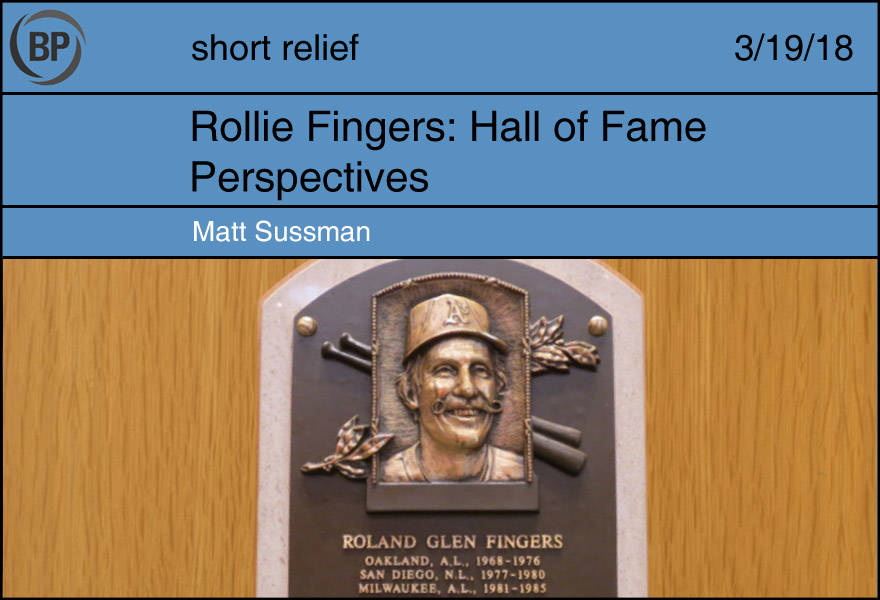

I believe Rollie Fingers is a Hall of Famer inasmuch as I know his plaque exists. And while I haven’t been to Cooperstown, I have no reason to doubt the evidence in front of me. In fact, the Baseball Hall of Fame website has 3D models of the plaques. So you can just scroll around and see it in all its computer-animated glory. Each scroll and twist gives you extra layers of insight on the man and what he means to himself and to the game.

From this perspective, suddenly he just looks like another tchotchke on the wall; his entire career of toil, sweat and sacrifice, boiled down to a few engraved sentences. Was it all worth it? Probably; I’m sure he has loads of memories pitching for the A’s and [squint] San Diego and Milwaukee? Didn’t know that. Swore he was with the Yankees at some point, too.

Typically you can spot a baseball player from a mile away, provided they are wearing their jersey and hat. But especially the hat. Baseball players sure look weird without them; they sink into normality when all you have is their face. It’s pretty clear that if baseball didn’t exist, Rollie Fingers would not be a Hall of Famer and this would just be a picture of Roland Fingers, That Dude From Down The Road Who Sold Watches.

Now view the plaque from the perspective from all players potentially being 30 feet tall and it was only safe to view their accomplishments through plaques, for fear of being trampled at the ballpark. Another way to look at it was that perhaps the players were all normal sized but the engraver was giant. Either way, both are good arguments for having fewer players in, for the sake of our natural resources.

But if you want the most awe-inspiring perspective of all? Imagine that you were devoured whole by Rollie Fingers and had to spend your last waking moments looking at the inverse of his face until the digestive process began. Think he’s still a Hall of Famer? Heavens no, he just ate you whole. That’s why there’s a character clause.

The 2018 professional baseball season is the first one since 1980 that won’t include Juan Samuel in some capacity. In 1980, at nineteen years old, Samuel began his MLB journey in the Phillies’ minor league system, and after an eighteen-year playing career with seven teams, he turned to coaching immediately. In the majors, he coached third and first base for the Tigers and Orioles and briefly served as the Orioles interim manager in 2010. Following the season in which Buck Showalter was named manager in Baltimore, Samuel joined the Phillies’ organization, where he was a staple on the baselines for seven years.

Samuel interviewed for the Phillies’ managerial vacancy at the conclusion of the 2017 season—as he did at the end of 2015, when the Phillies ended their season with Pete Mackanin in the interim role—but both times the Phillies chose another candidate: first Mackanin in 2015, and then Mackanin’s replacement, Gabe Kapler, in 2017.

It seems strange to say that I’ll miss seeing a base coach, a former player whose actual playing career I don’t think I remember, not first-hand. When Samuel was a Phillie on the field, I was a kid living in a place where it wasn’t really possible to watch the games, anyway, but Juan Samuel has literally been in baseball my entire life, and the bulk of that time he spent in Philadelphia. He’s atmospheric.

Samuel was also with me in baseball during a strange and difficult year. In 2006, Samuel managed the Mets’ AA franchise, the Binghamton Mets, to a 70-70 record, a team that was in the playoff hunt until the final day of the season. In 2006, I lived in Binghamton, one year into a Ph.D. program, and what I remember of that summer, beyond the stretching days off-campus that served mostly to remind me how far out of my depth I was, is the rain. By the end of June, rivers from upstate New York to Virginia flooded, and in Binghamton and neighboring Conklin, people said they’d never seen anything like it. It was one of the worst flooding events in the United States since Hurricane Katrina, but there was no hurricane. It only rained—and kept raining. Bridges closed, roads buckled, houses floated from their foundations, and still it rained.

Baseball stuttered and jerked; the regularly scheduled AA games postponed and reconfigured into 7-inning double-headers were postponed again, and that was the least of anyone’s worries. The flooding took lives, took homes. My university offered emergency shelter in the events center. When the weather stabilized, the B-Mets organized fundraising for flood relief, offered free tickets for people affected.

Our little house on a hill had only to contend with groundwater springing up through the cracks of the basement floor. We mopped and bailed, destroyed a ShopVac but didn’t lose anything else. We didn’t go to any of those scheduled and rescheduled games. I worked my summer job at the local zoo, helping to clear the paths of debris, to fix the trenches the run-off gouged, to do whatever the real zookeepers needed me to do because I was one of the few who didn’t have to cross the river—impossible for a while—to get to work. At night, I read, trying to learn all the things it seemed like all my classmates already knew. When the zoo reopened, I sold tickets and stuffed animals and ice cream and read more when no one came to the booth, feeling like I was getting nowhere, like I would never get anywhere, like this field of study I loved could never really become home.

Across town, the B-Mets took the field again. When there were fireworks after games, the sound carried through our newly open windows. I could see the bright sparks, how fast they flashed, little pinwheels of light windmilling go, go.

It’s spring training, and baseball is in the air in two very specific and relatively geographically isolated parts of the country. As the product of an increasingly archaic culture where baseball is imbued with some sense of “purity” that you constantly yearn to return to, in escape of the increasingly harsh reality of your adult life, you wish you were there, watching those dang practice games, enjoying that sweet facsimile of what you really enjoy.

But $169 per night in a hotel, even when you use that sweet discount code that beat writer gave you while they were HAMMERED at your local dive bar for some reason on a Thursday at 1am? In this economy?

So instead all that is left are highlights of that hot, elite action from the best players in the world.

Someone made a mistake! And a costly (not actually, because this is all meaningless) one. If you’ve witnessed the precision of these elite players—which you haven’t because rental cars costs $50 or more per day and you basically need to prostrate yourself at the altar of capitalism to earn $40K per year with your graduate degree in liberal arts—you know how rare and precious witnessing these mistakes can be.

Elite plate discipline! The ability to discern where a rapidly arriving object will exactly land. It’s the most thrilling skill in sports and doesn’t lose a damn thing when you’re watching it from afar.

OK…getting less certain here. Situationally it’s important—except nothing is important, it’s March and every month is a fight to see if you can find ways to feed and clothe yourself while convincing at least the most immediate people around you that this life is not a humiliating failure—but truly, deeply and completely, nothing is more true in this dinger-stained game that there are a lot of friggin flyouts all the time. THEY’RE DOING AN INTERVIEW WHILE IT’S HAPPENING! AN INTERVIEW WITH THE OPPOSING T—the boys of summer! They’re back and that’s all that matters in that sweet moment when you smell the grass

grass

grass

grass

Grass.

Die in the grass.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now