A few years ago, Emma Span published an article here at Baseball Prospectus on the subject of baseball fanfiction, specifically all the many weird sex scenes and pairings that the genre offers. (Please read for the mention of the Kevin Millar/Keith Foulke/Jason Varitek threesome.) The sex is what people tend to focus on when they look at fanfiction; fair enough, as there tends to be an awful lot of it. There’s plenty of opportunity for this to be awkward or uncomfortable or simply bad in fanfiction that builds off existing fictional characters, but there’s infinitely more so in fanfic that builds off the lives of real people. A lack of privacy is the price of celebrity, sure, yet there’s something here that can seem far more brutally intimate than anything possible with standard real-world violations of private life.

But I get this sort of fanfiction. The internet has porn for everything, after all; I find it a little weird that there are so many people out there dedicated to writing about Madison Bumgarner and Buster Posey having sex, but the internet has lots of weird sex stuff, and really, this is hardly enough to register on that scale. It’s just a tiny subset of the incredibly vast category that is “unconventional horny online content.” It can be weird, but it’s a weird that makes sense. The fanfic that does not make sense to me is of a different, less popular sort. It’s the baseball fanfiction that has no sex at all: Matt Holliday getting ready to say goodbye to the Cardinals, Michael Brantley buying his teammates a pet goldfish, Yadier Molina helping Aledmys Diaz grieve after the death of Jose Fernandez, Kris Bryant performing an exorcism on Anthony Rizzo after he gets hit by a pitch.

It’s all very earnest and straightforward, which is precisely what makes it so weird to me. The sex-fiction is often only about the sex; the players involved and the stories around them are more or less incidental, and the whole thing is an exercise for the writer more than anyone else. But these platonic stories are only about the players. They require more care, and more attention to detail, and the motivation for writing them isn’t nearly so clear. These stories nearly always get fewer likes and comments than their sexier counterparts; there are fewer of the stories themselves, with fewer people writing them. But those people are dedicated, and so these stories keep coming, season after season, all sincere and uncomplicated in their innocence. The writing reads like an act of love—an unorthodox one, but still—and, really, it’s hard to think of any other inspiration that makes sense. I love you so much that I want to imagine more for you. I love you so much that I will create you myself.

It’s taking ownership of the players in a way that feels extreme, and yet—more extreme than drafting them for a team that does not exist in a league that does not exist? More extreme than picking apart the intricacies of their performance on a level beyond what they ever see themselves? There’s love, at least, in one of these.

There’s a ghost living in Andrelton Simmons’s glove.

Simmons fears it. He doesn’t understand it, can’t understand it. For weeks at a time, he hears none of the glove’s seductive whispers. But sometimes, it seems like he can’t shut it up.

“To the left…”

“The batter is getting around on this fastball…”

“Take Albert to the batting cage…”

“Feed me, Simmons.”

These outbursts from the leather that adorns his left hand trigger an odd compulsion within Simmons. He takes a step to the left. He moves deeper in the hole. He implores Albert to go in the batting cage, no really, there’s a no supernatural presence there, you just have to get in some good hacks, man. He stores a rubbed-down baseball in the glove overnight, only to find it gone in the morning. Sometimes he has no memory of completing these tasks at all, only to find himself being congratulated by teammates at the end of an inning, or being interviewed by a beat reporter in the clubhouse. Like the opposite of waking from a nightmare and finding oneself in the embrace of a soft bed.

And always, unwittingly, Simmons is rewarded. He snares a hot shot up the middle. He ranges to his right and makes a miraculous throw across the diamond. He prevents sure disaster from befalling his aging teammate. Conscious again, he finds his glove glowing, a faint blue-green aura emanating from it that seems to disappear if he stares directly at it.

Simmons obeys the glove because he’s scared to find out what happens if he doesn’t. So far, he hasn’t noticed any negative consequences. His health is good, his friends like him more than ever, his love life is, well—let’s say, satisfactory—and his stat line is robust. Until the whispers from the glove go silent again, Simmons is at its mercy.

But soon, the positive effects start to crop up in unexpected places. Crooked numbers hang from Simmons’s name in the box score; a long fly ball that he was certain would end up in the outfielder’s mitt winds up in the third row of left-field bleachers; Scioscia scoots him up in the order, seventh, sixth, fifth.

He digs into the batter’s box, coils himself up as he waits for the pitcher to enter his windup.

“Slider, off the plate outside.”

Was that his bat talking? He stares at the whittled ash in his hands, but it’s gone silent.

What the hell…

“Andrelton.”

Simmons stares as the pitcher brings the ball to his glove, setting both at his waist.

“You have done well. Next,” he can barely hear the whisper above the crowd. “Next, Albert Pujols must die.”

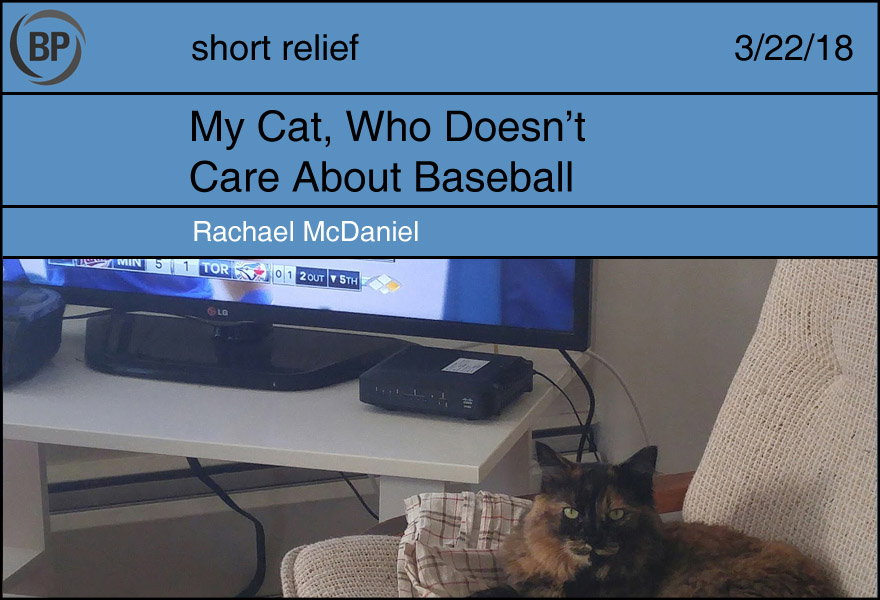

In early 2014, a time when I felt incredibly isolated and sick and unloved, I took a walk to my local SPCA in hopes of hanging out with a cat. I had grown up with a cat, a fluffy and irascible black cat named Tasha who would try to fight raccoons and slept beside my head at night to protect me from intruders. (I often woke up with a tail in my face, but I appreciated the sentiment nonetheless.) Tasha died when I was eight, and we didn’t get another cat, even though I always wanted to. At 16, though, I had reached a breaking point. I was desperate for any kind of connection with someone who wouldn’t hurt me.

I showed up at the SPCA, and immediately noticed something strange: there was a cat, a large tortoiseshell, in a room all by herself with no other cats. I walked over to the glass door of the room, where there was a note taped up. The note explained that the cat in this room had been at the SPCA for over two months without being adopted. “Give me a chance!” it said. The cat’s name was Dolce.

I looked down, and there she was, sitting right in front of me and staring up at me with wide eyes. She meowed so loudly that I could hear her through the door. I crouched down and kept meowing. The person at the desk noticed my interest. She told me that Dolce had to be in a room by herself because she didn’t get along with any of the other cats. She hadn’t been adopted because she didn’t get along with a lot of people. This only made me want to interact with her more. I asked if I could meet her, and was warned that she might hiss at me or try to take a swipe at me. I stepped into the room and took a seat on the chair, and to my shock and delight, she promptly leapt up to my lap and began purring. We both knew that we’d found a friend.

Dolce has been my friend for a few years now, through a lot of big changes in my life and a lot of nervous breakdowns. She puts up with some of my more annoying habits, and seems to understand what’s nonsensically important to me: While she loves to sharpen her claws on my desk chair, she never scratches the Troy Tulowitzki jersey that’s draped over it. She ducks underneath it like a little Blue Jays-themed ghost.

Dolce often sits with me as I watch baseball games. I get overexcited sometimes, yell at the screen or clap my hands, and she jumps up, offended by the noise. (Neither of us like loud noises much.) Sometimes she stares at the screen for extended periods of time, as though she’s watching the game, and sometimes she just sleeps.

I know that Dolce is a cat, and has no understanding or care for baseball or sports or anything like that. She has no reason to sit around with me and tolerate my annoying baseball-viewing behavior; she is free to come and go as she pleases, to roam around the neighborhood or find another room to sleep in. I am grateful that she chooses to spend time watching baseball with me instead. It’s nice to have a friend.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now