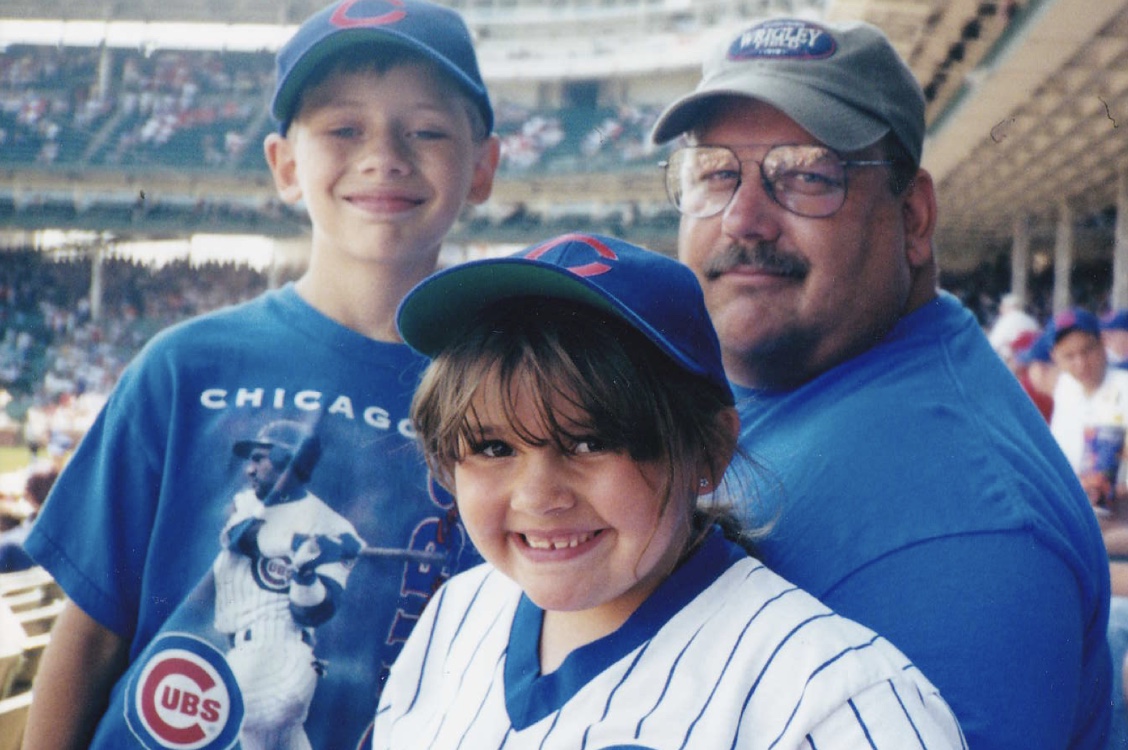

This is my first Opening Day without my dad. Not that Opening Day had been a ritual for us, or that it holds any particularly special meaning beyond our shared love of baseball. But my dad and I did share many of these ceremonial beginnings, mostly of the amateur kind as he coached my Little League and middle school baseball teams. Our first game with Dad as coach when I was 12, culminating in a championship. Our first year together with a brand new team in middle school, a team of misfits borne of his mind when the local league couldn’t support an in-house league. Many years of hope for the team residing at Wrigley Field, most years ending in disappointment. Now I enter my fourth season of covering Cubs baseball for BP Wrigleyville and my dad won’t be around to read my writing, or text me about a Willson Contreras homer, or joke about my grandma’s temperamental relationship with the Chicago National League Ball Club.

When the Cubs won the World Series two seasons ago, the relief and joy I experienced secondhand for my dad and my grandma reflected emotions that thousands (millions?) of others felt for their loved ones, living and gone. It was a unique event that invoked both the deeply personal and the broadly communal love that a shared fandom instills at its best. I had hoped that the Cubs would overcome that seemingly insurmountable obstacle before my grandma passed away. She had long since retired from coaching soccer and softball to kids in Berwyn, slowed down the avid baseball card collecting that we shared in my youth, but she still tuned in to watch the Cubs—provided they didn’t play past nine o’clock. Now 85, she’s outlived both of her sons, a cruel and unfair fact that resists interpretation but invites reflection. She taught my dad to play baseball, and they, in tandem, taught me: Dad serving as proper coach, Grandma tossing me grounders in the front yard and catching my pitches while seated on the swinging rocker with green seat padding, as I used an exposed maple tree root as a makeshift pitching rubber. The Moser family baseball lineage is a bit more fractured today than it was at the end of last baseball season. There’s a position missing, and free agency won’t fill it.

So I enter this season with you all once again, but a bit differently. The weight of my dad’s sudden passing just over a month ago still saddles me with a drooping and slouching depression that makes writing difficult. I won’t dwell, as I hate writing about myself, but the 2018 Chicago Cubs will offer me a respite from the anxious thoughts that rattle around my brain. A bit of spring after the longest winter to aid me in coping.

I’ve had kind of a weird month. As soon as it began I got horribly physically sick, and then horribly depressed while the physical sickness got worse, and then I had a play running while I became progressively more depressed and sick, and then, and then, and then. It all just kept going. Hours in doctors’ offices and ER waiting rooms, eye-avoiding smiles at opening-night parties. Going to school six hours every day, coming home, work into the early hours of the morning. I had this coming, I guess. My body was fed up with my constant abuse, the months of not-sleeping and stress. My brain was fried.

With all this going on, I didn’t have much of a chance to watch any spring training games. When I had a chance to catch up on baseball news, all of it was terrible, and everyone was angry. So I haven’t been excited for the season to start. I haven’t been excited about baseball, or about writing, which was seriously upsetting to me, maybe even more so than anything else. I felt like I’d ruined two of the only things that were consistently good for me; I felt like whatever stories I’d been telling, about baseball or about myself, were no longer useful or meaningful or true. My whole deal here, when it comes down to it, is a desire for connection. I like to think that’s the goal of sports fandom as a whole. But nothing felt like it was connecting anymore, and the more I strained to reach out, the more I felt alone.

So, as ridiculous as this sounds, I was ready to just quit. Delete my twitter account, stop answering my emails — what did any of it matter? None of you would ever know what had happened to me. I could throw my laptop in a trash can and find a quiet ditch to lie in. I could go on a long walk and never come back.

When I got home yesterday, after spending another exhausting day bouncing between crowded buses and classes and the hospital, my brother was watching the Jays play the last of their annual exhibition games in Montreal. It was the bottom of the ninth, and the score was still tied 0-0, and the crowd was thinner than it has been in recent years. I sat down, just for a moment, before I would have to get up and eat something and then start working again, letting the subdued game noise just kind of wash over me.

Vladimir Guerrero Jr. stepped up to the plate. He launched a curveball into the seats in center. And all of a sudden the crowd exploded, as if there were twice as many people than there actually were, and all of the Jays players flew off the bench screaming, and everyone online was screaming, too. Because it was a such a beautiful moment. Such a perfect story, a perfect circle connecting one generation of greatness to the next, a whole lot of people’s joy and hope all focusing itself on this one thing.

I remembered why this is so important to me. March is ending. I’m excited for the season to start.

I picked a terrible time to tamper with my meds; I should have stayed on familiar footing for the first day of the new season. Opening Day is one of my favorite days of the year, along with Jackie Robinson Day, the first day of games after the All-Star Break, the days with four division series games, my birthday when I get takeout and watch baseball all day, and pretty much any day that Max Scherzer starts.

Of course Opening Day will be a happy day all day long, but I may not be able to tell. I want to swoon with the sudden blossoming of the 2018 season, but I tampered with my meds and now I have the emotional capacity of a bog body. Bog bodies don’t swoon. Nor do they write concise and thoughtful things about baseball. Not even when there are so many cool things to discuss.

Besides, I’m getting older, and the long view teaches us that things which appear interesting now won’t matter all that much later on. I used to get so mad at the MLBPA that I would stop watching games in protest. The first time this happened was in 1993, when I read an article about a player who, on condition of anonymity, described his anxiety about steroid use. He didn’t want to take steroids, he said, but it was causing enormous pressure. Could he keep playing if he didn’t resort to them? He didn’t know. He sounded so alone.

Where’s the union when a guy needs one? I come from coal miners, and a heritage like that arrives ready-made with a pro-union attitude. I understand what unions are for. They are the collective voice of workers who need a way to protect themselves and advance their self-interest, a collective. In the setting of a coal mine, unions can mean the difference between life and death. I didn’t know if the long-term outcomes of steroid use involved life and death, but I thought the union should be protecting its members in matters of health and safety. I was, in a word, indignant. I ignored a lot of baseball in the 1990s, although I kept an eye on trends. You can’t completely ignore baseball. You might miss something!

Where was I? Oh yes, getting older. I still get angry with the Player’s Association, but I don’t get indignant and I don’t miss games. I’ve lived long enough to know that life is messy, that the good comes with the bad, and that the best approach to living is to stay engaged in case you miss something.

Engagement is harder than normal this week, what with being bogged down, but getting older also means that I know I’ll adjust. For now, I’m going to make popcorn, put nothing on it, and watch Max Scherzer pitch. Somebody swoon for me.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Short Relief has brought something special and different to BP, and I very much enjoy your work.