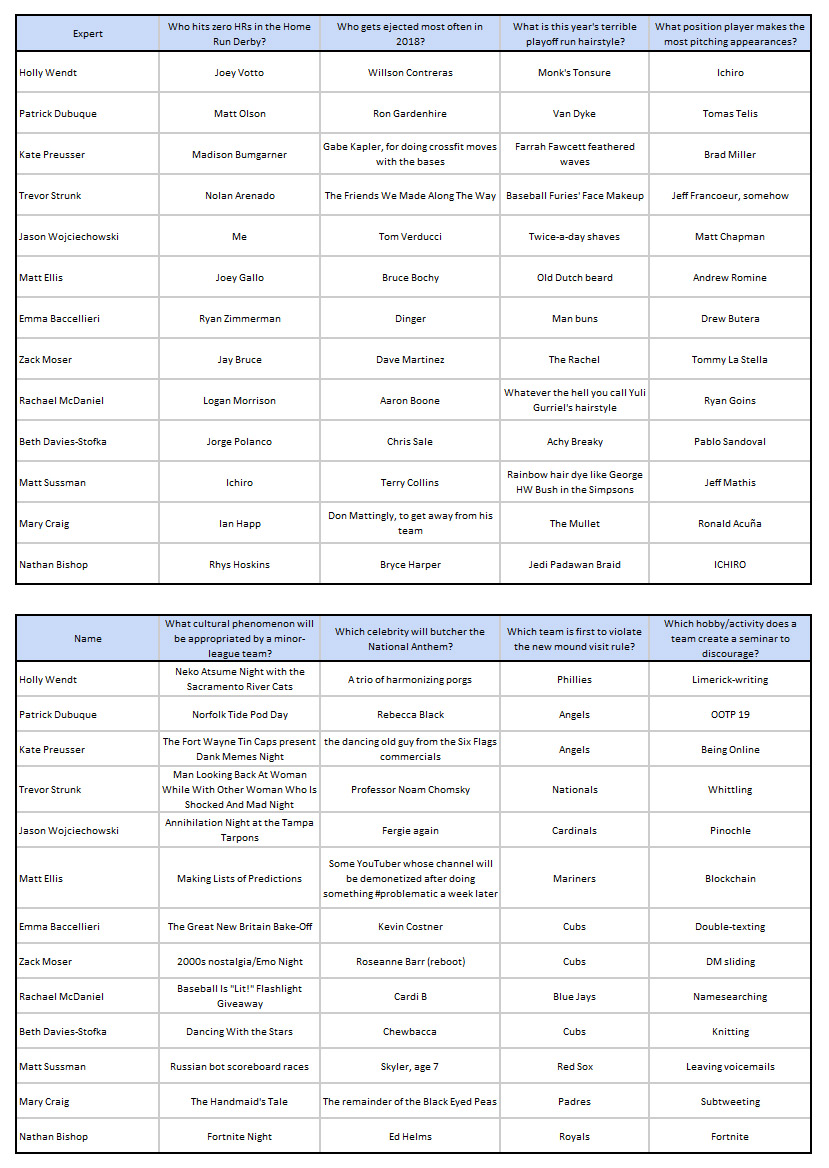

Yesterday the BP staff made their traditional predictions: standings, awards, victors. It’s a pleasant exercise, certainly, but you don’t come to Baseball Prospectus to learn generic information like “who will win.” You want the hard truth, and we here at Short Relief are there to provide. Said prognostications come in two flavors: answers for general questions, followed by a dozen examples of what will happen in Major League Baseball this year, recorded in excruciating detail.

Holly M. Wendt

On an otherwise perfect June evening, in the top of the second inning, clouds will tumble across the Philadelphia sky. The wind rippling the flags in center will shift, everything blowing in. From all parts of the air, the wind will blow in, tugging uniforms as if by small, agile hands. In center field, Odubel Herrera will feel the gilded tips of his braids skim back, then front. He will remember this feeling from 2015; he is one of the few who do, and he will remember the stories he heard about 2011, the ones Chase Utley told, head shaking. Chase Utley’s hair is now as gray as the squirrel that will appear from behind home plate. No one will have seen it arrive. The Phillies’ bench bats will hold their breaths, dread the skitter-claw sound it will make, the dark omen it brings. The Cardinals’ bench will laugh as the squirrel scurries across the grass, toward Aaron Nola’s birchbark legs.

At the edge of the mound’s velvet dirt, the squirrel will pause, the uncertain wind or some other force tossing its thick gray tail. Yadier Molina’s grin will stiffen and fade as the squirrel turns, faces the Cardinals’ dugout, and runs.

Matt Sussman

Cotton Candy Sales Will Plummet In Every Ballpark. Cotton candy is one of the happiest sounding treats in the world. It’s huge and it’s literally flavored sugar. But nobody finishes that whole thing without a large amount of regret. It’s bulky, it’s sticky, it looks like fiberglass insulation, and we’re collectively going to wake up and realize ice cream and chocolate are way better vehicles for sugar.

Trevor Strunk

At 5:47 PM, on June 17th, Bryce Harper will have a sudden realization that the world as he knows it consists of innumerable physical impulses, electronic bursts, and impossibly small minutiae that occur in the folds of his cerebral cortex daily. Recognizing that he has no control over any of these things, he briefly considers becoming a monk and retiring to the Scottish foothills to fully comprehend the mysteries of free will, the mind, and the divine. He doesn’t actually retire to a monastery or even buy tickets to Scotland, but he does pop out to shallow center during his first at-bat of his next game because he’s distracted by these concerns.

Rob Manfred will walk into his office one day this season — perhaps sometime in late May — and be unable to remember the name of the snack that he used to love as a child. The inability to recall the tasty treat, a kind of inversion of the Proustian Madeleine, will so distract Manfred that he will be unable to think of anything else all day. He will sign an order for a series of jerseys for some team called the Los Angeles Dourdgos; he will induct utilityman Omar Infante into the Hall of Fame; he will permanently ban triples. At the end of the day, he will purchase a bag of Bugles in a fit of desperation. They are not the snack he wanted, but they help him forget enough to go to sleep.

Kate Preusser

As much as baffled announcing teams try to hide it with talks of juiced balls, by the time the All-Star Break rolls around it’s clear: something is wrong with baseball’s aces. Sometime in late May, Stephen Strasburg starts gradually leaking home runs like oil on a 1993 Jeep Grand Cherokee. Corey Kluber’s ERA can drive. In June, Clayton Kershaw gives up seven runs in three innings to the Padres, and misses the rest of the season on the DL after he throws his back out throwing a helmet across the dugout in a blind fury. Max Scherzer stays up until the wee hours of the morning, watching film and drawing increasingly complex diagrams of the strike zone. By August he is sent to a home in Pennsylvania Dutch Country, where he is taught woodworking. If a baseball should land in the yard, it is swiftly disposed of.

Meanwhile, the hitters continue to hit. Game scores start to look like football scores, then basketball scores. Rob Manfred is dragged before a tribunal and made to account for his sins; he cannot. At first people are excited, but eventually they tire of the offensive onslaught. Children run out of space on their display shelves; the excess balls choke the gutters outside stadiums like dead leaves. Eventually, they stop coming to games at all, and with them their parents, but still, ceaselessly, the hitters continue to hit.

Rachael McDaniel

Sometime near the end of April, in the eighth inning of a game between teams that not man people really care about, a weird injury happens: Jogging to first on a routine ground ball to second, a player falls over as though he has tripped over a string. He twists his ankle and has to be helped off the field. It’s a pretty stupid-looking play, but the player himself doesn’t find it very funny. He insists that he genuinely was tripped — that, somehow, an almost invisible string had been stretched across his path.

Everyone, of course, writes this off as ridiculous baseball-player superstition, if not an indicator of a more serious break with reality on this player’s part. But a few weeks later, a carbon-copy of the injury happens to another player. Then another. Then another. All of them say that they were tripped. Some people start analyzing footage, claiming that, in every game where this injury occurs, a cloaked figure can be spotted in the stands along the first-base line. The figure always disappears after the injury.

In the middle of June, as suddenly as they began, the spate of phantom trippings stops. Still, they keep looking for the person in the cloak. They stay afraid.

Matt Ellis

By all accounts it’s going to be a pretty by-the-books year. Ground zero for this new blow-it-up-and-let-the-FAs-walk model, just about every division is booked, and the biggest upset could be a mediocre team sneaking into WC2 and then losing in the DS. With that in mind, here are my top two predictions for the 2018 MLB season:

1. The Padres Will Not Win The World Series. I know, I know–I’m a pessimist. But hear me out here: the NL West is pretty stacked with at least the Dodgers and the Diamondbacks looking like legitimate playoff material on paper. Eric Hosmer was quite the offseason get but, all things considered, I really think it’s possible that the San Diego Padres will spend October out on the links instead of gunning for that ring. I’m willing to hear your counterargument.

2. Alex Cora‘s Job Will Be Called For By A Prominent Boston Media Guy By June. No deep work on this one. Just please remember that I called it here first.

Patrick Dubuque

September 12: The ball is slicing, but James Caldwell watches it in as if it were happening in the past, leans over the rail and catches the foul with both hands. It is his first. His palms throb as he studies his new prize, and though the two older boys salivate in anticipation, he ignores them. “I have a three-year-old son at home,” he says to no one, and even if it isn’t enough, it’s enough. The game continues on; one team wins.

The ball sits on a shelf in the garage; he shows it to Brian when it seems like he’s ready, the scuffing of the impact, the fading imprint of Robert D. Manfred, Jr’s signature. Taylor Trammell hit this ball, he tells him, trying to give the thing life. But Taylor Trammell is already just another ballplayer, nothing more than a familiar name, and Brian only cares about comic books. Every so often, James picks the foul ball up, holds it in a circle change grip, savors the feeling of touching something that had touched baseball. His only foul ball. He could give it away, but then the story dies, then it becomes just another used baseball, the same as all the others. He puts his prize back on the shelf, and waits.

Beth Davies-Stofka

In 2018, everything will change. Rick Hahn, having noticed that American streets are packed with women, minorities and students, suggests a revised approach to broadcasting. His ideas are adopted on the spot. All games slated for WGN will be televised live in Spanish, and Univision Radio will be featured prominently on MLB.TV. Women are added to the broadcast booths and high school journalists are hired as on-field reporters. Games at Guaranteed Rate Field sell out as women, minorities and students welcome the team’s outreach and become loyal fans. Television and radio ratings soar. The new fans transform the park into a fun and safe place, and White Sox games become Chicago’s favorite family destination. By August, the average White Sox fan is 20 years old. Observing this demographic transformation, other teams quickly follow suit. Baseball’s marketing worries are over.

Mary Craig

As May turns into June, the air thickens with humidity and the sun rests higher in the sky. The games begin to matter more, so too do the off days, as routines become so established they border on unbearable. And so Matt Harvey decides to try something new today, June 7th: pancakes for breakfast. He’s never been good at flipping them, the form of the pancake remaining elusive. Until today of all days. Today, he decides to try flipping them with his left hand. Hesitantly at first, he slides his spatula under the bottom of the pancake, and with a sharp flick of the wrist, perfection. He tries another and another and another, all perfectly round. It turns out he is actually left-handed.

Nathan Bishop

The day will be August 21st, the place will be Miami. During a lazy Tuesday evening, baseball’s opposite ends of the economic and prestige spectrums will circle around, with one devouring the other, like a snake devouring itself.

The Yankees, of course, will be the ones baring their fangs, and the Marlins the whites of their bellies. The inning will be seven, and the sunset in Miami that night will be a very particularly bloody shade of red. In one half inning, both Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton will smash linedrives off the Marlins home run sculpture. As Stanton circle’s the bases, the sparse crowd will boo, sans Marlins Man (he will be at the White House to be right behind the President for a speech of extremely marginable importance).

The camera will find Derek Jeter in the owner’s box. Reggie Jackson will be sitting next to him. Both men will be laughing.

Emma Baccellieri

There’s no manager so known for both his creativity and his fixation on stretching the rules juuust as far as possible as Joe Maddon. Here, then, is how Maddon will try to get around the new mound visit rule: It is early June, and the Cubs are down by one in the fourth inning, with Jose Quintana on the mound. Maddon made his first visit out to Quintana after he loaded the bases the first time; now, one of those runners has come home, and there are two outs, and he wants one more visit. Just one. A few words. He thinks about banging something out in Morse code on the dugout railing, or miraculously securing the services of a carrier pigeon, or somehow willing Quintana to come over to him.

He grabs a piece of paper. A second later, it’s an airplane.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now