Blue Jays third baseman Josh Donaldson has a dead arm. But what does that mean?

Rumors that Donaldson had been dealing with throwing issues surfaced nationally on Opening Day, as he continually exhibited weakness in throwing across the diamond. His throws lacked the velocity and accuracy required to play third base.

As fans and media alike wondered what was going on, both Donaldson and manager John Gibbons sought to get out in front of the story by minimizing the injury, explaining that it was something they were aware of and have been treating since the start of spring training.

Gibbons told reporters that Donaldson’s arm “was hanging a bit” throughout the spring and that he’s dealing with a “dead arm.” Donaldson himself has stated that his shoulder is a non-issue. He has admitted that his shoulder feels “weak” and that if he doesn’t need to air throws out, he won’t. Furthermore, and possibly more importantly to the Blue Jays in 2018, Donaldson said that his shoulder weakness does not affect his hitting.

Dead arm is “any pathologic shoulder condition in which the thrower is unable to throw with pre-injury velocity and control because of a combination of pain and subjective unease in the shoulder.”

First, let’s look at the anatomy of the shoulder capsule and define terminology to better understand what’s happening. The shoulder girdle is made up of the scapula, clavicle, and humerus. The humeral head articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula and the two move together in rhythm during all motions of the arm. Ever seen someone have to shrug to lift their arm? Generally the cause is weakness in the rotator cuff muscles and a lack of mobility of the scapula. The scapula has to move with the arm for normal motion.

The two form the glenohumeral (GH) joint, a ball and socket joint, that is designed to move in all planes. The labrum surrounds the GH joint, providing increased depth and stability. Moreover, all joints are housed in a capsule that separates it from the rest of the body and provides fluid to the joint. Ligaments provide stability within the capsule.

The overhead thrower has developed osseous anatomical changes to their humerus over repeated use. Increased throwing leads to an increase in shoulder horizontal abduction and external rotation range of motion (ROM) compared to the non-throwing side. These anatomical changes to the humerus bone are called humeral retroversion. Greenberg, et. al describe the changes as follows:

Throwing athletes exhibit a more posteriorly oriented humeral head (humeral retrotorsion) in the dominant arm. This asymmetry is believed to represent an adaptive response to the stress of throwing that occurs during childhood.

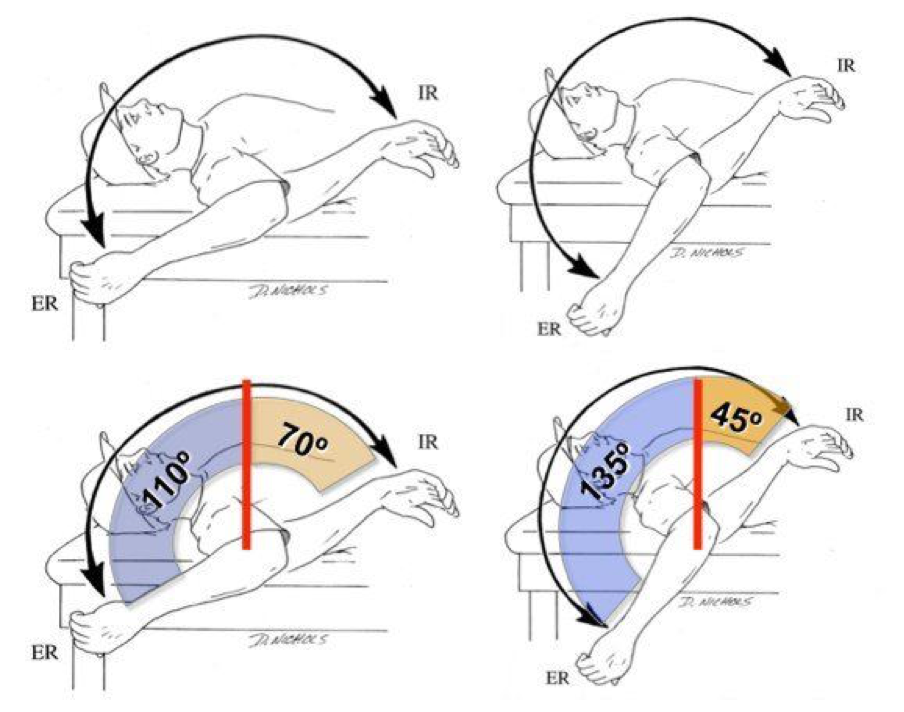

What this means is that as we grow up throwing, our humerus “twists” at the growth plate, allowing us to achieve more external rotation in the late cocking phase. This asymmetry in the throwing arm is normal. The bony changes are adaptive in nature and allow for an increase in external rotation (ER). And when we look at throwers, they will have more ER range of motion and decreased internal rotation (IR) range of motion compared to the non-throwing arm.

The main thing to notice is that the total arc of motion is unchanged—180 degrees of motion is normal. Many researchers have attributed the lack of internal rotation range of motion as problematic and the cause of dead arm syndrome. This theory does not account for humeral torsion and natural adaptations. Throwers need increased ER in order to generate velocity. However, increasing internal rotation ROM would increase the total arc of motion, causing the shoulder to become more unstable.

These IR ROM deficits have been identified as Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit (GIRD). GIRD is attributed to posteroinferior capsular tightness. Studies seem to ignore the bony changes to the humerus. They attribute the lack of IR as an abnormality and not an adaptation. The difference in ROM measurements is not due to soft tissue restriction, it is due to the bony adaptations we undergo as adolescents. I played baseball through high school and my fastball touched 73 miles per hour. However, 20 years later, I still have increased ER and decreased IR compared to my non-throwing arm.

Most likely, Donaldson’s dead arm is the result of weakness over his scapular stabilizers, malposition of his scapula, and tightness of his pectoral muscles. If his total arc of rotational motion is less than 180 degrees, rehab would entail stretching of his posteroinferior capsule. But what if it is something else? If GIRD is normal, then what is going on with dead arm? What is the worse-case scenario?

Repeated overuse of accelerating the arm in the late cocking phase can cause a superior labral lesion from anterior to posterior (SLAP). Arthroscopy of throwers diagnosed with SLAP lesions reveal a peel back phenomenon. In the late cocking phase, the bicep can cause a torsional force on the labrum. The “peel back” refers to a peeling of the superior labrum from the bone. Depending on the severity, SLAP lesions can be treated non-operatively through interventions designed to correct throwing biomechanics. Surgery for SLAP repair would effectively end Donaldson’s season. However, since his hitting would remain unaffected, I would surmise that he forgoes the operation while remaining in the lineup as the designated hitter.

What does that mean for Donaldson, the Blue Jays, and their fans? Treatment consists of stretching, strengthening (the Advanced Thrower’s Ten), plyometric drills, and an interval throwing program. What we can deduce based on the evidence is this: Dead arm is not something that you play through or tough out. Assuming the Blue Jays have performed an MRI, we can possibly assure ourselves that there is no labral tear or rotator cuff involvement. But we can never know for sure. Throwing injuries seem to pop up completely out of the blue.

Rehabilitation will improve position and control of the patient’s scapula. I haven’t seen a picture of Donaldson’s shirtless back, nor have I seen how his scapula moves and the position relative to the left scapula. Moreover, I don’t know what his total arc of rotational range of motion is. So without being able to assess him, let’s assume that his dead arm is due to scapular dyskinesis (faulty movement and malposition of the scapula) and weakness in the rotator cuff. This assumption is based on Donaldson’s description of symptoms and lack of pain.

The above therapeutic exercises and neuromuscular re-education should get him back on the field and at full strength. Based on reports that I’ve read, Donaldson and the Blue Jays’ medical staff have been treating his shoulder throughout the spring. Gibbons has stated that they expect Donaldson to play in the field “within the next couple of days.” Donaldson has said that he feels close to normal.

If I were his treating therapist—which, to be very clear, I am not—I would advocate rest. Hitting will not increase his symptoms, so Donaldson’s bat could and will remain in the lineup. Rehab consists of stretching and strengthening to improve scapular position and neuromuscular control while improving the biomechanics of his throwing motion. Rehab is patient dependent and does not necessarily have a timeline attached.

Beyond just the Blue Jays’ 2018 season, Donaldson is set to become a free agent after this year and will need to prove to teams that his arm is healthy in order to maximize his earning potential.

Jason Woodell is a licensed physical therapist assistant at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital Sports Medicine and the James A. Haley Department of Veteran Affairs in Tampa, Florida.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now