(after Updike, and Camus)

“Word is the actual attendance at Monday’s #Rays-#White Sox game—people who used tickets to come in—was 974.” –Marc Topkin, Twitter, April 10.

We’d had snow, and when the night game was rescheduled for 1:10 due to cold, that cinched it. My parents made me get this job—value of hard work and a dollar and other clichés; the job itself was a cliché, grocery checker, and so was my boss. Lengel taught Sunday school and all the rest but when he wasn’t hiding behind the door marked MANAGER he didn’t miss much, unfortunately. I worried he’d already discerned my plan to quit with his cliché beady eyes.

My parents didn’t know about the time change but were unwitting abettors to my crime: they had gone so far as to write a Sammy-is-too-sick-for-school note so I could actually work on a Monday and reimburse them for my ticket. It wasn’t until I finished breakfast that I considered sitting in the stands in this cold, and I felt some of the dread Krakauer suffered when he realized his jet was cruising over Nepal at the same altitude at which he’d soon be climbing Everest. Still, that dread was counterbalanced by another Krakauerian feeling: getting out of my apron and into the wild. I vowed that if I ever worked another cliché job I’d be like Alex Supertramp doing two months in a Bullhead City McDonald’s to finance his Great Alaskan Odyssey. Sure, he died, but he died free.

As I biked to work, I distracted myself from the cold by envisioning the game to come: sitting next to me, I decided, would be two girls, one with pert buckteeth and eyes as black as vest buttons, the other with white skin and flesh-colored hair, like an underdeveloped photograph of a redhead. Both of them pretty and spoiled, summering at the beach and wearing their bikinis right into the grocery store. (Imagine Lengel’s response to that.) I rehearsed retorts to Lengel’s anticipated clichés of disapproval. “You’ll feel this for the rest of your life,” he’d probably say, and I probably would. I practiced a wordless apron-toss of resignation by mimicking Peavy throwing down the rosin bag: a gesture of purposeful contempt.

Which I never got to make, because when I got to the store Stokesie told me Lengel had left in a state: his daughter had had some sort of attack and had to be ambulanced to the hospital. I felt like I’d just had an injection of iron. I opened my register and didn’t say a word until 11:30, when I took off my apron as planned. But I didn’t have the heart to rosin-bag it. All I said was, “Well, I’m going to the game,” and by the time Stokesie said, “In this weather?” I’d already sauntered past the electric eye and through the sliding doors. As I biked through the trafficky city I had the feeling that Lengel’s daughter was with me. The thought of going to the game was intolerable. Instead I turned left and followed the street until it ended at the ice-blue whitecapped lake.

Our house came with rose bushes. We have not done the greatest job caring for them in the years since, which we rationalize away by saying that we prefer a wilder look in our roses, that we don’t want them kempt and orderly. We don’t want roses suitable for grandmother’s tea; we want roses akin to the brambles that try to keep Prince Philip from waking Sleeping Beauty. One result of this benign neglect is that one of the bushes, at the front of the house, began shooting off a horizontal branch or two, making it difficult for us to walk what amounts to a path from our front door into the yard. (It’s not really a path, and the slope makes it even less so. I once took a tumble trying to bring my cat home. I kept possession of the cat all the way to the ground.) Nothing had ever bloomed on that branch until a few days ago, and only then did we realize that the color of the bloom (dark red) did not match the bush (pink) we had believed was the source of this branch. Instead, this was a volunteer offshoot of a nearby climbing rose. Having no trellis or other structure to cling to, it sprays off wildly toward the sidewalk.

In the end, we’re going to have to do something about this branch because at the moment it is a thorny gate preventing me from weedwhacking. But for now, it’s a weird, ungoverned offshoot of something that was once constructed, by human hands, to be the epitome of classical beauty, in the human eyes of a city-dweller. Its resistance to those norms verges on revolution. You simultaneously do and do not want to mess with it. You regret and enjoy its excesses. You wonder “what if I’d spent the last few years taking better care of it?” but do not wonder this in a negative manner, exactly; it is a genuine question in your mind.

And in the end you shrug your shoulders. The past isn’t the point; the future barely is. The present, in its unpredictability and joy and pain, is the point.

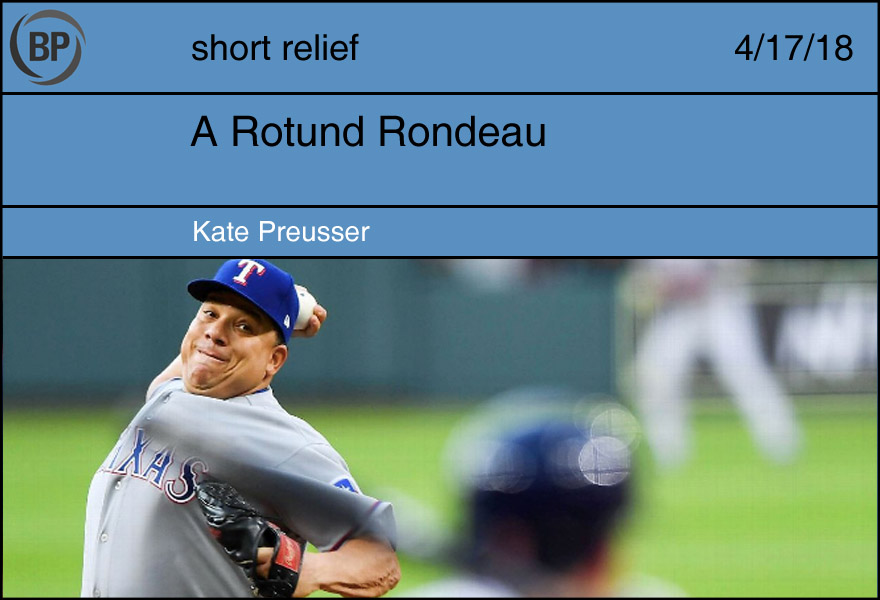

In surely unrelated news, Bartolo Colon got awfully close to a perfect game on Sunday night.

Our Bartolo, age forty-four,

Built like a bow-legged stevedore;

The jowled physique of Fred Flintstone

Mocks fetishizing muscle tone–

This chunky, chuckling lanzador.

Regarded as a dinosaur,

Charming relic of baseball yore.

Then: a perfect game almost thrown

By Bartolo.

Changeup, curve, slider (back door)?

No. Sinker, sinker, then one more,

Relentless dotting of the zone:

No period he, but Colón

Attacking with renewed vigor:

The Bartolo.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now