Exactly 15 years ago today, former Baseball Prospectus writer and mover-on-to-bigger-things Nate Silver published this article about the lack of relationship between player salaries and MLB ticket prices. In the ensuing decade and a half, one of the refrains we hear every year is that it costs too much to go to a ballgame and the reason is all of the money these players are making. This illustrates two points:

- Some controversies never die.

- It was 15 years ago! Time flies when, well, you’re getting really old.

Recent news brought this into focus. The Orioles are offering free tickets to kids for the entire season. Well, it applies only to kids under age 10. And only for upper deck tickets. And the deal requires the purchase of a full-priced adult ticket. But if it sounds like I’m picking on the Orioles, I’m not. The adult ticket, depending on the opponent, costs $18-$39, but if you bring two kids, then that’s only $6-$13 per person. And they’re making every game available, not just April weeknights against Tampa Bay and September weeknights against Oakland. Good for the O’s.

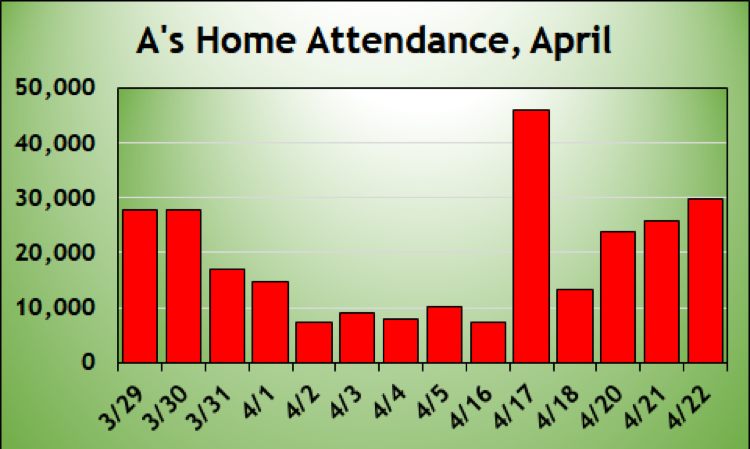

On April 17, the A’s gave away free general admission tickets to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Oakland Coliseum which, as I wrote last week, opened for baseball on April 17, 1968. As a result, here’s a chart of the A’s home attendance this year:

Obviously, when you give away tickets, as the A’s did, or offer them for much less than usual, as the Orioles are effectively doing, you get more people coming to the ballpark. That, in theory at least, expands the fan base. That’s good!

So why don’t teams do it more often? Why does it cost … just randomly going to the Phillies website … $24 to $140 for a seat in the infield for the Phillies-Padres game on July 22? Doesn’t it have something to do with salaries, which average $4.52 million (per USA Today, average of Opening Day salaries) per player?

No, it really doesn’t. The idea that player salaries underpin ticket prices is not supported by economic theory, by the real world, or by how tickets trade. I’m going to explain all three.

Economic Theory

If one of the supermarkets in your town raises its price on bananas by 50 cents per pound, you’ll buy them at another supermarket. If Colgate costs twice as much as Crest, you’ll brush your teeth with Crest. If there are two movie theaters in town, both with stadium seating, and tickets at one are higher than the other, you’ll see the new “Avengers” movie at the cheaper one.

By the same token, if oil prices go up 20 percent, gas stations will, in concert, have to charge more. They’re in a cost-plus business. What they charge is based on what their supplies cost, subject to market forces. Competition, cost of inputs … this is basic market economics.

Of course, basic market economics don’t always apply. It costs a ton of money to build a power plant, so governments grant utilities local monopolies. But in exchange for the local monopolies, governments approve the prices they can charge. The rates you play for your electricity are regulated.

Baseball teams have the best of both worlds. They don’t face competition. That’s partly because they have an antitrust exemption, but mostly because it’s not practical for investors to start a new baseball league that plays in MLB cities. Yes, they compete with concerts and movies and other spectator sports. But if you want to go see live baseball, each team is literally the only game in town. (OK, one of two in the three largest cities in the country.) Nobody’s going to undercut them on price.

But while they’re an effective monopoly, they’re not a regulated monopoly. There is not municipal or regional rate commission that approves ticket prices. They charge whatever they want.

And when you can charge what you want, the watchword is what the market will bear. Given the choice of charging $30 or $20 for a seat, teams realize that they’ll probably sell more seats at the lower price. But they might not maximize profits. The bump in attendance may not offset the foregone revenues per ticket. And more people attending the game means more ushers and ticket sellers and concessions workers and cleaners on duty as well. Teams are going to charge whatever makes them the most money. Player salaries are a fixed expense. They don’t enter into the equation.

The Real World

That’s the theory, at least. But as Silver wrote, “The problem with this line of argument–the problem with a lot of economically-based arguments–is that it’s easy to let the theory get ahead of the data.”

Silver’s analysis was effectively a check on economic theory. Player salaries have indeed risen in aggregate, but they don’t always do so on a team level. I looked at Opening Day payrolls, per Baseball-Reference, for each season in the 30-team era. Here are the 10 greatest annual declines in Opening Day salaries since 1998:

| Team | Prior Year | Current Year | Decline |

| 2013 Marlins | $107,678,000 | $24,761,900 | 77% |

| 2006 Marlins | $60,408,834 | $14,671,500 | 76% |

| 2013 Astros | $37,651,000 | $14,672,300 | 61% |

| 2016 Padres | $125,203,700 | $50,656,166 | 60% |

| 2011 Royals | $73,105,210 | $35,712,000 | 51% |

| 1999 Marlins | $41,864,667 | $21,085,000 | 50% |

| 2012 Astros | $71,110,500 | $37,651,000 | 47% |

| 2004 Rangers | $103,491,667 | $55,050,417 | 47% |

| 2011 Rays | $71,923,471 | $41,053,571 | 43% |

| 2003 Rays | $34,380,000 | $19,630,000 | 43% |

Silver’s research indicated that ticket price changes were uncorrelated to changes in team payrolls. Let’s drill down specifically on the teams that cut payroll, fulfilling the wishes of those who insist that lower player salaries would yield lower ticket prices.

I was able to find data (source: TMR, via statista.com) for average ticket prices for 15 of the 23 teams over the past 20 years that cut payroll by at least a third, ranging from the 2013 Marlins above to the 2012 Red Sox (34 percent). Of the 15:

- Eight reduced ticket prices, by an average of 3.8 percent, ranging from a 1.2 percent cut for the 2013 Marlins (reduced payroll 77 percent) to a 14.4 percent cut for the 2012 Mets (reduced payroll 40 percent).

- Three held prices steady.

- Four raised prices: 2007 Nationals (raised prices 1.1 percent, cut payroll 41 percent), 2015 Brewers (raised prices 5.4 percent, cut payroll 35 percent), 2008 A’s (raised prices 22.3 percent, cut payroll 40 percent), and 2016 Padres (raised prices 44.8 percent, cut payroll 60 percent).

Overall, of the 15 teams that trimmed payroll by at least a third for whom I found average ticket price data, the mean ticket price rose by 2.9 percent. The median declined just 1.2 percent, a far, far cry from the 33 percent-plus payroll reductions.

Silver’s point remains valid. There is no evidence that teams respond to lower player payrolls by meaningfully reducing ticket prices.

How Tickets Trade

I have a niece who lives in Boston. Say I want to bring her to a game at Fenway Park this summer. June 8, Friday night against the White Sox. I don’t get to Boston much, so let’s splurge. Field boxes are $142-$155. Loge boxes are $104-$115. Or maybe a Green Monster ticket! They’re $215-$290. Let’s check the seat map …

No field boxes. No loge boxes along the infield. No Green Monster tickets.

But wait, there’s StubHub. Let me check there. Ah, good. They have field boxes … but they’re $225 and up. Infield loge boxes start around $120. And the Green Monster tickets start at $299. All above face value.

And therein is the problem for teams. When ticket sellers can get more than face value in the secondary market—StubHub, SeatGeek, and their ilk—it means the face value is underpriced. If people are willing to pay $249 for a $155 field box, it doesn’t make any difference whether the price on the original ticket is $155 or $205 or $105 or $5. Somebody’s willing to pay $249 for it, so that’s what it’ll sell for. If the Red Sox cut the price of the ticket by 40 percent, to $93, there will be three effects:

- They’ll reduce their revenues on the ticket by $62.

- They’ll increase the profit that’s split between the person who originally bought the ticket and the reseller by $62.

- They’ll incentivize more of the people who originally bought the ticket for $93 to sell it.

Teams use dynamic pricing, i.e. setting the price based on the opponent and the day of the week (Thursday afternoon games in September against the Padres cost less than Saturday evening games in August against the Yankees) in order to match supply and demand, and capture the money that might otherwise go to resellers. That’s understandable. If somebody’s going to pay $249 for a ticket to a ballgame, it seems fairer for that $249 to go the team instead of to somebody who bought the ticket in order to split a resale profit with StubHub.

So that’s another reason teams won’t cut ticket prices. It’ll help some people. But for lots of teams, and especially for their more attractive games, it means that the consumer will wind up paying the same amount for the ticket, with the money going to resellers and original ticketholders instead of the club. Doesn’t help fans, does hurt the club.

***

Lower ticket prices would be nice. But economic theory says it won’t happen. The example of teams that have cut payroll says it won’t happen. And the modern ticket market, with ubiquitous resellers, says it won’t happen. So don’t blame the players and what they get paid. They have nothing to do with it.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now