My father is nearly done having to work. He belongs to perhaps one of the last generations of peoples to feel he can approach or achieve “retirement age”, and has worked for nearly fifty years, veering through largesse, near-bankruptcy, and everything in between. If you subscribe, as I do, to John Muir’s notion that everything in the universe is hitched together, my dad cannot proclaim himself that American ideal of a “Self-Made Man”, because such a thing is impossible. Still, he’s more self-made than most, and having worked at his side for the past thirteen years I can attest that few people I know have exerted more energy longer at their job, solely for the privilege of quitting it.

I’ve asked him a few times what he wants to do when he retires, and the answer has never been the same twice. Once it was opening a clock repair shop; another time, buying a house by the ocean to watch the storms pass by. Probably the most common response has been a semi-sigh, slouched shoulders, and upturned palms. I don’t think he knows. I don’t think he ever has. Retirement for my father seems to loom not as a well-earned rest, but an awkward and unnatural adornment, like a diamond ring on a giraffe.

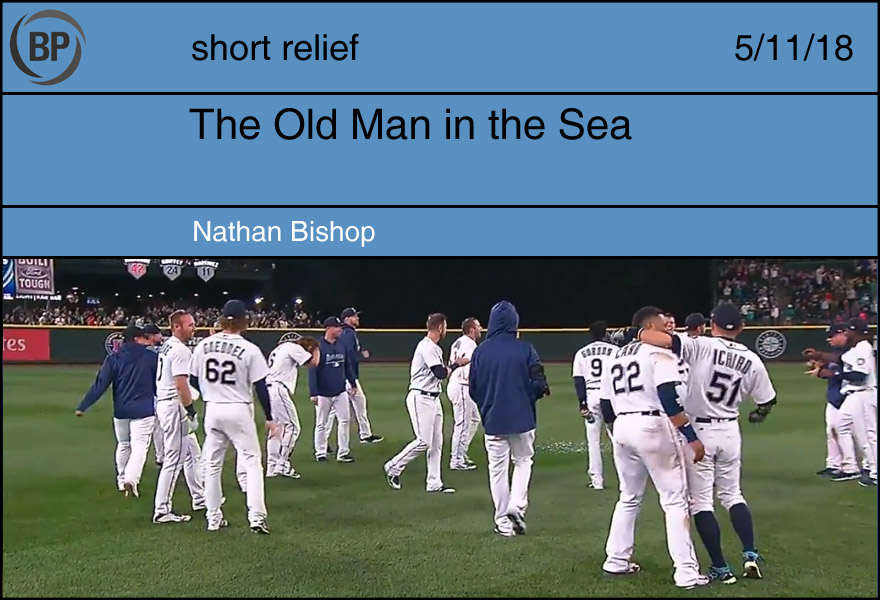

I thought of my dad Wednesday night, as Kyle Seager snared a vicious Josh Donaldson one-hopper, and tossed it to Ryon Healy, and the Mariners poured out of the dugout to celebrate James Paxton’s no-hitter. I thought of him not because of the win (triumph isn’t a thing expected or much experienced in my family), but rather in the aftermath, as joining the Mariners was Ichiro, in full uniform, just days after announcing he wasn’t going to play anymore.

Famously, Ichiro is almost the antithesis of a self-made man. Like Beethoven and Mozart before him, his genius was identified at a young age by his father, and his family entirely reoriented around harnessing that genius. Reading about Ichiro’s upbringing has an element of tragedy baked into its very DNA, and it is a credit to his talent, ethic, and humanity that he seems to keep that tragedy at bay. His career’s story, given the whole, rings largely as a happy one. Still, age’s evils corrupt every man’s bones and his, whether he admits it or not, are no longer able to play major league baseball. It’s time to stop, and if we believe a happy retirement is the byproduct of professional success and hard work, few have earned it more.

Still, there he is, running around with the team, throwing himself into the celebration as though he were still leading off and starting in right field, and wearing the full costume, batting gloves included. He made it clear, rather, he made the GM make it clear, that his new arrangement with the Mariners was specifically NOT retirement. For the man who has a little less than half-joked the only thing waiting for him after baseball was death, the necessity of that specificity feels like an act of survival.

So, for now, Ichiro is done playing baseball, and appears content playing at playing baseball. He is both gone, and very confusingly still present, slowly growing translucent with his first few steps into the cornfield. A few more, and he’ll disappear forever. Retirement isn’t the goal. It’s a threat.

Though baseball, in its lengthy history, has accumulated an astounding number of rules and regulations so that the most minute elements are dictated to the players and fans, much of baseball commentary surrounds its air of mystery. Its origins are murky, its role in American life is murky, and so, too, is its very nature.

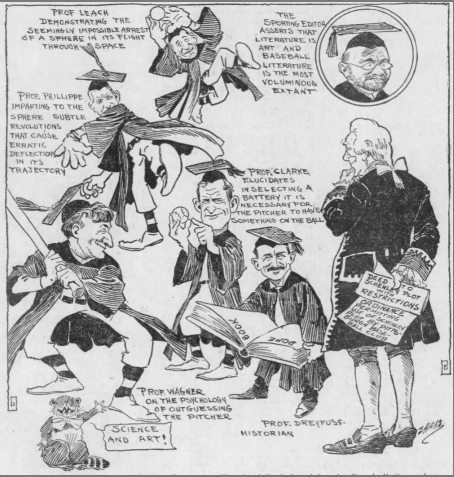

In 1911, the question of baseball’s nature became vital for the Pittsburgh Pirates, who needed to assert that baseball was either a science or an art in order to receive state permission to expand Forbes Field into a piece of unoccupied land that could be used only for state art or science buildings.

The team’s president, Barkey Dreyfuss, claimed baseball a science, declaring the team to have employed very scientific methods of selecting players and determining in-game strategies. Conversely, a number of councilmen believed it impossible to discern baseball’s exact scientific capacity and charged Dreyfuss with being too close to the situation to see baseball in its entirety. After several months of discussion, the council eventually declared baseball to be a science and granted Dreyfuss permission to expand the park.

Though nobody in that particular debate sided with baseball as art, for years surrounding the event, many local and national sportswriters busied themselves with deciding whether baseball could be art. Some contended that baseball and art could not be more different, as the latter is forever while the former is fleeting. Others believed that baseball contained the same beauty as art and was therefore an art. Each successive argument further blurred the lines between science and art, with every component of baseball, from pitching to base running, simultaneously declared science and art, though not by the same people.

While the initial framing of the argument posited baseball could, and likely is, both science and art, the discussion strayed from this premise, pitting science against art and forcing baseball to choose between the two. Of course, the entire history of baseball demonstrates the impossibility of categorizing it as one or the other. Baseball, indeed, is at its best when those observing it remember that rather than scholars and statesmen, sometimes we need to be raccoons.

Wednesday’s game between the Mets and the Reds was sad enough on its own–both teams have been wretched recently–without the debacle in the first inning. Mets manager Mickey Callaway made a critical clerical error by posting the incorrect lineup in the dugout, and as a result the Mets turned a potential two-out rally into an embarrassing goose egg. (Wilmer Flores and Asdrubal Cabrera hit in the wrong spots in the batting order, undoing a Cabrera double and forcing Jay Bruce to add the ol’ “2-unassisted” to his stat line for the season.) The Mets would later go on to lose the game by a single run in extra innings, so if you wanted to say that the manager’s mistake cost the team the game… let’s just say you’d have a case.

If you’re a Mets fan, you’d probably say “oh yeah, that’s a classic Mets move.” If you’re a Reds fan, you’d probably say “I’m surprised it wasn’t us who did that.” Of course, almost exactly 10 years ago, the Reds did that, batting out of turn at the end of an embarrassing 8-3 loss to… the New York Mets.

A day earlier, the Mets and Reds completed a trade involving two very similar players who saw promising careers mangled by injury: Matt Harvey and Devin Mesoraco. Each goes from a situation of little hope to a situation of slightly improved hope; each had a team full of ennui give up on them, but only the slightest sliver of optimism glimmers. The Reds have been one of the worst teams in baseball all season, if not the worst. They’ve been at or near the bottom of the NL Central for years. The Mets have played very poorly recently after a hot start to the season, but seem to be falling into a familiar pattern of injuries and ineffectiveness.

It almost certainly didn’t happen, but I like to imagine a moment where the two freshly-dealt players passed each other in the hallway between clubhouses before Tuesday’s game. Each carries an overstuffed bag of gear, and they make eye contact as they pass each other. Harvey raises his head just slightly and Mesoraco gently dips his chin. They share an unspoken understanding that even when things change, they also stay the same.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now