It started with a heist, pulled off on November 14, 2003.

Minnesota traded 27-year-old catcher A.J. Pierzynski to San Francisco for 28-year-old reliever Joe Nathan and pitching prospects Francisco Liriano and Boof Bonser. Pierzynski spent one miserable season with the Giants, playing poorly and famously kneeing trainer Stan Conte in the groin, at which point they cut their losses by non-tendering him with two years of team control remaining. Stud prospect Joe Mauer replaced Pierzynski behind the plate for the Twins, who won their third of what would be six AL Central titles in nine seasons.

Nathan became the best reliever in Twins history and within two years their rotation included both Bonser and Liriano, the latter of whom was having an all-time great rookie season when his elbow gave out. Before that happened it looked like the trade might go down as one of the most lopsided in MLB history, but Bonser proved to be a replacement-level pitcher and Liriano’s post-surgery career is a wildly inconsistent mix of ups and downs that blend together into mediocrity. Instead, it’s merely the best trade in Twins history.

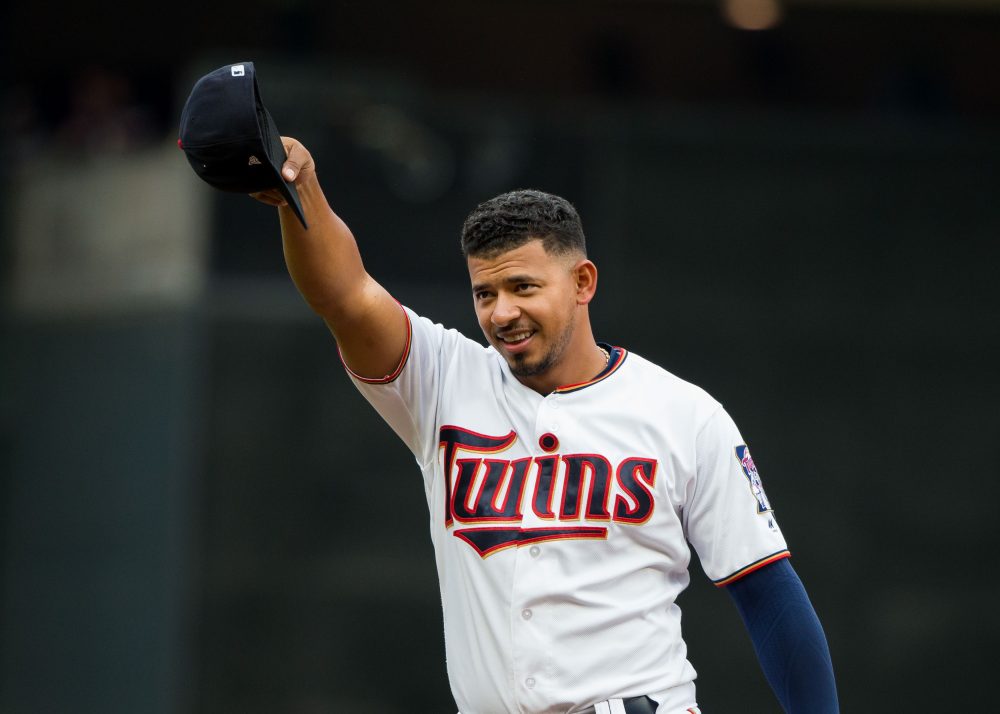

These days Pierzynski is an announcer, Nathan is a guest on my podcast, Mauer is a first baseman, and Terry Ryan is a Phillies scout after being fired as Twins general manager, yet 15 years later the trade is still paying dividends for Minnesota. Liriano had exhausted the Twins’ patience by mid-2012, so with his free agency around the corner they traded him to the White Sox for infielder Eduardo Escobar and left-hander Pedro Hernandez—“minor leaguers” was probably a more accurate description than “prospects.” Or as Ryan explained when asked about the perceived light return for Liriano: “We didn’t want to be left with nothing.”

Hernandez was close to nothing, as the generic soft-tossing lefty logged 66 innings in the majors with a 7.33 ERA. Escobar proved to be very much something, although not at first. Standout defense got him to the majors and seemingly everyone viewed him as a utility man long term. “He doesn’t really profile at third [base] offensively, but he can play there,” Ryan said of Escobar on the day of the trade. “He’s got tremendous energy … defensively you wouldn’t have any problem with any of the three [infield positions].”

Astros special assistant Kevin Goldstein, then writing about the trade for BP, saw Escobar’s best-case scenario as a “second-division shortstop who bats ninth” and called him “an outstanding defender with the ability to provide value with the glove at second base, third base, and shortstop.” Ryan, Goldstein, and everyone else was right about Escobar, at least initially. His defense drew rave reviews at every position, in the minors and the majors, but he just couldn’t hit. Escobar batted .270/.317/.360 in the minors and .228/.280/.307 in 332 plate appearances through his first three seasons in the majors.

In the second half of 2013 the Twins demoted Escobar back to Triple-A, where the switch-hitter showed offensive potential for the first time in his career by hitting .307/.380/.500 in 43 games. He was still just 24, and his development timeline was atypical thanks to the White Sox calling him up at 22 to mostly sit on the bench. However, the Twins were slow to come around to the idea of Escobar as more than a utility man. In fact, the story of Escobar’s now seven-year Twins career has been one of constantly having to convince and re-convince people that he’s deserving of regular playing time, often only getting opportunities as a fallback option.

- 2014: Escobar began the season on the bench, behind starting shortstop Pedro Florimon. Escobar got his first big opportunity when Florimon went 7-for-65 (.108) through mid-May and he took full advantage, batting .275/.315/.406 with 43 extra-base hits in 465 plate appearances … only to see the Twins hand the shortstop job to rookie Danny Santana down the stretch.

- 2015: Escobar began the season on the bench, behind Santana. He got another opportunity when Santana hit .215 and struggled defensively, and Escobar took advantage by batting .262/.309/.445 with 47 extra-base hits in 446 plate appearances.

- 2016: Escobar began the season as the starting shortstop, but lost the job to Eduardo Nunez after a bad first month. He played sparingly in the second half even after Nunez was traded to the Giants—this time the deal worked out just fine for San Francisco—as the Twins turned to rookie Jorge Polanco at shortstop down the stretch.

- 2017: Escobar began the season on the bench, behind Polanco. Ehire Adrianza became the primary backup shortstop, leading to Escobar starting more games at designated hitter (17) than shortstop (12). He got an opportunity in August, at third base, in place of the injured Miguel Sano. Escobar started 42 of the final 43 games, slugging .524 with 11 homers.

- 2018: Escobar was slated to begin the season on the bench, behind Polanco and Sano. In late spring training Polanco was suspended 80 games for performance-enhancing drugs, making Escobar the Opening Day shortstop. He made 14 starts at shortstop and then shifted to third base following another Sano injury. He’s currently hitting .281/.333/.547 to lead the Twins in OPS.

Those are broad strokes, but you get the idea. Just once in five seasons did the Twins plan to have Escobar in the Opening Day lineup, and even then they took the starting job away after a month. Yet time after time he’s waited for an opportunity and then made the most of it, regardless of when, and how, and at which position. Escobar began his Twins career as an above-average shortstop and a below-average hitter. Then he was an average shortstop and an average hitter. And now he’s a below-average shortstop and an above-average hitter.

Those rapidly shifting combinations no doubt played a part in his struggle to secure full-time work, contributing to the skepticism with which his success has been viewed. In particular, it’s been clear for a while now—spanning two managers and two front office regimes—that the Twins no longer see him as a capable shortstop defensively. BP’s fielding metrics share that view, rating Escobar as well below average there in recent years. All of which makes the path he’s taken even more remarkable. Escobar was the epitome of a good-glove, no-hit shortstop, and no one could have envisioned that he’d still be in the majors after the “good glove” part of that skill set vanished.

Escobar has made 273 career starts at shortstop for the Twins and has hit .274/.321/.434 in those games for a .755 OPS that ranks as the highest in team history among all players with at least 150 plate appearances as a shortstop. (Second place belongs to Roy Smalley, at .745.) And while being the best-hitting shortstop in Twins history, the Twins have chosen to bench Escobar in favor of, among others, Pedro Florimon, Danny Santana, Eduardo Nunez, Jorge Polanco, and Ehire Adrianza. His quest for playing time then took him to third base, where he’s become a middle-of-the-order slugger. It’s a helluva thing.

Since the beginning of last season, Escobar has 28 homers and a .471 slugging percentage in 163 games. Dating back to September 1, he ranks among MLB’s top 15 in both homers (16) and slugging percentage (.566), and the only infielders to out-slug him during that time are Jose Ramirez, Francisco Lindor, Nolan Arenado, and Josh Donaldson. His outgoing personality and sense of humor have made #Ed a team leader and a fan favorite, and he even hung out with Nicolas Cage. Over the past 20 years, the only hitters with more seasons in a Twins uniform are Joe Mauer, Justin Morneau, Michael Cuddyer, Torii Hunter, and Jason Kubel.

And yet Escobar’s short- and long-term outlook in Minnesota is still unclear. Sano is nearing a return from the disabled list, Polanco will be back from suspension in late June, and Escobar is an impending free agent at age 29. If the Twins go back to their original plan of Sano at third base and Polanco at shortstop it’s possible that Escobar could spend his final three months in Minnesota as a part-time player, which would be fitting in a sad way. He’s perpetually the backup quarterback who comes off the bench to lead fourth-quarter comeback wins, only to resume holding a clipboard.

Or maybe the Twins’ view of Escobar has finally changed as much as he has. Escobar has always been a free-swinger and has never controlled the strike zone well, leading to some ugly strikeout-to-walk ratios throughout his career. None of that has changed. Grouping his seasons into two-year periods to eliminate some sample-size issues that come from part-time play, his swing rate on out-of-zone pitches is nearly unchanged from 2013-2014 (38 percent) to 2015-2016 (36 percent) to 2017-2018 (37 percent). His walk and strikeout rates are also pretty stable.

However, that lack of plate discipline isn’t as big of an issue when it’s attached to a swing intended to do damage when it connects, and that’s the biggest change for Escobar. He’s made a concerted effort to put the ball in the air, tailoring his approach from both sides of the plate to elevate the ball with authority, and he’s done it without sacrificing a ton of contact. That’s produced more fly balls and more extra-base hits, along with a lower batting average on balls in play (fly balls are converted into outs more often than ground balls, so that’s to be expected).

| Two-Year Period | FB% | ISO | BABIP |

| 2013-2014 | 35% | .125 | .320 |

| 2015-2016 | 38% | .146 | .291 |

| 2017-2018 | 46% | .213 | .284 |

His yearly average launch angle also tells that same story, perhaps even more clearly.

| Year | Launch | Rank |

| 2015 | 13.5 | 59 of 234 |

| 2016 | 15.0 | 46 of 225 |

| 2017 | 17.5 | 24 of 237 |

| 2018 | 21.8 | 7 of 204 |

He’s basically moved up one rung on the launch-angle ladder each season. So far this year Escobar has the second-highest average launch angle in the American League, behind only all-or-nothing slugger Joey Gallo. Escobar has always been an ultra-aggressive and at times even undisciplined hitter, but now those aggressive cuts are better designed for doubles and homers rather than singles and doubles. Step by step, the 5-foot-10 former slick-fielding utility man has turned himself into a power hitter. And thanks to the trade tree sprouting another branch and Escobar’s evolution as a hitter, the Twins’ heist on November 14, 2003 has turned into a long con too.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now