For the first couple of weeks, he tries to learn everyone’s names, from the trio of outfielders who all look alike, young and tanned and hungry, to the seemingly unending stream of guys coming out of the bullpen, a clown car unloading. So many he sorts them into two groups: Beard and No Beard, and works from there. But then the season starts in earnest, and the bullpen guys are getting called up and sent down and spot starters parachute in to spend a night or two on the team before returning to whatever corner of America they play in, new faces in and out all the time and eventually he decides: enough, and stops trying. He worries this will make him seem standoffish or indifferent, but if anything, the younger players seem to redouble their admiration for him; one even calls him “Mr. Werth.”

He hasn’t had more than a couple dozen rehab appearances in the minors since the Twin Towers fell, before the smartphones everyone carries in their pants pockets now; he’s old enough to think of them as smartphones. There were no TV feeds of the minors then, no .gifs to post on the still-nascent internet, which you connected to with a modem, waited patiently for things to load. The minors were once a place you could go to play in benevolent obscurity, get your head on straight, make mistakes only a few hundred people at a time could see. He is both flattered and a little terrified the first time someone presents his rookie card for him to sign at an opposing ballpark; someone planned for him. It’s innocuous, pleasant, even, as the gentleman goes on at some length about the walk-off homer in the NLDS, calls it one of his favorite moments in baseball. Fans can get so close in the minors. That’s something he’s forgotten, or maybe they just felt further away when he was just another name on a jersey.

This interaction is pleasant, but he knows it could be otherwise.

A few weeks later, it is. It’s an away doubleheader, which means double the drunks; beer is cheaper in the minors, that’s another thing he’s forgotten. The PA system plays annoying music for opposing walk-up songs, teenybopper stuff that was popular the last time he was in the minors, boy bands with gelled-up hair who want it that way. “Old school,” the guys in the dugout call it, and then duck their heads, look at him guiltily. The music annoys him more than it should. The league seems small because it insists on acting small.

There is one particularly loud, particularly drunk fan who is heckling all the players. Most of them he doesn’t recognize, so sticks to jabs about poor play, home runs surrendered. “THE SCOUTS ARE WATCHING,” he bellows, and Jayson wants to turn to him and say, they most assuredly are not. But he recognizes the name Jayson Werth, and he has a bag of heckles ready. Someone has again planned for him.

It starts off innocently enough, jabs about his batting average, his age. “You’re so old you have Werther’s Originals in your purse.” Then again, louder, in case he didn’t get it. “WERTH-er’s Originals, get it?” But over the course of the two games, things get louder, and meaner. He goes hitless in the first game, and hears about it over the course of the second. You can’t let hecklers get to you; Jayson knows this. You have to tune out the noise. He’s done it everywhere he’s been. But this man’s voice booms around the near-empty ballpark. It is impossible to ignore. He finds himself pressing at the plate, wanting to get a hit, to shut the man up. He imagines himself knocking one out, then turning around and smirking. He can’t say anything, he knows–he doesn’t want to be someone’s Facebook status. But just a look, maybe as he crosses home plate. He strikes out. He flies out.

The third time he comes up, he closes his eyes for a second in the on-deck circle, takes a breath. Tries to find the boy who stood here almost twenty years ago, in Bowie, Delmarva, Frederick, the one whose jersey didn’t mean anything to anyone except the person wearing it. He brings back the quiet of overnight bus rides, the crack of the bat in a near-empty ballpark. He pictures himself in that empty ballpark. He steps to the plate.

He hits a solid line-drive single, opposite field. For tonight, it’s enough.

The thing about the play is that every aspect of it was perfect.

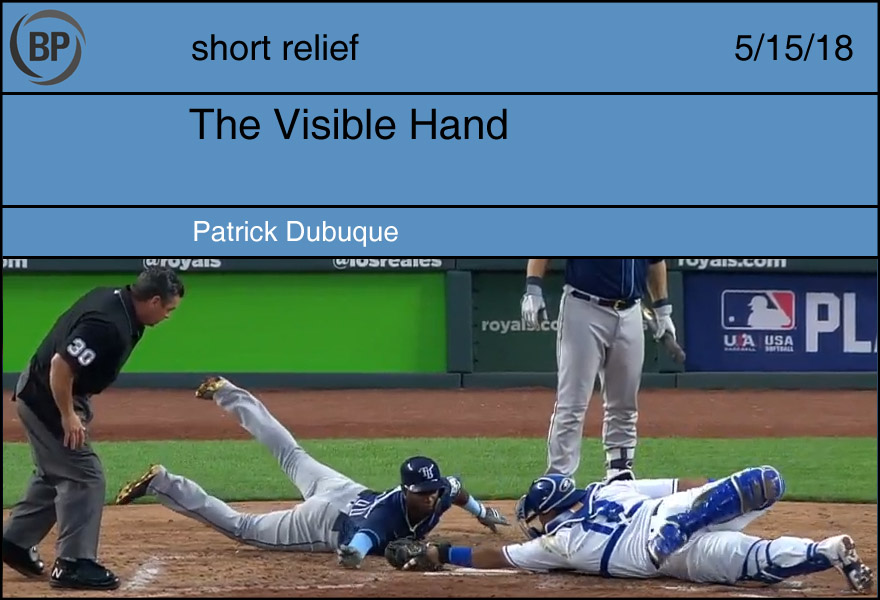

The swing, by Matt Duffy, a timely riposte: a slashing backhand that snapped the ball into right field, sharp and true. The grab, by Soler, in mid-stride: the slightest pause, hammer cocked back, and then a perfect return fired, on one hop, two steps up the line. Salvador Perez, positioning himself perfectly just off the basepath, ready, the tag down. And Adeiny Hechavarria rushing in, as if shoved by God, limbs broken like a game of QWOP. It was a moment where something was meant to be disproven.

The Rays won by a score of 2-1.

It wasn’t long ago, when televisions and reality were only standard definition, that the tag felt like a largely symbolic thing: the runner competed against the throw. In a sport where the vast majority of its witnesses were hundreds of feet away, to see the ball arrive in time and a safe call result would seem like chaos. The truth was whatever it appeared to be.

The advancement of television and replay in baseball has brought with it many crimes: commercial breaks, chyrons, the vertical column around the bag. It has created a level of precision the game itself, in its ancient wisdom, could not anticipate, like a science that asks more than it can answer. But now those twenty thousand in the stands are in the minority; we lucky many behind the camera deserve the truth. And so the tag, the lone intended point of contact between opponents in all of baseball, has become the sport’s most joyously aesthetic moment.

There’s something of childhood here: wiffleball and Little League, where groundballs weren’t so perfunctory, baserunning less advised, rundowns a fifty-fifty proposition. That feeling of tagging a runner, or, more rarely, escaping the near death of the tag, were visceral things. In that moment, there is one truth, and two people.

And that leaves the final perfect moment, one belonging to the televisions: Hechevarria and Perez, both on their stomachs, arms outstretched, staring at each other like gunfighters, the catcher’s outstretched mitt just perfectly aligned between runner and plate, as if the game were designed that way. It was an entire sport enhanced into a three foot radius, with every speck of the dirt surrounding them in 1080p. Hechavarria feints with his right and sneaks the left hand in. It’s a beautiful play. We’re lucky to have seen it.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now