This past Saturday, the Rays tried something new. Prior to their game against the Angels, they announced that career reliever Sergio Romo would be starting the game and pitching an inning or so before ceding the bump to rookie “starter” Ryan Yarbrough for the next several innings. After winning their tilt against the Halos that day, the Rays doubled down and ran Romo out for the “start” on Sunday as well, having him open the game before Matt Andriese took over in the second inning.

The Rays ended up splitting the two weekend games, winning the first but falling in the second. Regardless of the outcome, the decision to upend the traditional protocol of letting one “starting” pitcher go as long as possible before allowing the bullpen to come in has caused a tremendous amount of discussion. But while the Rays’ strategy might be considered novel to many, it’s actually a subject that has come up a number of times over the last few decades (at least).

For instance, during the 1990 NLCS, Pirates manager Jim Leyland started Game 6 with reliever Ted Power, who went 2 1/3 innings before swapping to usual starter Zane Smith. Others have advocated for or against the idea in different forms on and off in the public sphere, most of the time thinking that they were the first genius to come up with the idea out of whole cloth. I should know. In 2013, I published an article at Beyond the Box Score coining the term “opener” for a new relief role in which a pitcher would come in and regularly start games for a host of different tactical or psychological reasons.

It was well received enough that I was invited onto MLB Network to talk to Brian Kenny about the subject, and over the years I’ve posted various other musings on the topic. I’ve never been certain this strategy would be a hugely effective one, but have always hoped that some team would try it out and we’d get to see how it worked in real time. Thanks to this weekend, we kind of could. So let’s try to sort out if this move “worked” for the Rays and in which ways, at least as well as we can given the extremely small sample of two games.

(Before we dig in: I think it’s important to call attention to the fact that there’s a substantial difference in the strategy of the “opener” (start the game with a reliever, then leverage a starter for most of the rest of the game) and “bullpenning” (a term used when no pitcher goes particularly long in a game). The Rays have been throwing the latter of those, sometimes called “bullpen games,” on and off for the last couple years. Sunday’s start falls more into that category than the “opener” category, but we’re kind of lumping it in here because Romo started both of them.)

In my study of the “opener” hypothesis, I’ve found several compelling reasons why a team might want to try a reliever at the beginning of a game. I’ll walk through a few of them and see if Romo’s usage proves some measure of success or failure in each area.

The First Inning is the Highest-Scoring Inning

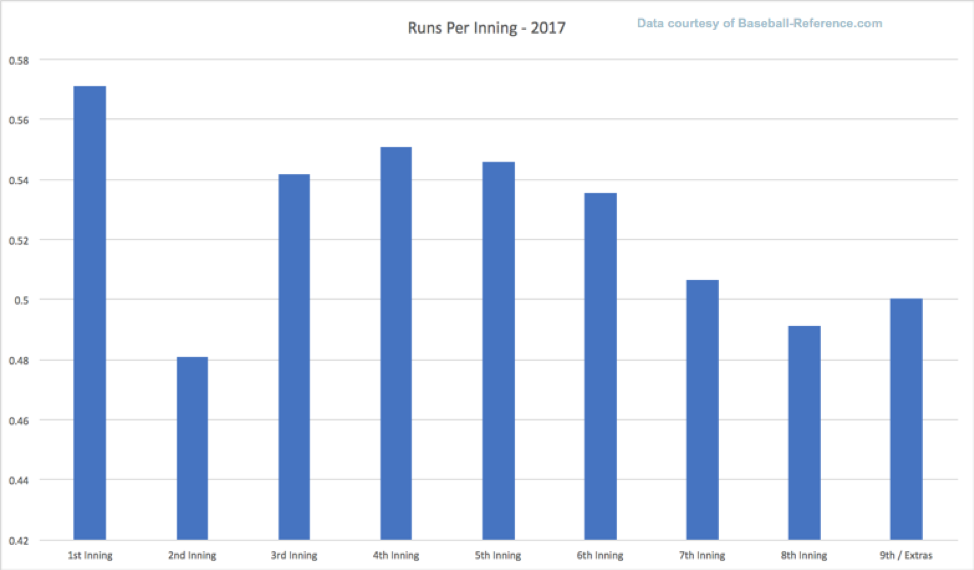

More runs are scored in the first inning than in any other inning. I tried to do something in graphical form during my last ode to the opener, but I think this is a better representation of the difference in inning-by-inning run scoring:

Doesn’t that mean a team might try to put their best pitchers in the phase of the game where there’s more risk of the other team scoring more runs? Of course there’s the possibility some noise is baked in here due to pitchers who “don’t have it” on a given day, but there’s still a likelihood that fresh hitters coming off batting practice, ready to hit, and deemed good enough to bat atop the lineup are going to be more successful to start a game. Instead of putting in a less-than-ideal starting pitcher, try the pitcher who’s more likely to get outs early.

What happened when the Rays tried this with Romo? On Saturday, the opposing team scored zero runs in the first inning. On Sunday, the opposing team scored zero runs in the first inning. Romo was about as effective as anyone could ask for, striking out the side in his first start and only allowing a walk and stolen base in his second. Would Ryan Yarbrough or Anthony Banda have done the same? Maybe! But from a results standpoint, Romo got out of the toughest inning in the game unscathed.

A Good Start Means Better Results Later

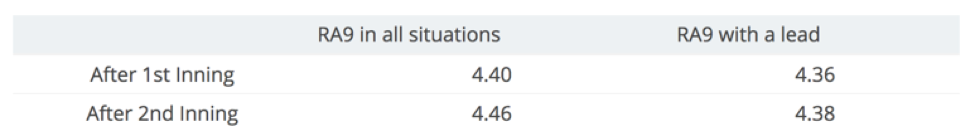

I’ve heard Old Baseball Wisdom that when a team gets off to a good start, it allows everyone on that team to relax and be more effective. I’m not simply talking about “pitching to the score,” but rather the thought that leading early brings good results later. Mindset matters. Well, BP’s Rob McQuown ran the data on 10 seasons (2007-2016), and found that an early lead in the first or second inning tends to very slightly reduce the number of runs allowed in the future by the leading team.

Theoretically, playing well at the start of a game leads to better pitching performance near the end of a game. While on Sunday the Rays didn’t take an early lead until the third inning, Saturday’s game saw the Rays go up 4-0 in the second inning. Later on, Yarbrough would give up a run and Ryne Stanek would give up two more, adding up to three runs allowed in seven innings, or a 3.86 RA9. It’s far too small a sample to ascribe any real meaning to this particular instance, but I think most teams would love to get that RA9 performance out of Yarbrough, Stanek, Chaz Roe, and Alex Colome.

(Sort of) Mitigate the Times-Through-The-Order Penalty

By now we’ve all heard that the more times hitters see the same opposing pitcher, the more effective they become at creating runs. We also know that the best hitters in a lineup tend to congregate at the top. If you bring in the pitcher who’s destined to throw the most innings after a few of the better hitters in the order have already taken their first cuts, you make it so that your longest-serving pitcher sees inferior hitters first during their second, third, and fourth times through the lineup.

On Saturday, Romo faced Zack Cozart, Mike Trout, and Justin Upton. Trout and Upton are two incredible hitters, and Cozart ain’t chopped liver. When Yarbrough entered the game in the second inning, he started his day facing Albert Pujols, Andrelton Simmons, and Ian Kinsler. Quite a bit less imposing. Yarbrough went on to face Trout just twice despite pitching into the eighth inning. Yarbrough also never had to face the top of the Angels’ lineup a third time, and by the time the ninth inning rolled around Rays manager Kevin Cash could call on his best non-Romo relievers to try to eliminate Cozart, Trout, and Upton to end the game.

Of course, Cash called on Ryne Stanek to do this, which ended up in two hard-hit balls, a quick hook, and a closer final score than what was intended. Would the Rays like to have had Romo there at the end of the game to wipe out the top of the Angels’ lineup? Sure. But they already got to use him against those same hitters in a tie game, it just happened to be a couple hours earlier.

Ruin Platoons and Force Opposing Managers to Make Mistakes

Much has been made about the Angels being an ideal opponent when using this strategy. They’re extremely limited in left-handed hitting options and Romo is very good against right-handed batters. Saturday’s game would have seen Yarbrough (a lefty) faced with a tough platoon task ahead of him. However, in my opinion a right-handed lineup is decidedly not an ideal situation for an opener, as the tactic can be used to force the manager to choose between stacking the lineup against the “opener” early or against the long man later. The Angels really had no choice, as their best lineup consists of right-handed hitters almost regardless of the pitcher they face.

There is a caveat here, and his name is Mike Scioscia. Scioscia tends to be one of the more traditional in-game managers, and I’d guess one of the guys least likely to adapt on the fly when faced with a new and outrageous tactic such as the one the Rays employed. If he had a more balanced lineup, might he have committed to more left-handed batters early in the game to offset Romo’s “start”? Would he have gone to pinch-hitters early, or perhaps left them on the bench to rot? We don’t really know, as these games were mostly paint-by-numbers from a tactical countermove perspective.

Get the Most Out of Your Better (But Not Best) Relievers

Conventional wisdom says relievers thrive in dedicated roles, and this absolutely makes sense. “The seventh-inning guy” can prepare in roughly the same way a starter can: go through a routine, set expectations, and have the game meet them more or less. And if a team commits to a dedicated “opener” role for all or most of a season, you can do the same thing. Your “opener” knows what he’ll do—go an inning or two, and attack the best hitters an opposing team has to offer. Your “long guy” still can prepare as if he were the day’s starter and get loose, but maybe just start his routine half an hour later. And there’s no worry about getting one of the two guys up in the bullpen just to have them sit back down and wait for “the right moment” late in the game. With at least these pitchers, you can mitigate the problem of throwing countless bullpen pitches to perhaps never get used.

As the Rays proved by using Romo on back-to-back days, this strategy could allow you to leverage one of your better relievers two or three games out of five. Now we’re talking about taking a good reliever and getting him close to 100-110 innings per season instead of 70-80, all in a way that could mitigate risks of overuse by keeping to a strong schedule and limiting unused bullpen sessions.

Using guys like Josh Hader and Andrew Miller in this kind of opener role is appealing, but I think there’s an argument to be made that you should always keep your best reliever in reserve for high-leverage, close-and-late situations. (But not save situations.) By keeping your most effective guy (or two) in the manager’s back pocket for when he needs them, you might be able to have the best of both worlds. I don’t think you can argue that Romo is the Rays’ best reliever, but they don’t have a particularly strong or deep relief corps.

Play to Your Strengths

The teams best suited for leveraging an opener have a deep bullpen and a weak/young rotation. For that reason, I thought the Rays were kind of an odd fit for this strategy, mostly because they don’t have a particularly strong ‘pen. (The rotation, of course, is sketchy too.) As mentioned above, in an ideal situation the team using the opener should have enough relief options that they’re not throwing a scrub into the first inning to face a team’s toughest foes, but also not leaving zero help in the bullpen for when they need it at the end of a game. In 2018, teams like the Rangers or the Orioles are prime “opener” candidates. They’ve got poorer rotations and deeper bullpens than the Rays might.

***

I also think there are a few issues specific to the Tampa Bay roster and implementation of the methodology we saw this weekend.

Anti-Angels Strategy

Some people (and some teams) might take issue with the fact that the Rays aren’t deploying this opener strategy in some over-arching way across a full season. Instead, this seemed to be designed particularly to take advantage of the Angels. For better or for worse, when one team upends the established dynamic to attack one specific team, that makes the strategy feel less like a grand experiment and more like, well, something of a sneak attack.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s some merit to using the opener strategy tactically rather than making it a full-season experiment, but it harpoons some of the advantages of the system. However, deploying unorthodox strategies infrequently makes them feel like they’re assaults on a particular team or, worse, a particular player. Hitters used to (and still might) get frustrated by shifts, and this is a different but more extreme example. Frustrating an opposing team might be a weird psyops tactic that’s beyond the scope of this article, or it could just feel like poor sportsmanship.

Irregularity Can Be the Enemy

The Rays also worked Romo back-to-back days in this strategy, which could lead to other sorts of problems. An extra (scheduled) day of rest for a reliever could be an ancillary benefit from an opener strategy, but instead they set things up so that a third game in a row could have meant Romo was completely unavailable. (Especially if he pitched longer than expected on the second day.)

Pitchers Pay the Price

There’s another argument against the Rays as a franchise using the “opener” strategy: one could see how using pitchers in new roles and for limited innings that removes the ability to earn statistical benchmarks like “wins” or “saves” may hamper their ability to earn money in salary arbitration. The Rays have a recent history of being extremely cost-averse, and working hard to keep player payroll extremely low in spite of large payouts from the league. We probably can’t (at this point) trust that the Rays are making moves simply in order to win games. They’re probably also trying to drive down salaries and cut payroll. Bill Baer of Hardball Talk covered this angle very well. Suffice it to say, the arbitration system in baseball is mostly broken, and I hope this doesn’t end up affecting Ryan Yarbrough’s future earnings.

***

We need a lot more data to determine if the strategy is a winning one. The Rays winning their true “opener” game and losing a “bullpenning” game the next day doesn’t tell us much. Romo (and Yarbrough!) pitching well in a victory doesn’t tell us much. It’s only through repeated use in different situations and careful criticism that we’ll determine whether this is an effective strategy.

I’m also not immune to the thought that using a pitcher in this role takes something away from the game. I like complete games! I like games with fewer pitching changes! I like 200-inning starting pitchers! So I can see why people may have that initial reaction to reject this as “not baseball.” At the same time, baseball is changing and moving away from those things with or without teams like the Rays trying “openers” or “bullpenning” or anything else. Maybe the change is irreversible, maybe it’s not. I’m excited to see what comes next, just so long as we don’t forget the human cost on both fans who watch the game and players making their fair share of the revenue.

(Hat tips to Matt Gatjka and Andrew Ritter of PiratesProspects.com for making me aware of Leyland’s playoff game version of the strategy.)

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now