He spit, near his shoes. Here we go again.

The ball came flying back from right field, bouncing a few times to hit the cutoff man before landing back in that spot of loose leather underneath his cushioned thumb.

Next up was Pinky Higgins. Years later, Higgins would stand in the Fenway park home dugout wearing the uniform of a manager wondering what had happened to the country he once knew save for those final few men in the office signing checks, men who at least had the damn sense not to follow what had started in Brooklyn all those years ago. But when Higgins walked up to bat that day those years were yet to come, and Bob Harris was pitching in his final season for a doomed Philadelphia Athletics team, in a year of the game that almost didn’t happen, save for a letter from the President of the United States. There were two letters that year.

He wiped his brow and he threw his leg up in the air and tossed his right arm up and over his head with a fastball, down and away. It missed by three inches. Here we go again, he thought again. Twisting the ball, hands behind his back, he realized his best chance was to change where the seams touched his fingers. Two seams. Finger to thumb. When it left his hand it made contact with Higgins’ bat and it flew into the gap in right field, scoring the man who had stood on second.

Higgins was later caught stealing for the first out of the inning, but like the victory, history seems to have declared over his ideas; it wasn’t total. All too often we confuse a single out for a double play, forgetting what led to the jam in the first place, a mistake easily repeated in the following inning and the one after that. With an RBI and an out, Higgins had given the Tigers the only run they would need that afternoon. They went on to beat the A’s with a score of 3-0.

In the end, none of this would matter. The Tigers and Athletics both fared rather miserably that year, but despite the fact that baseball almost didn’t happen, this play did, and it happened under the watchful eyes of 5,103 fans in addition to the countless more tuning into highlights on WIBG and WXYZ. The next day, the United States opened an airstrike onto the Japanese controlled island of Midway, and the reports that something unthinkable was happening in Europe were less than 48 hours off the wire. For some reason, they played baseball again, the very next day.

Last night, the Detroit Tigers played game two of a four-game series against the very same Athletics ball club—for some reason, they will play baseball again, this very evening.

Recently, cameras caught Phillies outfielder Rhys Hoskins jawing at a heckler during a frustrating night at the plate. Because this game took place in Philadelphia and was against the Yankees, who’d brought an invasive species of fan into Citizens Bank Park, chances are the fan deserved it. But Hoskins apologized anyway because that’s what you do.

However, in acknowledgement of all the hecklers deserving to be yelled at, we’ve generated some angry catch phrases for MLB players to use when their goats are gotten:

Hoskins: You want a Rhys of me?!

Buster Posey: I’m Buster. You’re the Bustee.

Nolan Arenado: Buddy, are you one of my teammates? Because I am going to scream at you.

Kris Bryant: There’s nothing I learned in a batting cage that can’t also be applied to a human skull.

Odubel Herrera: I am about to FLIP OUT.

Bryce Harper: Buddy, I’m gonna wash your hair.

Manny Machado: I’m ready to sign a deal: My fist, your brain.

Mike Trout: You will never see me coming. Because no one watches me play.

Mookie Betts: A good Betts? That’d be you getting pounded, friend.

Aaron Judge: I sentence you to shut up, please

- You are a mistrial of humanity

- I’ll be in my chambers…AFTER KILLING YOU

Jose Altuve: Just wait until the other half of me gets here.

Giancarlo Stanton: I am just 10 or 12 straight strikeouts from four or five straight home runs; you’ll see.

Alex Bregman: I’ll put you where I put my mustache between innings: down the drain.

Max Scherzer: I’m a machine built for ass-kicking. And you are a giant ass.

Gabe Kapler: This knuckle sammich is certified organic.

Darren O’Day: I’m “Darren” you to call another balk.

Joey Votto: My full name is Votto-matic Killing Machine.

Freddie Freeman: Sure, I’m the MVP: The Most Violent Puncher.

Yasiel Puig: I may be naked, but you’re about to be afraid.

Franmil Reyes: You like that tattoo? Here, check out the one on my fist.

Johnny Cueto: My next hat shows how you die.

Ozzie Albies: [Instead of calling shot, turns around and points at a fan’s nose before punching it]

Curtis Granderson: They couldn’t find the baseball. Sometimes, people just disappear, too.

Anthony Rizzo: [doesn’t say anything, just slides into your knee out of nowhere]

Joe Maddon: And that’s when the attack comes, not from the front, but from the side—the other two Rizzos … you didn’t even know were there.

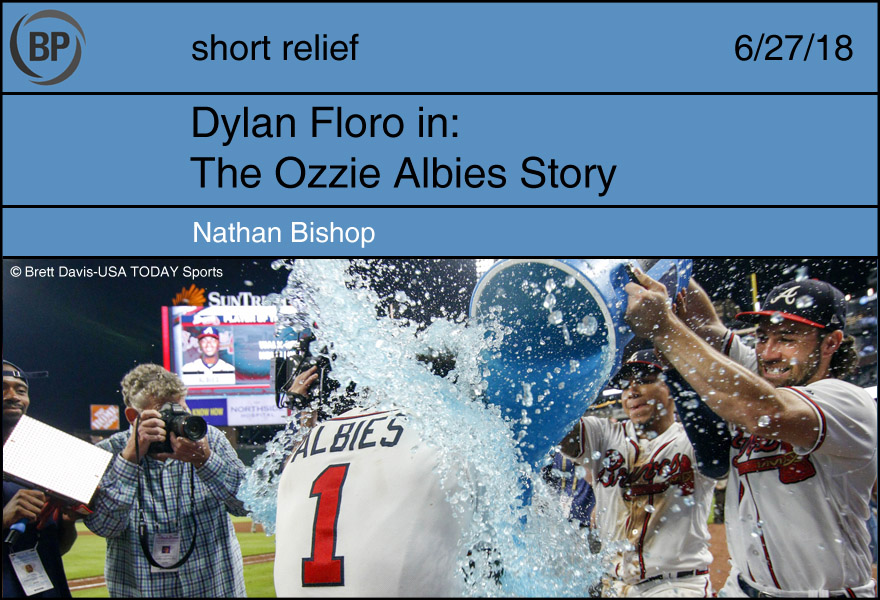

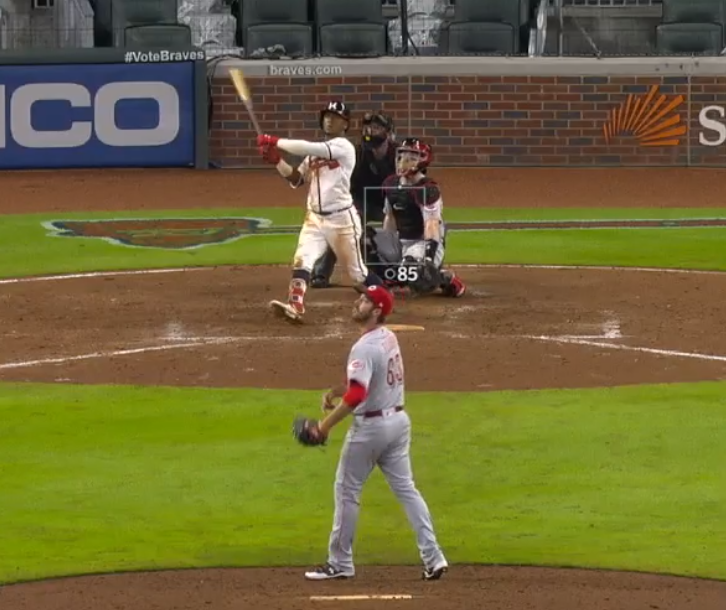

On Monday night in Atlanta, Ozzie Albies, avatar for everyone involved in an 11-inning June baseball game with an 80-minute rain delay, informed a teammate it was time to go home and then promptly hit the home run that allowed everyone to do exactly that. It was a memorable moment, and, huddled with my coffee in the early morning quiet the next day, I found myself watching and re-watching it. Walk-off home runs are not common in baseball, but they are not particularly uncommon either. Someone is always a hero somewhere. Yet, there was something about this one that stuck with me. It was the man who threw the ball Albies hit that captured my imagination. A man named Dylan Floro.

If we insist, as the vast preponderance of insufferable sportswriters and I often do, that baseball serve as a vehicle through which to identify ourselves, to graft our experience upon, then Dylan Floro is an ideal everyman. Drafted in the 20th round out of high school by the Rays, Floro did what most of us are taught to do: He went to college to better his prospects in the workplace. His reward for his academic pursuits? He was drafted in the 13th round by … the Rays. Our efforts so often yield little reward, it seems.

Floro is not a bad major-league relief pitcher. He has a 3.00 ERA in 30 innings this year. Teammate Amir Garrett says Floro has a “really, really, really good” two-seam fastball. Yet he is not particularly good, either. His fastball rarely exceeds 93 MPH, a pedestrian speed in today’s game. He is, fairly simply, the kind of pitcher even a moribund franchise like the Reds allows to sit on the bench until after an 80-minute rain delay, and then until the bottom of the 11th inning. He, like many of us, myself included, is here because there was space for him, and he was easily attained.

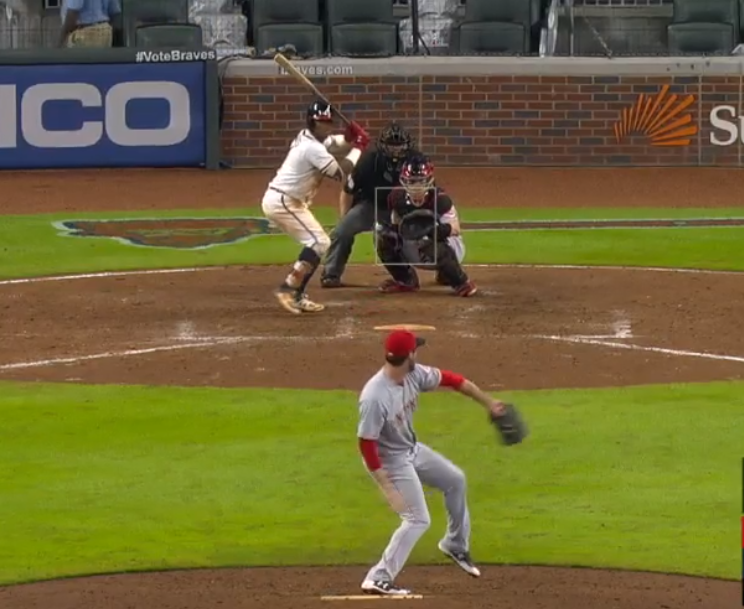

His job Monday night was to get the Reds to the 12th inning, and it took him exactly one pitch to fail at that task. His intent was sound. Knowing Albies swings at the first pitch nearly half the time, the idea was to throw a changeup low and away, and produce a groundball:

It’s important, prior to viewing the next image, to note that while Floro does fail to throw the ball where he wants, he does not fail by much. Additionally, he fails down, which is the baseball pitcher’s recommended direction of failure.

It doesn’t matter, because Ozzie Albies is 21 years old and built entirely of twitchy muscle. He had decided before the at bat he was going to hit a home run, and he is one of the 0.01% of human beings that are capable of both that thought-process and its execution. Dylan Floro was just a prop, a set piece, an actor hired to play a baseball player in a Gatorade commercial starring someone else.

He did his best.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now